Adaptation is a tricky business.

Taking any beloved property from one medium and attempting to translate it into another is inherently rife with trouble. But perhaps more specifically, turning a beloved novel into an equally beloved film is just short of impossible.

This comes down to the core difference between the two mediums; a novel is comprised entirely of words, they are all that the book has. Conversely, film is an entirely visual medium. The earliest films featured absolutely no words, simply action. Even today, the mantra persists that film is a medium of showing, not telling. Thus, taking a piece of work that is built solely off of telling and turning it into something that is built solely off of showing can be a bit of a jarring transition.

Though there have been hundreds upon hundreds of film adaptations of books over the course of history, perhaps no series is a better-suited lens through which to view the trials and tribulations of adaptation than that of the Harry Potter franchise. Over the course of now-ten movies, J. K. Rowling’s beloved and multi-award winning book series about The Boy Who Lived was adapted and expanded by a total of three different screenwriters and four different directors. Yet with each respective film, the creative team involved took distinctly different approaches in how they translated the source material for the film medium.

The first two films, The Sorcerer’s Stone and Chamber of Secrets, were each written by Steve Kloves and directed by Christopher Columbus. Adapting Rowling’s wizarding world to the screen for the very first time present innumerable challenges that the entire team behind these films do not get anywhere near enough credit. In taking Rowling’s words and putting them on the screen, Columbus and co. were forced to actively shrink the possibilities of the world. Suddenly, Hogwarts wasn’t a place that could look like anything in the mind of each individual reader, it was a set-in-stone location in a blockbuster film.

With the difficulty of these visual choices, the team had more than enough on their plate and ultimately decided to pretty much have Kloves just reformat Rowling’s first two novels from books into screenplays. They crammed essentially everything from the books into the films and while this more-or-less worked for the first film, it proved to be an unsustainable method, both logistically and creatively. On the logistical side, the relatively modest 250-page book for Chamber of Secrets made for a nearly three-hour-long film and the books only got longer from here on in, meaning that the films had to make a change in their adaptational style.

As for the creative side, well, did I mention that Chamber of Secrets is three-hours long? There is a great film inside of Chamber of Secrets but it too often gets lost inside of its own unruly runtime and superfluous scenes such as the entire Forbidden Forest sequence. It’s a film bogged down by its own adherence to the book and demonstrated that perhaps simply filming the book isn’t the best strategy for an adaptation after all.

