“You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullshit and you know it.”

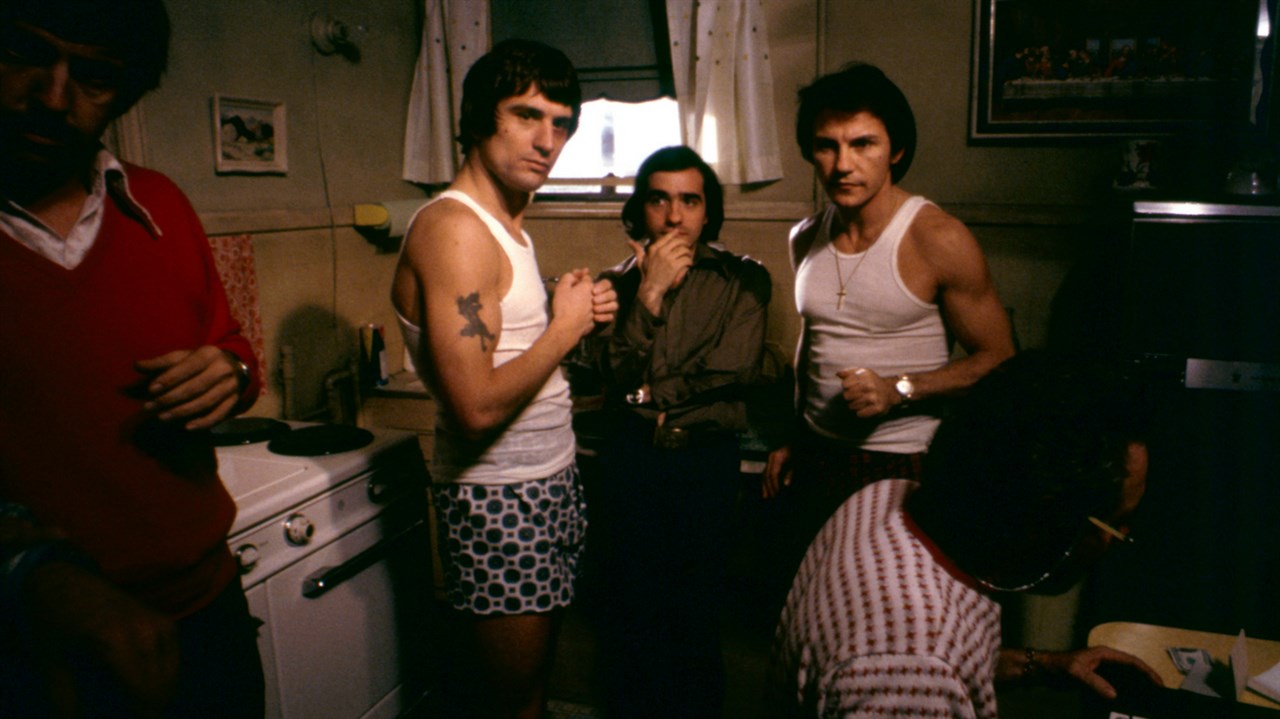

Such are the first words uttered against a canvas of utter darkness in the opening seconds of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets. Fittingly so. For though it was far from being Scorsese’s first film, released in 1973, Mean Streets was an artistic crystallization for the filmmaker. Through the barebones narrative of following the everyday lives of Charlie, Johnny Boy, Tony, and Michael, Scorsese was able to explore so many of the themes and visual motifs that would come to define his entire filmography: religion, guilt, cleansing wrath-like violence, and so many more. But one of the most striking aspects of Mean Streets is a central theme that Scorsese has carried with him for decades now, like a cross; the deconstructive dissection of the very concept of masculinity.

Take Charlie, the central character of Mean Streets as played by Harvey Keitel. He’s a young Italian-American man, struggling to bridge the gap between dutifully following the ideals set by his God-fearing Catholic faith and living up to the idea of what he has been taught a true man should be. The adult males in Charlie’s life who he has had to look up to and learn from have essentially all reinforced standard masculine tropes and left little room to allow for emotional maturity or growth. The closest thing to a father figure in his life is that of his uncle, Giovanni, a ruthless mid-tier gangster.

