The year is 1931. It is February 14, Valentine’s Day. Universal’s production of Tod Browning’s Dracula has just been unleashed on an unsuspecting public and the world will never be the same.

Audience members are so thoroughly disturbed by what they’re witnessing on-screen that there are widespread reports of people fainting or collapsing in the theater, mid-screening. The Roxy Theatre in New York City is selling tickets to the film faster than they can print them, with a total of 50,000 tickets being sold within the first forty-eight hours of release, an unprecedented accomplishment. Executives at Universal Studios who were wary of the young Carl Laemmle Jr.’s faith in such a film, who feared that audiences wouldn’t respond, breathe a collective sigh of relief. Dracula goes on to become one of the highest grossing films of the year and single-handedly pulls Universal out of debt. It becomes the kind of event-film, word-of-mouth sensation that continues to sell out screenings for weeks-on-end.

The message is loud and clear; horror has hit the big time.

The ramifications of Dracula’s success are nigh impossible to measure. The film itself and the fortification of the horror genre as a viable artistic and commercial endeavor for major studios changes everything in Hollywood. Suddenly, it was an arms race to see who can capitalize on this barn-storming success. But of course, Laemmle Jr. and Universal Studios were leading the pack with the second in our make-shift trilogy of seminal horror classics from 1931: James Whale’s Frankenstein.

It may not immediately seem like an obvious choice to jump from Dracula to Frankenstein, but it doesn’t take much digging to see exactly where Laemmle Jr. might have gotten the idea from. Hamilton Deane, the same actor/writer/producer who had spear-headed the initial Dracula stage-play which Universal’s film looked to for inspiration, had commissioned playwright Peggy Webling to pen a stage-play version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein for him in 1927, which then toured in unison with the production of Dracula. Following this, John L. Balderston, the same playwright who had adapted Deane’s original Dracula for the Broadway revision which Lugosi starred in, penned a revised version of Webling’s script for a planned Broadway iteration of the play. Despite this, the revised script was never used as the plans for the production fell through. But it meant that Balderston had a fresh script eagerly awaiting Universal when they came looking for another horror film.

And pretty obviously, that was the initial mission statement for Frankenstein; just do Dracula again. Take a recognizable intellectual property (i.e. a classic piece of literature) that centers on the gothic or macabre, purchase the rights to a stage-play that has already done the heavy-lifting of having to rework or minimize the narrative into a workable story for the screen, and reap the benefits. Hell, the initial plan was even to have Lugosi star in the film as The Monster, with Universal going so far as to immediately draft up some very early marketing materials, slapping Lugosi’s name at the top of posters.

It was a cash-grab, pure and simple. But then a gentleman by the name of James Whale became involved with the production and it became something else entirely.

