Jordan Peele is a great many things. An actor. A writer. A director. A producer. A comedian. A regular scene-stealer on MadTV. One half of the modern comedic genius that is Key & Peele. The Academy Award-winning filmmaker behind 2017’s breakthrough success, Get Out. A husband. A father. An all-around exceedingly talented person.

But perhaps above all else, Jordan Peele is a consumer.

This has been evident from his earliest days in the spotlight on both MadTV and Key & Peele, which he consistently used as platforms to skewer or parody various films, television programs, and real-life events. You don’t get sketches like Key & Peele’s The Wire parody without them being massive and well-versed fans of said property. But Peele’s role as a consumer, first and foremost, has become increasingly relevant in the more recent stage of his career. No longer is he merely a member of the audience, he has become a storyteller in his own right.

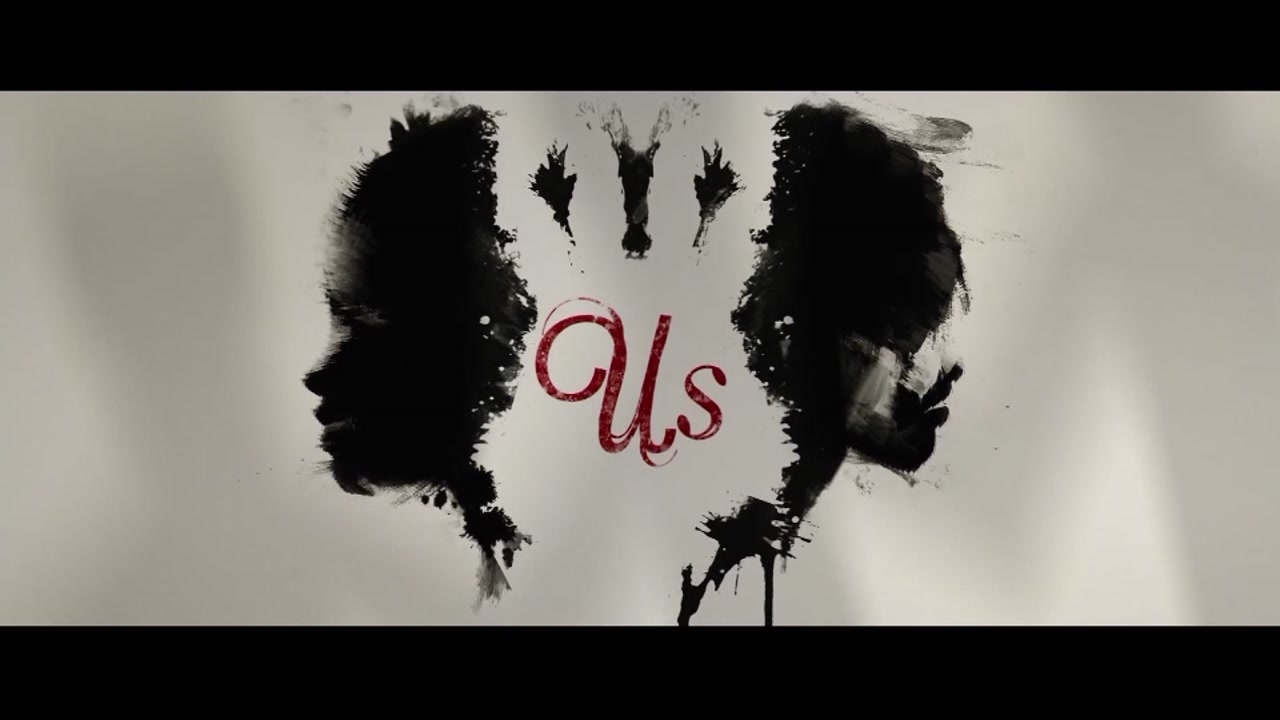

Which is why the internet has been positively littered with articles and interviews detailing Peele’s meticulous film-consumption process for himself, his cast, and his crew in the lead-up to his new film, Us. In an Entertainment Weekly article a few months back, Lupita Nyong’o shared that Peele gave her a list of ten horror films to watch before filming began to establish a “shared language” between the two of them; The Shining, The Babadook, It Follows, Dead Again, A Tale of Two Sisters, Funny Games, The Birds, Martyrs, The Sixth Sense, and Let the Right One In. Similarly, Peele himself has been one of the primary assets for Universal’s marketing team, making the rounds on both television and web-based programming, proving his horror fan credentials time-and-time-again by listing off references and trivia like a true aficionado. In one of the best interviews Peele has given on said circuit, he discussed the role and impact of horror films in his life, his complex relationship with them, and how George A. Romero’s seminal classic Night of the Living Dead felt so revolutionary, saying;

“The films never really served our identity. People with black skin didn’t fare very well. It’s kind of a confusing and unfortunate thing for me growing up, sort of being in love with horror movies but also not feeling very well represented.”

In a later interview, he went on to elaborate that having Us center around a “nuclear” African American family was his way of putting out into the world what he “wished he had had” as a child.

All of this to say, Peele has been very open about just what deep and lasting impacts art has made on him throughout his life. So when Us opens on a shot of a young African American child in 1986 consuming various television ads and programs, it’s something to take notice of. Perhaps even more crucial is the fact that the screen is framed in such a deliberate fashion that we constantly see the reflection of young Adelaide in the screen itself, especially as she flips between channels and sees her own reflection amidst the darkness.