Throughout the film, we see Charlie and all of his associates (Johnny Boy, Tony, and Michael) desperately clinging to these perceived ideas of masculinity and suffering because of it. Charlie finds himself incapable of giving or receiving any kind of emotional support to his girlfriend, Teresa, so much so that he keeps their relationship a secret because he’s ashamed of her epilepsy. Johnny Boy constantly tries to reenact the kind of lifestyle he’s seen people like Giovanni lead before him, only without the money or power to back it up, which ultimately results in him being shot to death. Tony tries to run his bar as a legitimate establishment front for a seedier underbelly, as he’s grown up witnessing, but is unable to keep his footing and everything subsequently spirals out of control. Michael is a low-tier loan shark who has practically made himself out to be a dime-store version of Giovanni and ultimately feels such a need to prove his bona fides as a man that he kills Johnny Boy, his close friend, over disrespect.

It’s not hard to see Scorsese in Charlie in Mean Streets. In fact, Scorsese actively invites the parallels, using his own voice for Charlie’s internal monologues rather than Keitel’s. It is in this way that Scorsese is able to go beyond simply offering a slice-of-life style film about the streets of New York; he’s instead able to take his own experiences, fears, and desires and grapple with their meaning through cinema, with the damaging expectations and baggage that come from the idea of masculinity lying squarely at the forefront.

This all grows all the more interesting with how Scorsese and cinematographer Kent L. Wakeford not only frame the men themselves but also the world they’re encompassed by. They’ll center the frame on a character, only to move the camera around them. The resulting effect is that of the backdrop, the world that the character is inhabiting, moving around them. Take for instance the initial conversation between Charlie and Michael as they discuss the issue of Johnny Boy’s extensive unpaid debts. It’s shot in a fairly traditional shot-reverse-shot setup, but as the conflict of the conversation grows and evolves, the camera causes the environment to surge in the direction of whoever is in power at that moment. When Charlie tries to bat away the allegations, the world around him moves in his direction. But when Michael grows adamant about there being dire consequences if the debts aren’t paid, the tide turns as the backdrop around them flows like an unstoppable current toward Michael.

