Since the dawn of the genre, every truly great horror film has had one thing in common: they’re relatable. In order for a film to truly get under an audience’s skin, they must be able to relate to it in one way or another. Whether that be through the characters, through the setting, or through the plot, something about the film must feel real to them in order to have any chance of actually scaring them. Audiences weren’t scared of Frankenstein because of the monster, they were scared because of the monster they saw within humanity. Get Out wasn’t scary because of the lobotomizing, it was scary because the world and topics it tackled felt all too familiar. But in the past few decades, studios have found a convenient and far-too-easy way to circumvent this hurdle; they can simply tell the audience the film is real.

‘Based on a true story’.

In and of itself, this statement gives away exactly how accurate the film’s depiction will be. The first word is ‘based’, insinuating that the true story may very well have been the jumping off point but it is not a factually-sound replication. The other tell-tale sign is the use of the phrase ‘true story’. A story is a not an event that has actually occurred in reality, a story is the telling of said event, which leaves room for embellishment, bias, and personal taste. Already, just from the phrase alone, we are at least two steps removed from the actual truth of the matter.

Film itself essentially started as the basic retellings of personal truths. When the Lumière brothers made L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, horrifying audience with the 50-second long short that simply documented a train coming towards the camera’s peripheral, they were simply attempting to share a truth of their lives as a story. As the medium evolved, so too did the complexity of the truths being told. Citizen Kane was inspired by the life of William Randolph Hearst, films like Kubrick’s Spartacus were inspired by historical epics that had been being told as stories for centuries prior.

And yet it was clear that these films were not truth, nor did they ever attempt to pose as such. It wasn’t until horror, the little genre that could, got its hands on the idea that it became a selling point.

The first real step into the world of ‘based on a true story’ was taken by Tobe Hooper in the fall of 1974, with a little film called The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Not only did the film advertise itself as being the retelling of a true event, Hooper shot the film in a style that was deliberately similar to that of documentaries of the time. This aesthetic choice was Hooper’s solution to how to make up for the fact that the film didn’t have the budget to compete with more classically stylized films of the time, but led to some unruly side-effects.

Audiences bought into the idea that this massacre was a reality thanks to the potent combination of the advertising and Hooper’s visuals and the film became widely revered as one of the scariest horror films of all time. But the reality is, Hooper’s film was entirely fiction. The only truth of the entire film is that Leatherface was inspired by Hooper’s fear of Ed Gein, a real-life serial killer who did decorate his home with appliances and accessories made out of the skin of his victims. It didn’t matter that none of the film’s core elements were real, they had convinced audiences that they were and that’s all that mattered.

This film’s success led to several other ‘true story’ horror films like The Amityville Horror or The Entity to claim the moniker as their own and sell the films to audiences as retellings of actualities. Even films that were exceedingly loosely inspired by real-life headlines, such as Child’s Play or A Nightmare on Elm Street, began to use the marketing tactic as a selling point.

Of course, all of these stories were being sold to pre-internet audiences. There was no definitive informative source that viewers could run to and check how much of the story was factually accurate. One would think that the internet boom would put an end to such a trend, but in reality, all it took was one exceedingly clever marketing campaign to use the internet in its own favor instead, and suddenly the solution had been found.

The Blair Witch Project was released in 1999 and became one of the most profitable films of all time (based on initial budget to income ratio), thanks to its revolutionary marketing campaign. The film took Hooper’s original logic from 1974 and pushed it to the next logical step; don’t just make it aesthetically reminiscent of documentaries, make it a documentary. The film looked real and had an online marketing campaign all about how the three teenagers in the film had gone missing looking for the Blair Witch and all that was left of them was these freshly-discovered tapes. If audiences weren’t sold on it by the film itself, the internet campaign served to cement the notion that this was completely real.

In reality, the film was entirely fictional and the teenagers were nothing more than actors and film school students. But their little film changed the entire genre, for better or worse. Found-footage had been introduced as the ultimate form in which to sell audiences on the truth of the horror they were watching. Thus a decade later, multiplexes were overflowing with found-footage films like Paranormal Activity, The Last Exorcism, or Unfriended.

In today’s marketplace, the ‘based on a true story’ tag is in a bit of a strange place. Found-footage has fallen out of vogue and audiences have, inevitably, gotten wise to the strategy. Yet this hasn’t stopped studios from trying to sell films on their correlation to truth. Films like The Conjuring and its sequels have continued to insist they are based on true stories, with varying degrees of success, but continue to make blockbuster amounts of money at the box office. The just-released The Strangers: Prey at Night is a sequel to a hit ‘true story’ film whose only truth was that the writer once got scared by a knock on the door in the middle of the night. Yet somehow, even the sequel is touting the ‘true story’ tag in hopes of recruiting more viewers.

The other big ‘true story’ film that is making a difference in the modern landscape of cinema is the one that may be showing us the next stage of horror marketing.

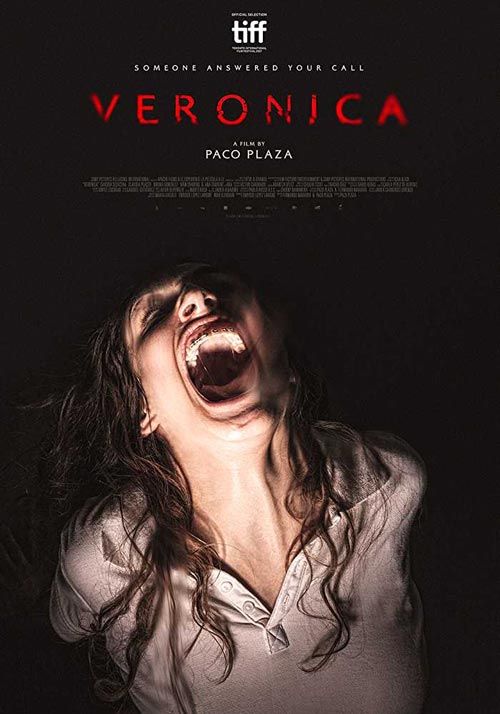

Netflix is selling Veronica as one of the scariest films of all time, so close to reality and so traumatizing a viewing experience that viewers may not be able to handle it. They have done this by playing up social media reactions to the film and re-emphasizing that it is, again, ‘based on a true story.’ In the same way that The Blair Witch Project utilized the internet in its favor, Netflix has been using the instant word-of-mouth capabilities and reactions of social media to build a cult-like buzz around Veronica. Even as audiences check out the film for themselves, thousands upon thousands have felt obligated to share their own take on whether the film lived up the hype, which in turn only generates more buzz for the film.

It is the natural evolution of the kind of marketing studios have been using to sell horror films for years but now with one vital addition. Instead of just trying to convince audiences that the film they’re watching is real so that they will, in turn, be terrified by it, studios are now trying to convince audiences that a film is utterly terrifying before they’ve ever even seen it.