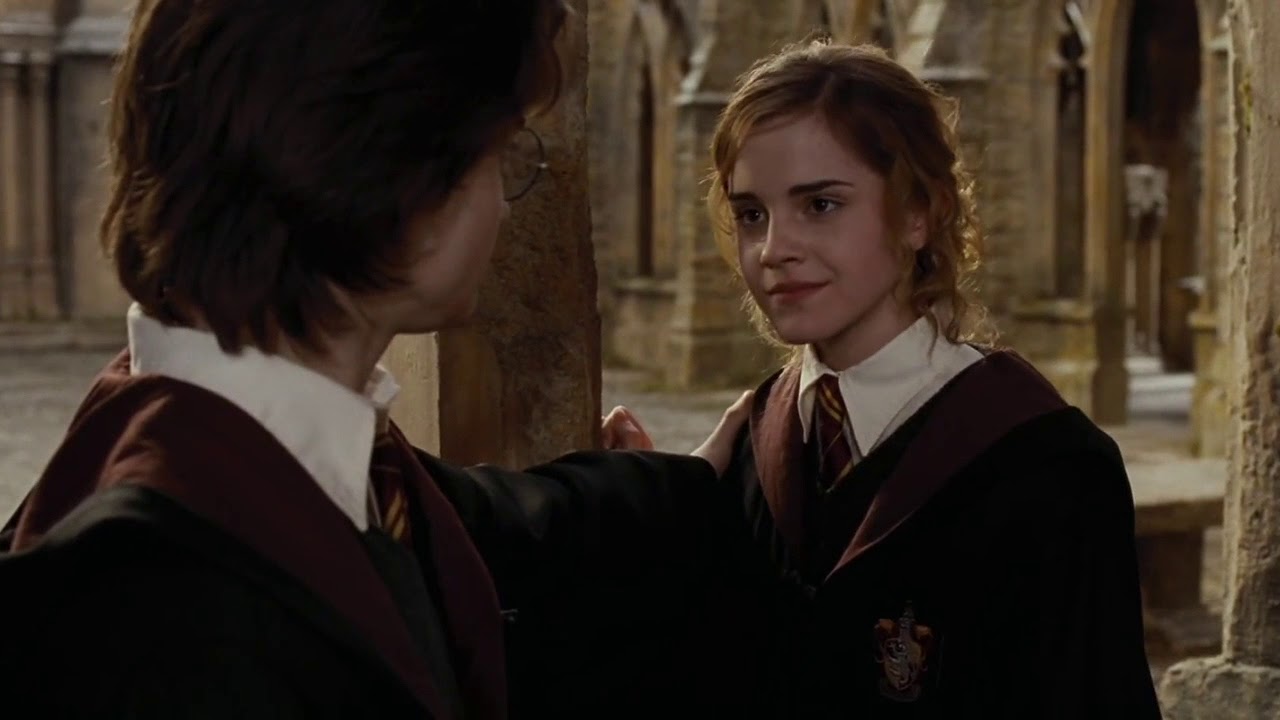

Enter the game-changer that is Alfonso Cuarón’s Prisoner of Azkaban. Continuing to work with screenwriter Steve Kloves, Cuarón set the revolutionary ground-rule that everything in the film should be told from Harry’s perspective. In Cuarón’s mind, this would both anchor the film in Harry’s emotions and serve as an easy ruler with which to decide if a scene from the book makes it into the film. In reality, the film they crafted took even more liberties than that, ultimately shaving all of the fat off of the narrative from Rowling’s book and making the leanest, meanest, and shortest film in the series, so far, in the process.

It’s no coincidence that Prisoner of Azkaban is also, for this writer’s money, the best Harry Potter film by a pretty solid margin. Cuarón more directly rooted not only his visuals but the story-at-large in the themes of Rowling’s book and as a result, the film gets more to the heart of Rowling’s work than her actual work itself. In other words, he made an adaptation that managed to be truer to the source material’s intentions than the source material itself was, something even Rowling herself has essentially said. Cuarón’s film set a brave new precedent for the franchise moving forward, both in terms of quality and in the boldness with which the films could adapt the stories of the books. In not simply making the book into a movie, Azkaban had become the most highly-acclaimed film in the series. Meaning that the next installments would have a new degree of creative freedom and a new high-water-mark to live up to.

Moving forward, as the books got longer and the task of adaptation grew inherently more difficult, Cuarón’s simple ground rule became something of a mantra for the creative teams behind the films: if it isn’t from Harry’s perspective, it isn’t in the film. This became an especially valuable tool for new director Mike Newell and Steve Kloves as they worked on the fourth installment, Goblet of Fire.

Miraculously, Newell took all of the right lessons from his predecessor Cuarón, picking up the baton and running for it. Newell develops and further explores not only the limits of how much he can cut out of the novel and still maintain the core narrative but also how much he can foreground the thematic material of the book in the visuals of the film. In re-utilizing some of Cuarón’s own visual motifs such as physical representations of death or quite literally isolating Harry in the frame, Newell crafts a thrilling chapter that builds on Azkaban’s narrative and formalities in thrilling ways.

Newell has reiterated time-and-time-again that he saw Goblet of Fire as the “ultimate Hitchcock thriller”, equating Harry’s role to that of Cary Grant’s in North by Northwest. In getting to the core structure of the novel’s narrative, Newell was able to drop several of the more frivolous moments from the book and heighten the impact of the narrative. The penultimate example of this is the climactic fury with which the film sticks the landing of Cedric Diggory’s death and Voldemort’s subsequent rebirth. It feels positively gargantuan specifically because Newell and Kloves have reverse-engineered the entire film to build to this moment of payoff, where Harry is thrust violently into adulthood.

Goblet of Fire ends with Hermione asking Harry, “Everything is going to change now, isn’t it?”. She isn’t wrong. With Voldemort back, the entire stakes and structure of Rowling’s novels were changed substantially. Credit where credit is due, the film franchise attempted to do the same.

It just tripped over its own feet in the process.