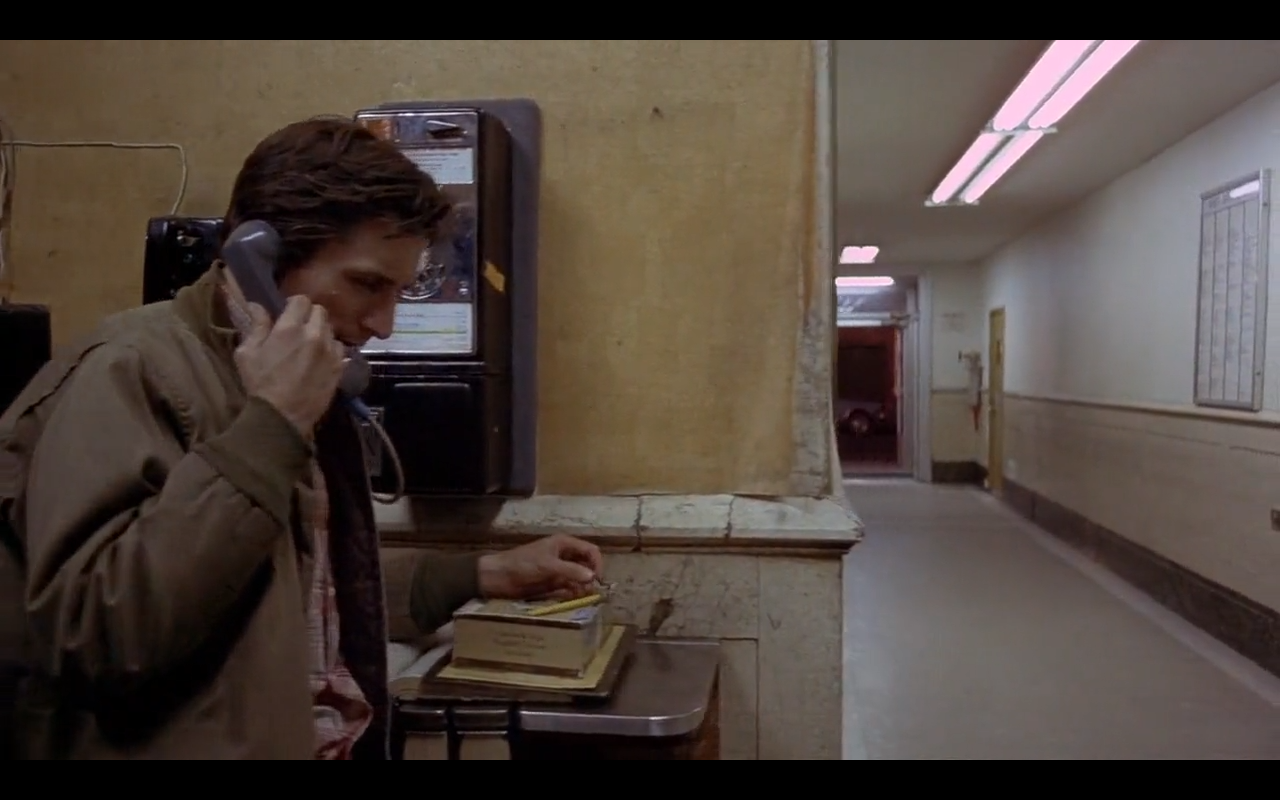

It’s an ingenious technique, one that Scorsese would bring with him to his work on Taxi Driver three years later, in 1976. Whereas Charlie was a social butterfly willing to destroy himself in the name of keeping up appearances, Taxi Driver’s protagonist, De Niro’s Travis Bickle, is a lonely soul from the get-go and Scorsese exploits this to continuously transcendent results. In Bickle’s opening conversation with his boss about wanting to work nights as a driver, the camera causes the environment around Bickle to surge up and down depending on how empowered he is at that given moment. But the most poignant extension of this visual idea comes in the form of Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman’s most brilliant shot in the entire film.

After blowing a date with Betsy, Bickle calls her and pleads with her to give him a second chance. But before he’s even close to done speaking, the camera drifts away from him, his environment moving to the point that he is entirely removed from the frame. Because the conversation is over. Life has passed Bickle by and no matter what he does, he no longer seems to be able to find his place in the world.

Such is the tale of the Paul Schrader-scribed Taxi Driver, an intimate and personal dissection of the dangers of masculinity. It takes the macho tendencies reinforced by such ideals to their logical and violent conclusions. Bickle spends the entire film looking for excuses to commit acts of violence and ultimately finds his greatest yet at the end of the film, in killing Sport and his gang. He’s praised as a hero for it but his intentions were far from noble. He takes Betsy to a porno theater on their second date because he thinks that’s what men are supposed to do, be forward and forthcoming about their sexual desires.