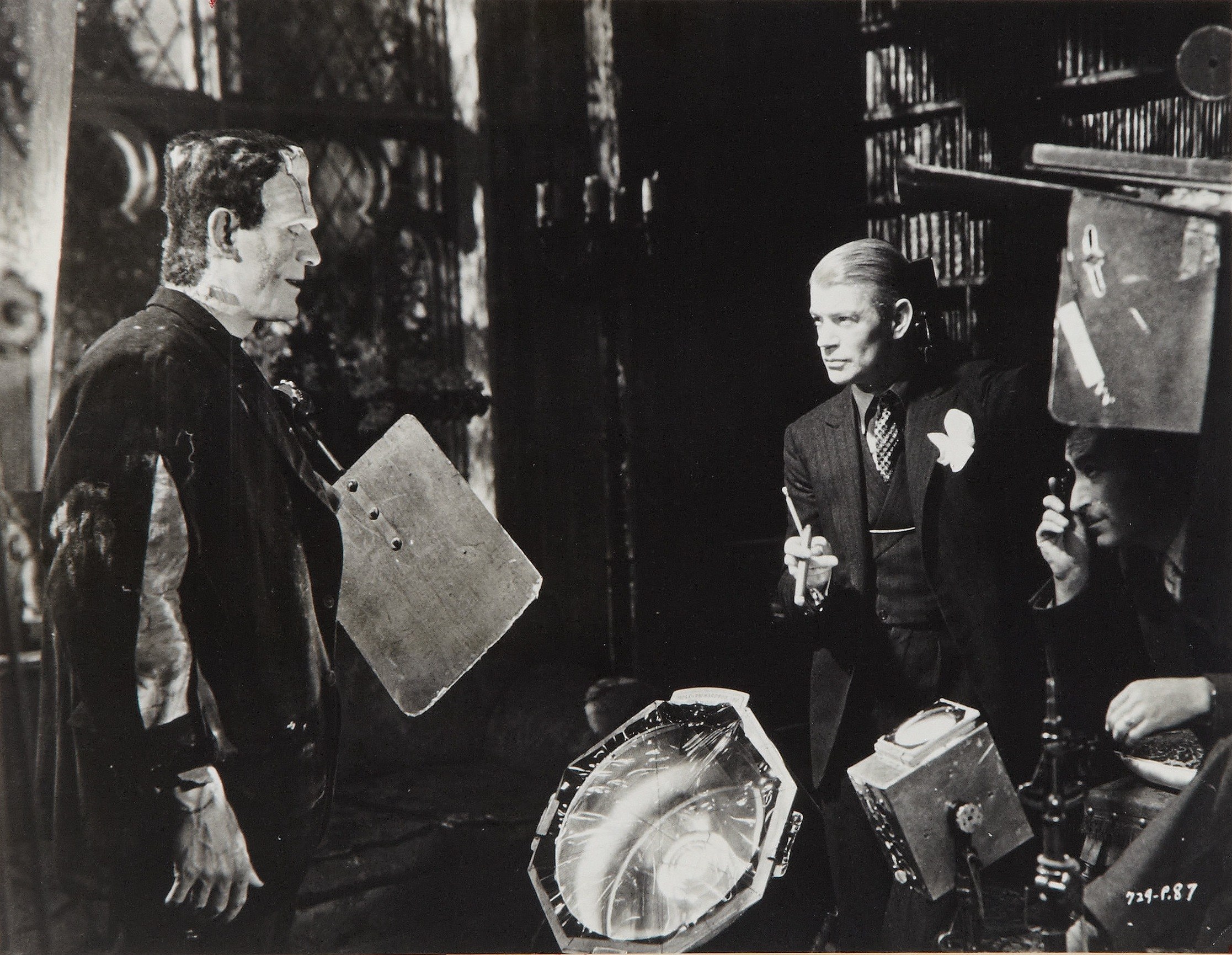

Whale was already an established, successful director at this point within Universal, thanks to the success of his prior film, Waterloo Bridge. As a result, Laemmle Jr. had pretty much given him free rein to pick whatever project he wanted to work on next, and when Whale found out the studio had purchased the rights to Frankenstein, he immediately became interested. Whale went on to work with several screenwriters (both credited and uncredited) in an attempt to revise and refine the script. The original stage-play script had called for The Monster to largely be a mindless killing machine, completely lacking the nuance and empathy the character had had in Shelly’s original novel. Whale, however, felt this was the entire crux of the narrative and tirelessly reworked the story so as to get something that was both feasible in terms of production and closer to the heart of Shelly’s work.