The fifth film, Order of the Phoenix saw director David Yates coming onboard the franchise and also saw the first-ever absence of Steve Kloves. While the first four films saw Kloves growing increasingly adept at working with various directors to heighten Rowling’s source material, the fifth film decided to change things up and hire a new writer in the form of Michael Goldenberg. In theory, a new director and writer providing a fresh set of eyes and ears to the franchise for this crucial chapter of change seems fitting. In execution, it results in one of the weakest films of the entire franchise.

Rowling’s Order of the Phoenix remains, to this day, the longest novel in the entire Harry Potter franchise coming in at a whopping 766 pages. It is an enormous literary epic that chronicles Harry’s struggles in this post-Goblet world in simultaneously exquisite and excruciating detail. Which means that Yates and Goldenberg, two freshmen to the Harry Potter franchise, were coming in and immediately being given the largest workload possible. I do not envy them.

The resulting film quite literally attempts to rush through as much of the plot of the book as humanly possible. Gone is the artful way in which Cuarón and Newell were able to work with Kloves to edit and elevate the material and in its place is this mad-dash attempt that simply doesn’t work. Key moments for the entire franchise, such as Dolores Umbridge’s ascension to power or even Sirius Black’s death, are literally fast-forwarded through to make room for more plot. It’s only a hair removed from the just-film-the-book strategy the first two films employed and feels distinctly like a step backward in practically every way.

Which is assumedly why the next installment, Half-Blood Prince, immediately set about righting some of the film’s flaws. Kloves was brought back onboard straight-away to work alongside the returning David Yates. But even Yates took great strides to change things up, recruiting highly-acclaimed cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel to work with him on the film and give it a distinctly different look, more inspired by German Expressionism than by any other modern blockbuster.

Yet, the film was presented with a strange challenge. So much of the Half-Blood Prince novel was comprised of Harry simply reading the writing of Half-Blood Prince without knowing who it was that it presented a dilemma; how could the film preserve the novel’s structure without giving away Snape’s identity too early in the film? The answer was, they couldn’t. Thus, Kloves and Yates took the opportunity to remove Rowling’s central framing device from the book, essentially leaning on Dumbledore’s time spent revisiting young Voldemort flashbacks to fill this void instead. The resulting film is surprisingly strong, relying more heavily on mood and atmosphere than the typical Harry Potter film. In adapting Half-Blood Prince, Kloves and Yates had to perform the most complex open-heart transplant of the entire series, essentially switching out the entire narrative for which the book is named, and in focusing on their characters and ever-growing finale on the horizon to provide them a fittingly bleak backdrop, they pulled it off pretty miraculously.

