Directed by Carl Schultz; Written by Matthew Jacobs; Starring Corey Carrier, Lloyd Owen, Ruth de Sosa; Margaret Tyzack, Paul Freeman

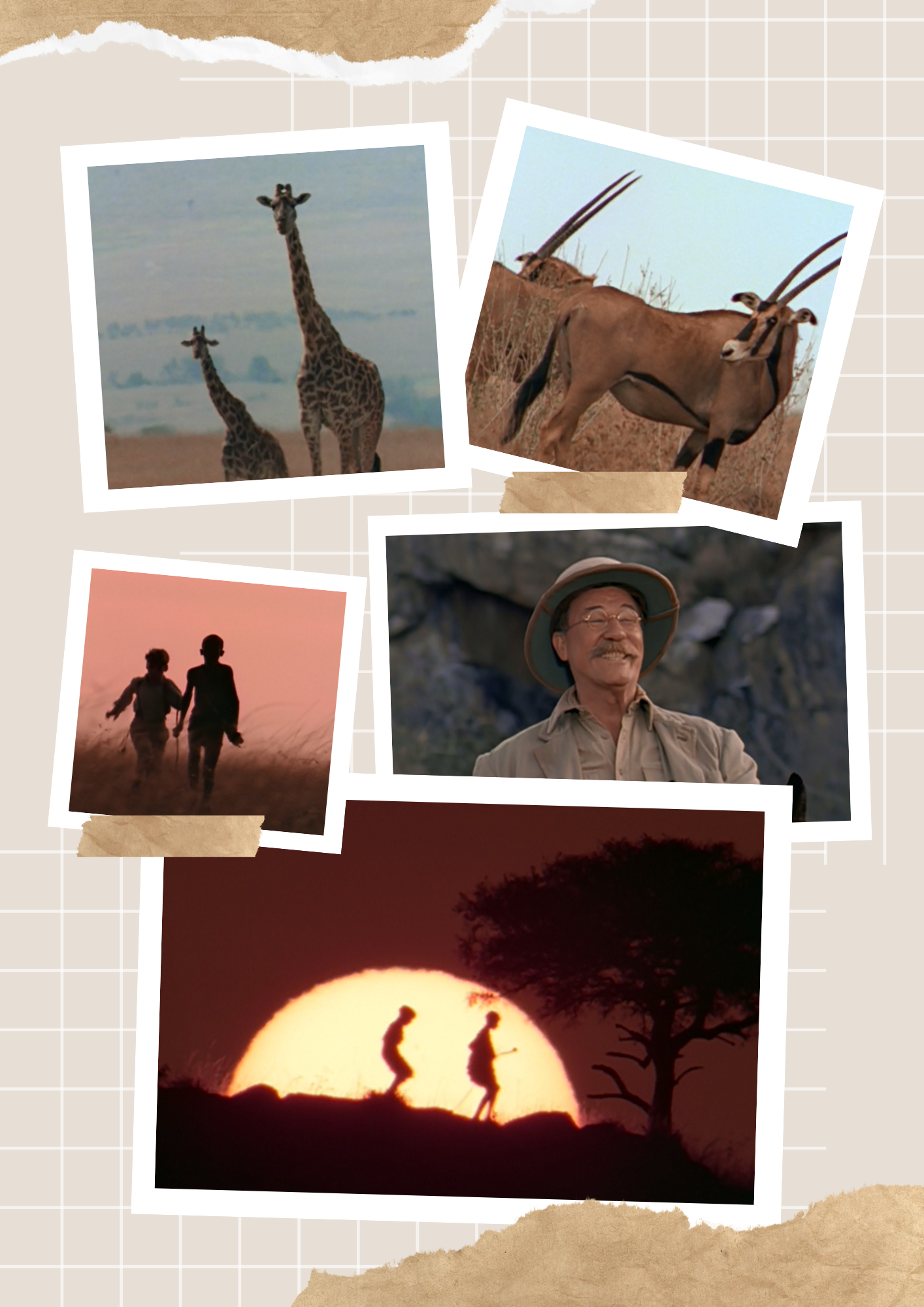

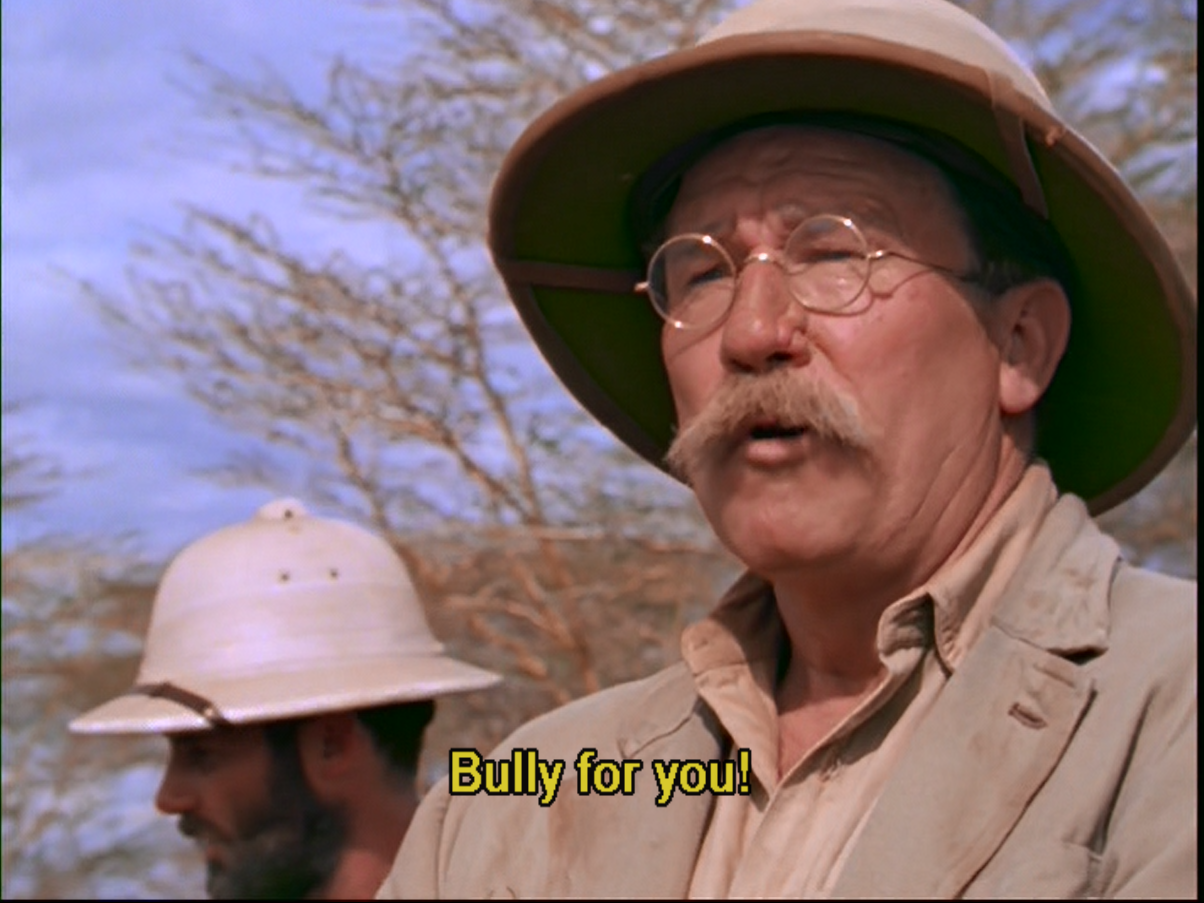

The year is now 1909, and young Indy is 10 years old. He is joined by his parents and tutor, Miss Seymour, on safari in British East Africa, hosted by Henry Sr.’s friend Richard Medlicot on his coffee plantation. Here they meet former president Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt and his son Kermit, as well as taxidermist Edmund Heller and hunter Frederick Selous (Paul Freeman). Selous reminds me a great deal of Jurassic Park’s Robert Muldoon, from the hat, to being a hunter, and currently residing in Kenya.

To give historical context, Roosevelt’s second term concluded in March of that same year, and he is on an expedition funded by Andrew Carnegie to collect animal specimens for the Smithsonian’s natural history museum.

In the area now known as Kenya, British East Africa was the result of British commercial interests (and colonialism). It remained in control of Britain from the late 1800s until 1920.

