Infamously, in space, no one can hear you scream. But it turns out that on The Great Movie Ride at the then-titled MGM Studios Park at Disney World, somewhere around the year 1998, yes, people can very much hear you scream.

I am three years old, being introduced to the magic of cinema first-hand through my undying love for this Disney theme park. And while several of the attractions interest me, there are none that I am drawn to more than The Great Movie Ride. It’s a spectacle-driven, technicolor whirlwind of an experience, one that feels like lightning in a bottle to my young mind. I am entranced by the Singin’ in the Rain and Mary Poppins-themed sections of the ride, I am thrilled at sheer excitement of The Public Enemy and The Searchers-themed sections, and then I have to quickly shield my eyes and cover my ears. Because ever since being the foundation for one of my very earliest memories, the next section of the ride has utterly terrified me.

Based on Ridley Scott’s Alien, this section of the ride sees you journeying through the labyrinth-esque halls of the Nostromo, coming face-to-face with a full-sized animatronic Xenomorph who descends from the ceiling and lunges at you. And for me as a child, it was simultaneously petrifying and the greatest thing I had ever seen. I couldn’t quantify the feelings or the emotions beyond just ‘scared’ but I knew that I felt this indescribably powerful force drawing me back to this very section of the ride again and again, to experience whatever this feeling was.

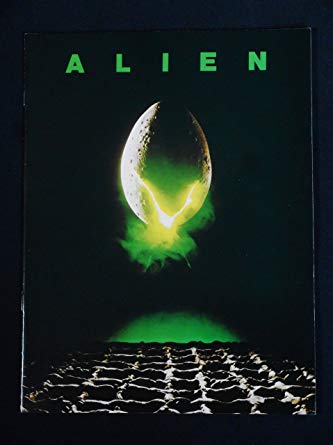

This led to the Alien franchise as a whole taking on an almost mythic importance in my adolescence. The ride section left me wanting more, wanting to see the film itself but at the meager age of three, my parents (rightfully so) felt I wasn’t quite ready for all of that just yet. Funnily enough though, just as in any great Hitchcock film, denying me the immediate gratification only lead to a heightened, nigh unbearable sense of anticipation and suspense. Throughout my childhood, anytime we were in a Hollywood Video (our family’s rental place of choice) I would run to the horror and sci-fi section simply to pick up the case for Alien, to turn it over in my hand and soak in everything about it that I could.

For several years, I would imagine what lay within that case, what tales of terror awaited my young eyes. I asked unrelentingly throughout childhood, every time we were in Hollywood Video, if I could watch it yet. And every time (again, completely reasonably) the answer was no. That is, until a few days after my eleventh birthday, when the answer was finally yes, and I got to witness Alien for the very first time. And then everything changed.

I say all of this in an attempt to say that the Alien films meant monumentally more to me throughout my adolescence than I can really even articulate. (For the sake of clarity, let’s establish up top that we’re only talking Alien and Aliens here. Alien 3 and Resurrection have never really clicked for me. I love Prometheus and Alien: Covenant in their very own wacky and weird ways, but they are distinctly something else. The less said about the two AVP films, the better. Moving on.) Before I had ever seen a single frame of the films, they had been fanning the flames of my imagination for years. And yet they are also films that have very much grown with me, over the course of my life, seemingly morphing before my very eyes as I grew as a consumer of art. In many ways, Alien is kind of the ultimate cinematic Rorschach test for me, in which what the viewer brings to the table is arguably just as important as what the film does. But specifically today, I want to talk about the juxtaposition between Ridley Scott’s Alien and James Cameron’s Aliens, or as I like to call them (respectively), the head and the heart of the Alien franchise.

Let’s talk broad strokes. Released in 1979, Ridley Scott’s Alien was an unexpected sci-fi horror hit that put people like Scott and lead-actress Sigourney Weaver on the map. With its claustrophobic space-set horror, its incredibly effective implementation of Hitchcock-ian suspense tactics, and its gorgeous thematically-charged visuals, the film quickly cemented its legacy as a bona fide modern horror classic.

Considering the amount of profit this made for 20th Century Fox, it’s no real surprise that there was talk of making a sequel for years afterward. But Scott was relatively uninterested in returning, preferring to move onto other projects, leading the idea of a sequel to just kind of meander about on Fox’s drawing board. That is, until this young guy named James Cameron showed up. According to Hollywood legend, Cameron pitched Fox on what his version of an Alien sequel would be with only half of a script actually completed and Fox loved it so much that they were willing to wait for Cameron to finish The Terminator specifically so that he could come back and do Aliens for them. And so he did.