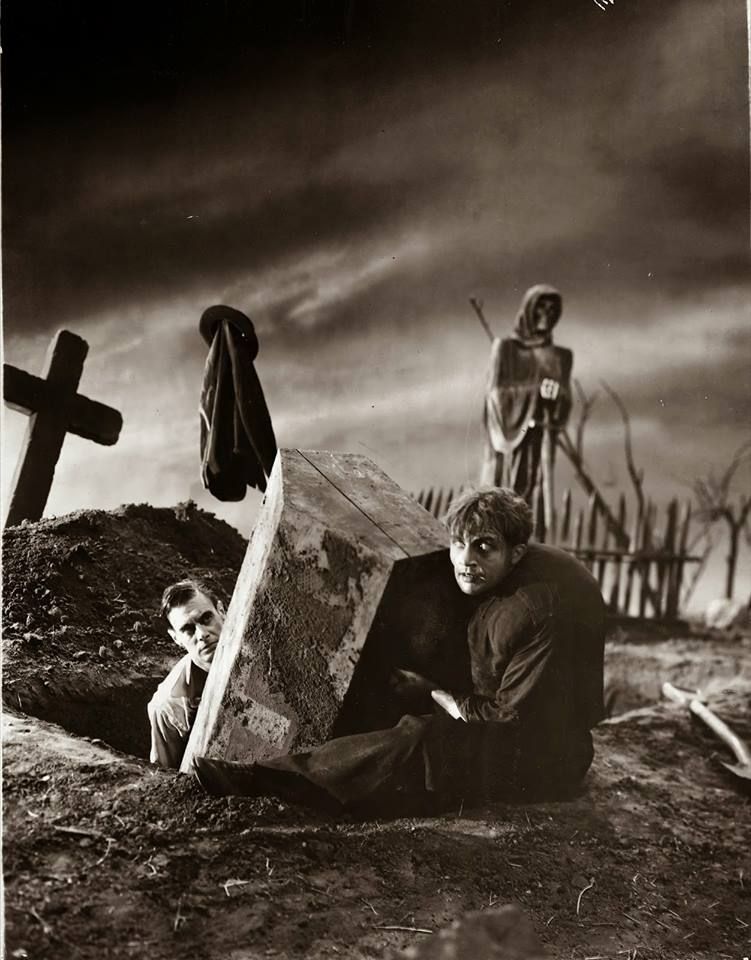

If Dracula laid the foundation of the cinematic language of modern horror, then Frankenstein built the monolithic gothic mansion that stood upon it. From the very first shot of the film, Whale vividly brings his new world of gods and monsters screaming into existence. As the opening shot pans across the burial scene, the set design, sound design, and cinematography all imply a world beyond the walls of the frame. Throughout the film, Whale and cinematographer Arthur Edeson utilize these fluid camera moves to not only bring dynamic movement and depth to their visuals, but also to remove the perceived walls of the form itself.

The camera moves between the walls of sets without a cut. Entire action beats are shown in one wide master shot, rather than cutting in for emphasis. You can practically feel Whale’s vital awareness of the limitations of the still-young cinematic form, and you can see him masterfully pushing against them and succeeding, with these visionary moments of innovation.

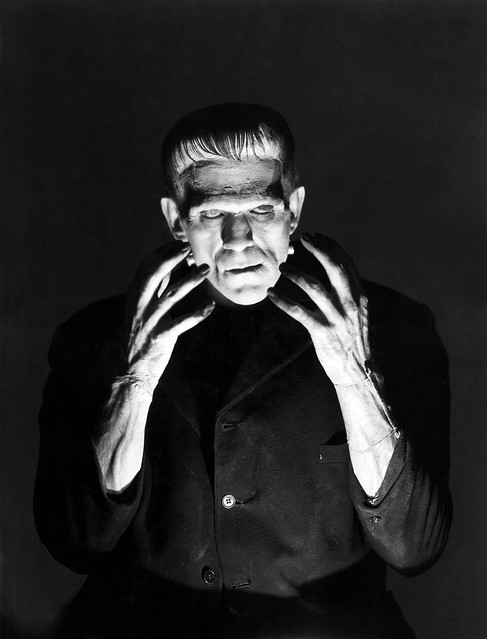

A moment such as The Monster’s introduction, wherein the edit violently and jarringly cuts to progressively closer shots, invading the audience’s space and forcing them towards The Monster’s face, demonstrates precisely how both acutely aware and completely in control of the artform Whale is. Elsewhere, the shot of Karloff’s Monster first being exposed to sunlight and grasping so desperately at it is utterly heartbreaking, not only because of Karloff’s ingenious performance, but also because of Whale’s firm grasp on the medium; he’s able to distill film as an art down to its most basic qualities (light and movement) and create something truly heartbreaking out of it, both within the film’s narrative and as part of a larger meta-narrative.

Choices such as this go well beyond redefining horror cinema; they see Whale and co. helping to redefine the perceived limitations of cinema itself. It is this innovative spirit and meta-awareness of its genre that have allowed Frankenstein to age so gracefully. Over the decades, like the finest of wines, Whale’s film has only gotten better.

Part of this is no doubt thanks to the fact that even as its audience inches closer to being a full ninety years removed from the film’s debut, the ripples of its impact seem to only grow clearer with each passing year. You can see it in its pioneering use of the kind of suspense techniques Hitchcock would use to craft his entire filmography decades later, in Karloff’s beat-for-beat perfect performance which endears itself to every child who sees the film, in the heady and ahead-of-their-time themes of religion and the cavernous nature of man’s best intentions, in the unprecedented use of visual motifs such as Karloff’s hands or fire to nail these themes home. Frankenstein is the ultimate fable, the kind of work that grows more prescient and relevant even as its audience grows further removed from its inception.

Frankenstein went on to become the highest-grossing film of 1931. It was also widely praised by critics and audiences, even those who hadn’t adored Dracula. It catapulted both Whale and Karloff to a level of stardom and success they had never known, instilled in Carl Laemmle Jr. and Universal that horror was a goldmine waiting to be plundered, and cemented the genre’s place in Hollywood history.

And yet, 1931 was still not done giving. Tune in next week for the final installment of our 1931 series, where we look at the lasting impact of the first-ever horror film to win an academy award; Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.