Hereditary is a harrowing cinematic experience. Director Ari Aster’s film revels in the off-putting and positively thrives as it builds to hard-to-watch sequences that are bound to devastate viewers. It’s exquisitely crafted and only feels all the more personal because it is so heavily rooted in themes of family, legacy, and guilt.

Upon release this past weekend, the film was hailed as a masterpiece by many a critic and genre fan alike. General audiences, however, have not been so receptive. The film’s CinemaScore came back as a D+ and the buzz from the average viewer has ranged from lukewarm to hateful. So why is a film that has been praised by filmmakers and aficionados being viewed as a disappointment by general audiences? To dig into that, we need to talk about what we talk about when we talk about horror movies.

The concept of a film being ‘scary’ is more than a bit subjective. Each individual audience member is going to have their own personal definition of what is scary and what is not, which is why labeling a horror film as a ‘scary movie’ has been a bit tone deaf from the get-go. Horror is a genre that aims to create a more visceral and violating cinematic experience. As a result of this, well-made films of this genre tend to truly have an effect on audiences. Whether or not they are ‘scary’, via the modern definition, is kind of irrelevant. The classics of the genre, such as James Whale’s Frankenstein or William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, are remembered for the impression they left on viewers even decades later. They were well-made films that told stories of the macabre and dared to push into territory that made audiences uncomfortable. They also left audiences with a great deal to ponder. For a great many years, a horror film’s successfulness was defined by these attributes.

Which is where the discrepancy comes into play. The horror genre’s primary audience always has been and always will be the coveted 18-to-25 demographic. So it’s fair to say that the vast majority of audiences who turned up for Hereditary this past weekend were born between the years of 1993 and 2000. Which means most of them were raised on a diet of mid-2000’s horror films. But here’s the thing: horror films in the mid-2000s were kind of awful.