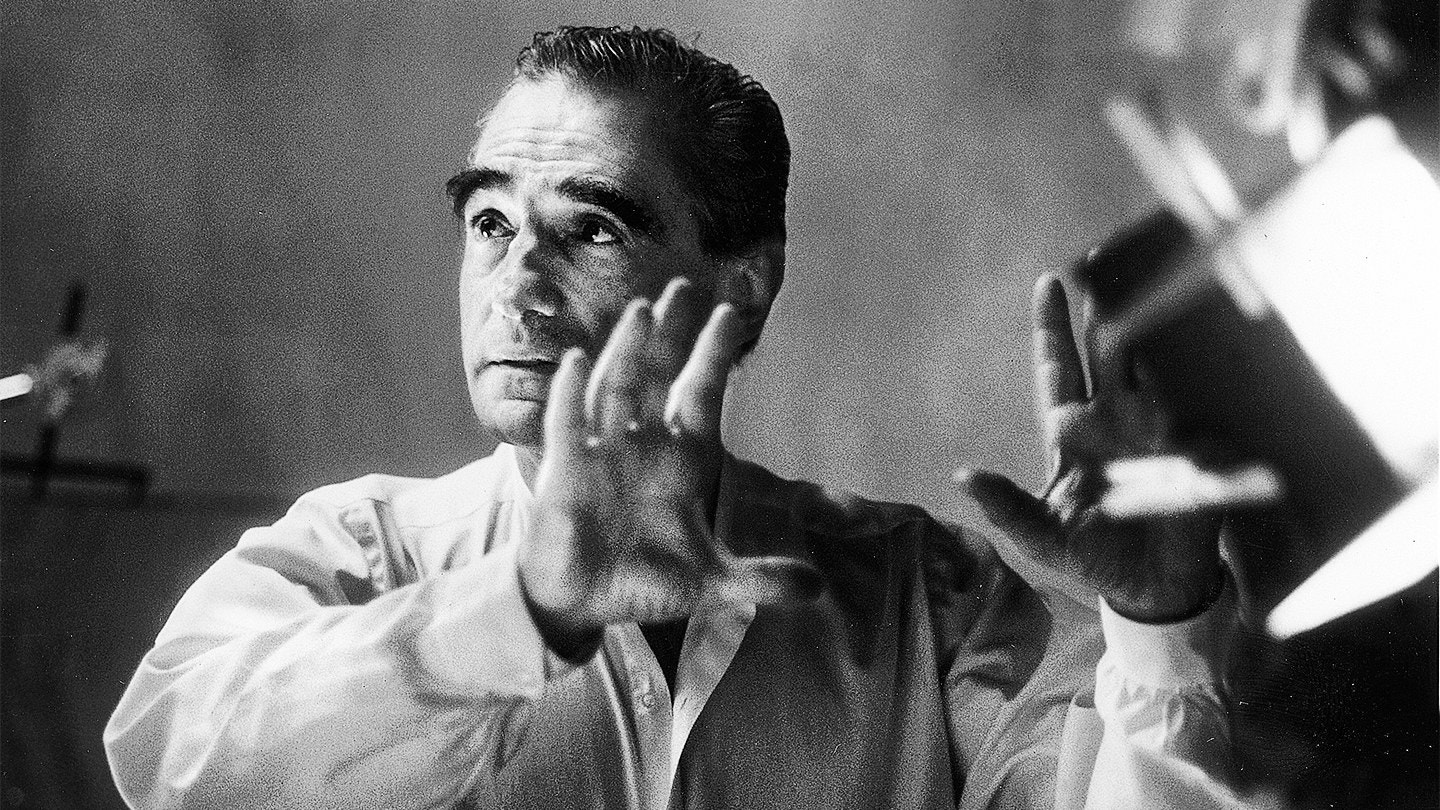

It’s no coincidence that in a 1976 interview with Roger Ebert, Scorsese referred to Taxi Driver as his “feminist film”, saying;

“It takes macho to its logical conclusion. The better man is the man who can kill you. This one shows that kind of thinking, shows the kinds of problems some men have, bouncing back and forth between the goddesses and whores.”

It’s worth noting here that Scorsese plays a role in this film as well, as a literal devil on Travis Bickle’s shoulder. He appears as a passenger in the cab who is so enraged by his wife’s infidelity that he details to Bickle how he’s going to kill her with a .44 magnum pistol, the exact weapon that Bickle subsequently asks for when he goes to buy a gun. Not only does this feed into the larger theme of masculinity essentially being a paltry act that doesn’t really exist beyond false expectations, but it also sees Scorsese once again actively inviting parallels between himself and his characters. This vendetta, this investigation into the fallout of such masculinity is clearly deeply personal to Scorsese.

From here, we arrive at perhaps Scorsese’s most scathing indictment of all, 1980’s Raging Bull. In reteaming with much of his Taxi Driver team, including Schrader, Chapman, and De Niro, Scorsese utilizes the true-life story of Jake LaMotta as a means to completely deconstruct the very idea and resulting toxicity of masculinity.