Because one of the most interesting layers of Us’ subtext is how art influences its audience.

The big twist at the end of the film is that the young Adelaide we see during the film’s opening is actually not the adult Adelaide we spend the film with. Rather, her ‘Tethered’ doppelgänger Red attacked her and switched places with her back in 1986 in the Hall of Mirrors. This does what all great twists should do; it drastically and violently recontextualizes the entire film that has come before it. It was the young Adelaide who spent her childhood watching Hands Across America ads and being utterly satiated with the red-blooded patriotism of Ronald Regan’s America of the 1980s, who actually liberated all of the Tethered and planned this entire attack on the surface world. In dressing the entire culture of the Tethered up in red jumpsuits and planning for them to recreate the pose of Hands Across America, the art by which she was molded directly shapes the course of her life.

Similarly, the Wilson family’s interactions are constantly framed by pop cultural references. In perhaps the film’s funniest instance of this, Gabe suggests that in order to remain safe they should hunker down in the house and “Home Alone” the Tethered. To which both of his children, Zora and Jason, respond by asking what Home Alone is. It’s a good gag but it also effectively foregrounds this central idea of the film: Gabe thinks and acts fundamentally different from his children because they have been impacted by completely different generations of art.

While the film has a great many references to film, television, and music, the most prominent of them all is the use of Luniz’s song, I Got 5 on It. This song makes its first appearance as the Wilsons are driving to Santa Cruz beach. Here, again, the film showcases the distance between the art that influenced the children and their parents, as Jason has no idea what the song is and Zora and Gabe disagree about the song’s true meaning.

The song makes its second appearance playing in the background over the Ophelia speaker system in the Tylers’ home as the Wilsons attempt to formulate a plan of action. But by far its most interesting use is in the climactic third act battle between Adelaide and her Tethered counterpart, Red. Here, shots of the two fighting are interspersed with shots of their respective teenage selves performing ballet dances as the score turns into a gradually crescendoing orchestral rendition of I Got 5 on It.

During an earlier flashback to young Adelaide’s parents taking her to a psychiatrist, this theme of art playing a crucial role in one’s development is pretty much outright stated, as she suggests that Adelaide’s parents encourage Adelaide to draw, sing, or dance so that she can “tell us her story”. It isn’t until later that the young Adelaide in this sequence is, in fact, a young Red who does not yet know how to speak. This early scene is made all the more interesting in hindsight when considering the weight and ramifications of the climactic dance sequence.