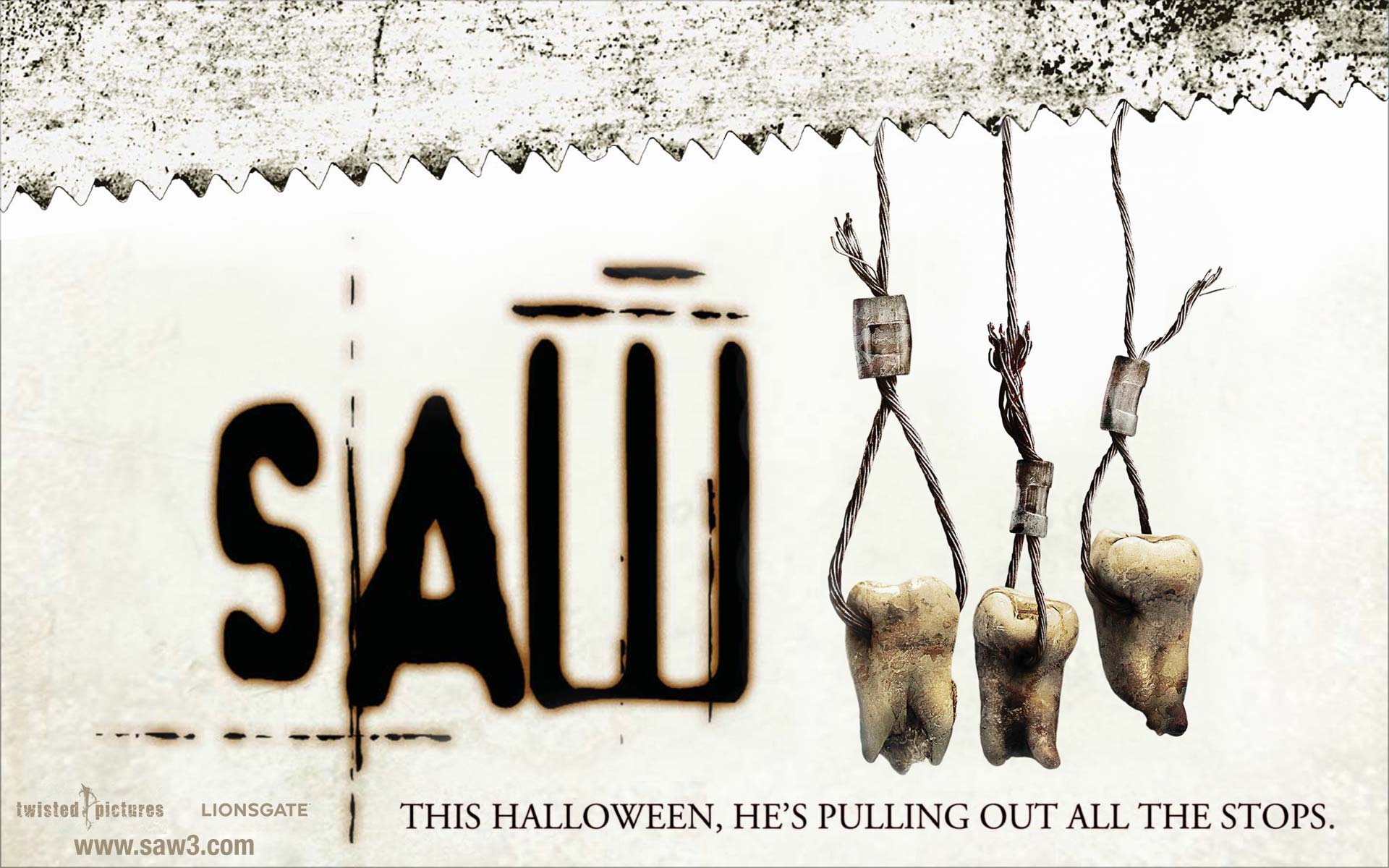

Gone were the thought-provoking premises or the dedication to craftsmanship. In their place was an unhealthy infatuation with jump scares, over-the-top gore, and downright lazy and amateurish filmmaking. For frame of reference, the highest grossing horror film of 2006(the year ’93 babies entered teenager-dom) was Saw III. So to this generation, of fans the term ‘scary’ became much more associated with shock. If a horror film could startle audiences with jump scares, then it was deemed scary.

And as a certain maestro of the horror genre once said, there is a distinct difference between suspense and surprise.

“We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let’s suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, ‘Boom!’ There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: ‘You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!'”

As Hitchcock goes on to state, the first scenario gives the audience fifteen seconds of substance at the moment of the explosion. The second scenario turns the exact same event into fifteen minutes of substance. This is the fault line upon which the horror filmmakers of the late ’90s and 2000s fractured. To many, surprise became far more of a priority than suspense.

The simplest and most obvious manifestation of this change in mentality is the jump scare. Which is precisely what Hitchcock is speaking of in his bomb discussion; the surprise of the bomb is a jump scare. It startles the audience, generating a quick and easy reaction. Horror filmmakers of the late ‘90s and 2000s did not pioneer this tool, it has been a prescient part of film vernacular going as far back as the Lumière brothers. But the films of this era certainly did drive it into the ground.

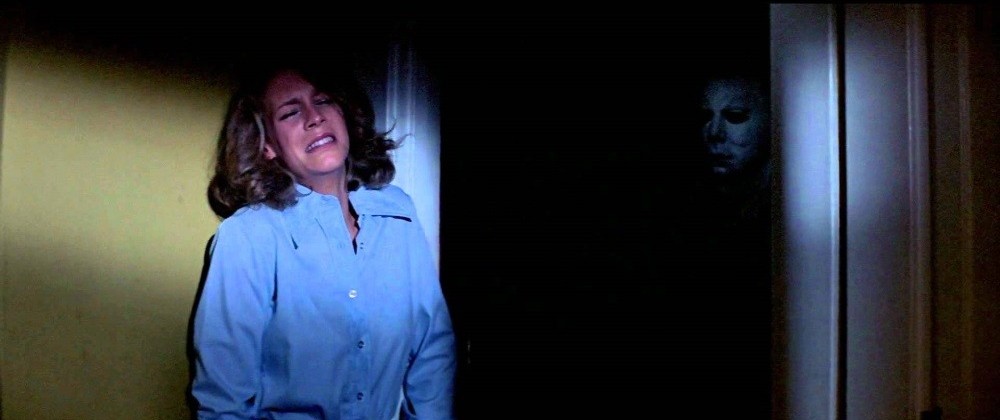

One need look no further than the outcropping of horror remakes in the early to mid-2000s to see proof of this. John Carpenter’s original Halloween, released in 1978, was a carefully crafted orchestration of suspense. There are certainly moments of surprise, jump scares in which Michael Myers suddenly appears to attack the victim. But they are always used as punctuation, a payoff to the suspenseful setup of the prior sequence. Rob Zombie’s remake, on the other hand, released in 2007, is entirely consumed by its desire to surprise. There is no suspense, there’s only shock, which is also why the gore factor is cranked up. The 1978 film left such an impression on audiences that it is coveted to this day. The 2007 remake has already been all but forgotten.

Because suspense lingers. It forces audiences to sit and dwell in the build-up to the payoff and that’s what leaves an impression. It’s the kind of sequence viewers can return to again and again and still feel that same sense of dread as the sequence builds. A film whose horror is rooted in shock will only get worse on repeat viewings because a shock can only be surprising once.

And for a very long time, all audiences got were horror films that cared about surprise. But now, we’re living in the middle of a renaissance of horror films. From It Follows, to The Witch, to Get Out, to Raw, filmmakers have been delivering cinematic horror experiences that can stand proudly alongside the classics of the genre. Instead of turning away from the suspense and framework of horror classics, they’re embracing it and building upon it. In 2018 alone, we’ve had Annihilation, Ghost Stories, and now Hereditary.

These are all films that will be talked about and studied for decades to come. Which makes it even more of a shame that modern audiences have been so inundated with suspense-less horror films that they’re failing to appreciate them. We’re in an era of brilliant filmmakers tackling wonderful material and daring to take viewers to new places, all under the guise of a genre that was all-but-dead ten years ago and Hereditary is just the latest example of why horror fans have so much to rejoice about.