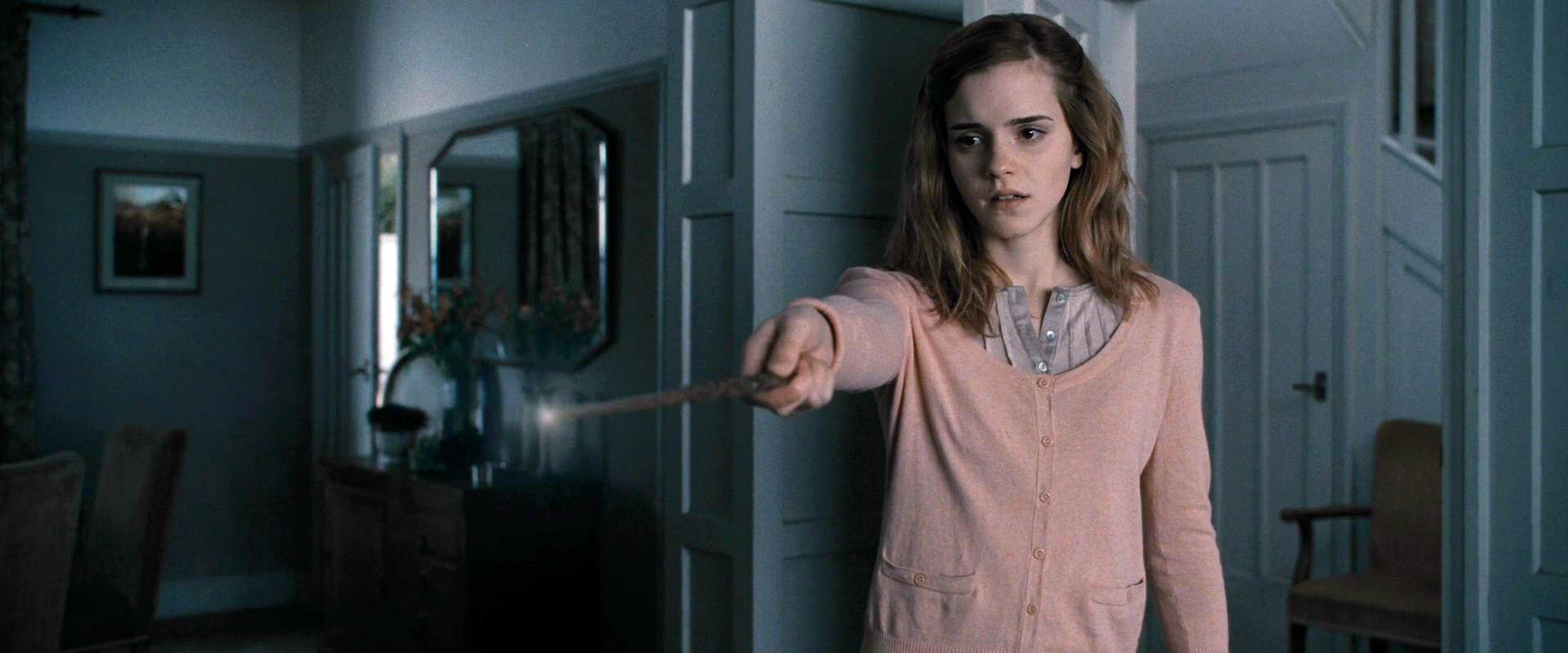

After Yates properly found his footing in working with Kloves on Half-Blood Prince, they moved on to tackle the final book together. Early on, the producers of the franchise realized that they were going to have to tackle this adaptation a bit differently. No matter how much they tried to condense the plethora of narrative in Deathly Hallows, it was going to be nigh impossible to do it all justice in one film. Thus, for both these creative and the undeniably lucrative financial reasons, Deathly Hallows was split into two films. But what could have all-too-easily come off as little more than an excuse to make twice as much money wound up becoming the story’s greatest strength. With the benefit of excess time, Yates and Kloves are able to really marinate in the narrative and the characters, taking Rowling’s novel and fleshing it out in thoroughly compelling fashion.

In the novel, the story begins with Hermione having already Obliviated her parents. In the film, this is the scene that we open on. It’s heartbreaking and sets the precedent for these final two films. Whereas Rowling conveyed the character’s maturity in Deathly Hallows through elements like Ron’s cursing, the film re-translates this for the visual medium. The film itself is more mature in its craft and features the best performances from any of the three lead actors, allowing them the time and space to really dig into their characters and deliver nuanced and powerful performances.

But what happens when a multi-billion dollar adaptational franchise runs out of source material to adapt? Well, they just make up some more of it.

Just a few years after the conclusion of the Harry Potter series proper, Warner Bros. and Rowling decided to tackle a prequel series of films, written by Rowling herself. These Fantastic Beasts films presented an interesting opportunity, in that they were essentially removing the middle-man. Suddenly, Rowling’s words were quite literally going straight to the screen, with director David Yates working off of her scripts this time around rather than Kloves’ adaptations of her work.

Turns out, maybe the middle-man was kind of a necessity. While the first film was a solid-if-flawed film that saw Rowling joyously returning to her talents as a world-building in examining the Wizarding World in America, the second film, The Crimes of Grindelwald, is pretty easily the weakest film in this entire franchise. A large part of this is due to Rowling’s script, which fails to ever feel like anything more than a manuscript for a novel which was accidentally turned into a motion picture. Gone is the carefully calculated precision with which Kloves and directors like Cuarón, Newell, and even later-day Potter Yates converted Rowling’s writings to film, and in its place is a slap-dash story that sees Rowling doubling down on some of her worst tendencies.

Adaptation, in any form, is a tricky business. And there is perhaps no better way to examine the art of adaptation than to look at the Harry Potter franchise in its entirety, warts-and-all. Over the course of four directors, three writers, and several decades this franchise has gone from adapting beloved novels to creating entirely new stories expressly for the film franchise itself. The franchise has seen great adaptations that improve upon the source material, bad adaptations that lose what made the source so special in the first place, and everything in between.

One thing is for certain; as the franchise continues running into its third decade, it will remain forever-intriguing to see how the creative teams behind the films continue to adapt and create this Wizarding World.