I Got 5 on It wasn’t released until 1995, just shy of a full decade after Red had switched places with Adelaide. Meaning Red grew up with the song in her teenage years, just as other people of her generation such as Gabe would have. It is a common influence among them, a shared impression, a piece of art that has meaning for her as it does for him. So having this orchestral score of I Got 5 on It swell as Red and Adelaide are literally joined together in the same frame for the first time in the entire film is a brilliant artistic stroke on Peele’s part. One that not only excellently foreshadows the twist that is to come but also subconsciously roots the audience even further in Red’s perspective without us even realizing it yet. Through her dance, through her own interpretation of the art, she is quite literally showing (rather than telling) us her story.

Which brings us to the meta-layer of this theme: the fact that this film is a reflection of the art that has shaped Jordan Peele. It’s there in the formal references to literally dozens of horror classics(The Shining and Halloween, just to name a few), it’s there in the way he lovingly places wardrobe choices (Jaws and Thriller T-shirts) and musical cues (The Beach Boys’ Good Vibrations), but most pressingly, it’s there in the representation of America. As Peele told Vanity Fair at the SXSW premiere of Us;

“Hands Across America was this idea of American optimism and hope and Ronald Regan-style ‘we-can-get-things-done-if-we-just-hold-hands’. It’s a great gesture but you can’t actually cure hunger and all that… That was when I was afraid of horror movies. That’s when the Challenger disaster happened. There are several ‘80s images that conjure up a feeling of both bliss and innocence, and also the darkest of the dark.”

And this film sees Peele tackling all of that, head-on. A great many writers have pointed out that the film deals quite a bit with the concept of privilege, what with the disparaging gap of resources that divide the Tethered and surface-dwelling counterparts, and that’s certainly true. But what’s of far more interest to me is the way in which Peele quite literally paints the wreckage and casualties of the ‘80s, whose ghosts still haunt modern-day America, up in literal red.

The Tethered live within forgotten tunnels underneath the country, festering just below the surface, because they were a failed experiment of the ‘80s that were just cast aside and left to rot. Through this narrative, the Tethered become a literal embodiment of the damage done to the country by the very things Peele is discussing; the ignorant and destructive excess of the ‘80s. Or to put in more direct terms, Reaganomics.

And sure the red jumpsuits they’re wearing are for the in-narrative purpose of evoking the Hands Across America symbol, but it’s also hard to ignore just how much that particular shade of red resembles the Make America Great Again hats that have become so ever-present among a certain subset of modern Americans. It’s certainly no coincidence that when the Tethered first invade the Wilsons’ home, their answer to the question of who they are is simply;

“We’re Americans”

The final shots of the film see the camera quite literally sweeping across the fruited plains as the full-bodied version of Le Fleurs, the song reduced to mere muzak in the original Hands Across America ads, blares over the footage. Yet these gorgeous landscape shots of America are divided right down the middle, by a streak of blood red. I’m not sure any horror film of the Trump presidency has sent bona fide shivers up my spine quite the same way this film’s final shot did.

You can feel the warring factions of Peele’s perceived “innocence” and “darkest of the dark” of the ‘80s in the formal elements of the film and its ramifications. On the one hand, there is genuine change happening in cinema, just as it is in America right now. Peele has become one of the most respected auteurs of the horror genre, and in doing so is now creating and inspiring the kind of art and representation he longed for as a child. On the other hand, the film is brutally honest about the state of our nation and the dire, divided times we are living through.

The best horror films have always captured the present-day culture as it is. And that’s why Us is so damn terrifying. In capturing not only the horror of this very moment in America, but also the last thirty years of art, propaganda, and American history, it holds a mirror up to our society and forces the audience to look at what has become of us. Much like the recurring visual motif of Adelaide and/or Red peering into a dark screen and seeing only their own reflection peering back at her, Peele’s film allows us to see the enemy and realize that the enemy is us.