While Indy is fascinated by the wildlife, Henry Sr. shows a fun, playful side, sneaking up on his wife in the shower with a bucket of water, only to realize she had already left and it’s now occupied by Miss Seymour. Oops! Miss Seymour glares sternly at Sr., who appears appropriately chastised. But this trip seems good for the usually dour father and lecturer, for we see him flirt with Anna, and they make lion noises as they lie next to each other in the tent. It’s a rare glimpse into a different aspect of their relationship, since we primarily see them consoling each other over Indy’s escapades.

Roosevelt teaches Indy how to shoot and gifts him a pair of binoculars, and Indy asks why they must kill the animals, and Roosevelt answers, “Beasts such as these belong in a museum for everyone to share.” (Emphasis on “belong in a museum” is mine.) Indy also learns about the elusive fringe-eared oryx, and he studies the animal and draws it in his diary so that he’ll recognize it if he finds it.

He befriends a local Maasai boy named Meto and enlists his help to find the oryx. They wander all over, evading a lion, speaking to a village elder, and encountering (ugh!) snakes as they examine rock paintings of the oryx. The camp is in an uproar when Indy hasn’t returned by dark.

So when Indy is found and returned to camp, not only does his father order him to bed without supper, but Roosevelt severely scolds him. Indy apologizes, but when Meto comes to his tent the next day, he joins his friend, placing his pith helmet on the covers so it appears he is still sleeping.

Meto shows Indy a group of the oryxes, and they stare in wonderment at the animals. Indy returns to camp to share his findings, explaining why he had gone missing the previous day. He further explains that the oryxes migrated to where they could find root melon. Fire had destroyed the snakes that kept the mole rat population under control, so the mole rats ate the root melon, leaving none for the oryx. Indy explains it’s all connected. One variance can disrupt the delicate balance of nature. (I’ll note that the Wikipedia entry says their diet is over 80% grass, but the broader oryx entry does mention melons as part of the African oryx diet.)

Roosevelt praises Indy for discovering the oryx’s foraging grounds, and the group sets out to collect specimens. But Indy starts to reconsider sharing his discovery when a barrage of gunfire erupts, and he screams for them to stop shooting, that they have killed enough. Roosevelt agrees, and he praises Indy again for his insight.

Their hunting and collecting complete, the group sets off for their next destination. Meto, alone on a ledge, looks out at Indy through the binoculars Indy gave him. The boys wave farewell to each other.

Thoughts

This episode focuses primarily on the delicate ecological balance of the oryxes, but it can be used to illustrate the circle of life in any ecosystem. And the issue of why and how many animals to kill is raised. Particularly in the age before the internet, there was some merit in displaying the wide variety of animals found across the world, so that people could appreciate them and learn about them. But then, that’s why we have zoos. Was it necessary to kill them? Particularly rare species? And what if a population of one species gets out of control and disrupts the delicate balance? Is some “thinning the herd” necessary?

At least during this safari, the focus seems to be on education and sharing rather than merely collecting trophies. However, it doesn’t diminish the obvious colonialism, with the group setting up camp and killing the local wildlife, and then packing up to do it somewhere else just because they can.

On a more positive note, the visuals for this episode are incredible, particularly of the animals. I had to look up the cinematographer(s), and they are Hugh Miles, who also worked on National Geographic Explorer, and Miguel Icaza.

Related DVD Documentaries

- Theodore Roosevelt and The American Century

- Ecology-Pulse of the Planet

History

Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) 26th president of the United States from 1901–1909. Previously served as Vice President until President William McKinley was assassinated. Established national parks and was a distant cousin of later President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Edmund Heller (1875–1939) Stanford University taxidermist. Co-authored Life Histories of African Game Animals with Roosevelt.

Fun Facts

The hunter Frederick Selous is portrayed by Paul Freeman, better known as Rene Belloq, Indy’s French archnemesis in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Freeman also appears as Selous in the episode Phantom Train of Doom.

According to the Indiana Jones wiki, Medlicot and Henry Sr. greeted each other with the college greeting exchanged by Marcus Brody and Sr. in the tank in Last Crusade, but the scene was cut when the episode was re-edited into Passion for Life.

Indy sees snakes and screams that he hates snakes, but at the beginning of Last Crusade, he doesn’t appear to have a problem with them. Not until the train chase do we see this become an issue.

When the downed lion is brought to camp, I think I hear the villagers say “simba,” which translates to lion and is, of course, why Simba is named such in The Lion King.