If Alien was an unexpected success, Aliens was a genuine must-see-event blockbuster when released in 1986, capitalizing on the success and the cult of reputation that had built around the first film in the years since its release. It ditched the more somber and meditative tone of Scott’s film in favor of something far more… well, James Cameron-y. Aliens is bombastic, explosive, and viscerally gripping. Gone are the claustrophobic hallways of Alien and in their place are extensive sets and matte paintings, with Cameron literally expanding the horizons of the franchise both in the film’s narrative and in its form. But what makes Aliens work even half as well as it does is the genuine strength and heart of what may be one of the great examples of three-act structure blockbuster screenwriting of the last few decades; Cameron’s script.

As I said, the head and the heart.

Scott’s film is packed to the brim with intellectually-titillating imagery and solemn silence in which the audience is not only left to ,but is encouraged to, contemplate the meaning of the visuals before their eyes. At the time of its release, critics of Alien often belittled it with remarks akin to “it’s just Star Wars meets Jaws” (Honestly, I don’t even see how this is supposed to be an insult? Star Wars and Jaws were two of the best films of that decade? But I digress.) but if there was any film that Scott was really drawing from himself it was Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. From H.R. Giger’s absolutely jaw-dropping design work in the film to the minimalist narrative that spends the runtime whittling itself down to a final showdown between the Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley, a woman who has had to sacrifice everything to come this far, and the invasive, penetrative creature that is after her, the subtext of Alien is frequently heavier than the actual text proper. In a great many ways, it has more in common with arthouse and avant-garde cinema than it does with the subsequent creature/slasher films it helped to inspire.

Conversely, I’m not sure you could convince anyone that Aliens is arthouse cinema. It is Cameron, through-and-through; a nuts-and-bolts piece of blockbuster, spectacle-driven cinema whose primary goal is, to borrow a phrase Cameron would come to use later in his career, make you “shit yourself with your mouth wide open”. And while that is certainly a very different approach than the one Scott took with the prior film, it doesn’t make it a bad one. Because one thing that gets overlooked quite often when people talk about James Cameron’s filmography is a gift he’s had from the very beginning; his ability to create interesting characters and endear them to the audience over the course of the film. This is why characters like Sarah Connor still resonate so strongly and why a film like Terminator: Dark Fate is currently using her return as its biggest marketing hook; Cameron made us all fall head-over-heels in love with that character. Sigourney Weaver’s performance as Ripley in Alien is stunning but it’s not in service of the character, it’s in service of the thematic subtext. We’re not meant to fall in love with Ripley in Scott’s film; that is very much a Spielberg-style technique versus the much more overtly Kubrick-style that Scott is a proprietor of.

But in Aliens, Cameron puts her at the forefront of the film and makes it a film about her coping with the tragedy and loss of the first film through discovering family, owning her motherhood, and sucker-punching her fears in the face from inside a giant mechanical forklift. Gone are the solemn silences of Alien in which Scott wants the audience to be an active participant in the film process because Cameron isn’t about that; it’s about this character and her getting her own hero’s journey… and Cameron getting to make you “shit yourself with your mouth open”.

I am eleven and I am watching the opening frames of Ridley Scott’s Alien, a moment I have dreamt of for years prior to this moment. I finish the film and the feeling I am left with is not what I am accustomed to feeling at the end of a film. I do not feel victorious, I do not feel satisfied. I feel uncomfortable, I feel strangely violated. More than anything, I feel unsure of what I feel.

A few days later, I have convinced my ever-loving father to take me back to Hollywood Video to exchange Alien for Aliens. Conversely, Aliens feels like something more familiar. The broader action beats and the sheer power of Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley as the beating heart at its core are effortlessly endearing, and the incredibly well-crafted narrative feels wholly innovative to my little storytelling-obsessed brain. It immediately becomes one of my favorite films.

In the years since then, I have watched both Alien and Aliens dozens of times apiece. They are both easily within my top twenty favorite films of all time. But whereas my feelings on Aliens have largely remained unchanged (I did get the chance to see it theatrically last year and my sweet Lord, does it belong up there on the big screen), my feelings on Alien have evolved considerably. Because it opened an entirely new avenue of film-watching for me. It taught me that as wonderful as fulfilling, crowd-pleasing films like Aliens are, that perhaps my favorite films are the ones that don’t reach easy conclusions. The ones that do intentionally push you, the viewer, out of your comfort zone and force you to become an active part of the film you are watching.

And I get it, I hold no grudges against my younger self; that’s a lot for an eleven-year-old to process. But I think more so than any other set of films, Alien and Aliens demonstrated the head and the heart of my own filmmaking tastes and experiences to me. The intellectual, the emotional, and how they can both be so different and so powerful in their own ways.