If the shot of the world literally and figuratively passing Travis Bickle by during the phone call scene was the visual foundation for Taxi Driver’s entire thematic thesis, then the opening shot of Raging Bull serves as its own. The slow-motion shot of LaMotta inside the ring, fighting against no one but himself, framed so that the ringside ropes form a prison from which he cannot escape is the kind of blisteringly brilliant shot filmmakers could spend their whole lives striving for and never achieve. Both in the ring and at home, LaMotta is a slave to his own violent tendencies. He’s unable to separate the two, he merely sees it all as conflict, in which the only winner is the one who can inflict the most pain.

No one plays a more pivotal role in illustrating this point than editor Thelma Schoonmaker, whose bold cuts from domestic arguments to directly inside of an already-in-progress boxing match serve to heighten Scorsese’s entire message. Raging Bull was Scorsese’ first time working with Schoonmaker after having spent years searching for a regular editor (various friends including Brian De Palma helped him compile a final edit of Mean Streets, while Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Taxi Driver, and New York, New York all saw him routinely turning to the incomparable Marcia Lucas to get the pictures across the finish line) and he hasn’t ever worked without her since.

Scorsese and Schoonmaker have continued to explore different facets and corners of this idea over the decades in films such as (but certainly not limited to) The Color of Money, The Last Temptation of Christ, GoodFellas, The Departed, and The Wolf of Wall Street. But what’s grown increasingly interesting to watch is how Scorsese views and tackles this same theme as he grows older. Nowhere is this life-long crusade of dissecting the ramifications of masculinity more fascinating than it is in The Irishman.

Scorsese’s latest film centers on the tale of Frank ‘The Irishman’ Sheeran, played by De Niro. It is a brutally honest and gutturally raw poetic meditation on the consequences of Sheeran’s actions throughout his life. As a soldier, as a hitman, as a politician, and most crucially, as a father.

De Niro plays Sheeran as the epitome of the strong-and-silent type. He becomes such a valuable resource to the Bufalino crime family specifically because he is so predisposed to follow orders without so much as a second guess. As he says early on,

“You followed orders, you did the right thing, you got rewarded”.

It is only at the end of his life, the point from which an elderly and frail Sheeran narrates the film, that the casualties of his actions truly haunt him. Nowhere is this more powerful than in his scenes with his daughter, Peggy Sheeran, played by Lucy Gallina and Anna Paquin, respectively.

Throughout the film, Peggy keeps her distance from her father. As Frank himself states midway through the film, she’s afraid of him. She’s seen who her father is and what he does for a living, and more so than arguably anyone else in their family, she understands the weight of his sins. All of this culminates in their final scene, in which a deathly-ill Frank goes to see Peggy, only for Peggy to outright refuse to even acknowledge him. As Frank’s other daughter, Dolores, later tells him;

“Daddy, you have no idea what it was like for us. I mean, we couldn’t go to you with a problem, because of what you would do. You know, we couldn’t come to you for protection, because of the terrible things that you would do.”

Frank’s adherence to the expectations of masculinity ultimately isolates him from his family, leads him to do terrible things to his closest friends, and leaves him a bitter old man with nothing left at the end of his life but regret and a petrifying fear of finality.

There isn’t a more emotionally devastating hour of film in Scorsese’s entire filmography than the final act of The Irishman, as the full weight of Frank’s own actions comes crashing down upon him and us. At the end, as a scared and uncertain man, he’s forced to question his entire life, his entire line of thinking, his entire belief system, and the entire idea of what being a man truly is. Which is precisely why a line like, “What kind of man makes that call?”, is so utterly heartbreaking.

Martin Scorsese has spent decades wrestling with his demons in his own personal cathedral; the cinema. Yet none of them have been as routinely innovative and daringly bold as his continuing investigation into what it means to be a man. As he’s aged, the films have gotten increasingly introspective. We’ve seen Scorsese himself become a man in the process. The hungry, ambitious kid who funded Mean Streets with his own pocket change is markedly different from the reserved and eloquently poetic man who crafted The Irishman. The end result is only a more comprehensive whole because of it; a thorough and staggering dissection of what it means to be a man across several decades of remarkable cinema.