The year is 1931. The country is still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression. Dust storms are ravaging the once idyllic prairies and farmlands of several U.S. states. Prohibition is still two years away from being overturned, leading to riots and unrest. Thomas Edison, one of the very last remnants of the innovative and hopeful country the U.S. had been throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, dies.

The United States of America is a nation in flux, facing challenges on their own soil, the likes of which had never been seen before. Along with this tumultuous period of history, however, comes great art and the emerging prominence of a brand new genre of filmmaking: horror.

In the interest of not being disingenuous, it must be noted that this was far from horror’s birthplace. Cinematic pioneers such as Georges Méliès and the Lumière Brothers had been crafting short films that tapped into the primal power of horror in one way or another as far back at the 1890s, with works such as Le Manoir du Diable and Le Squelette Joyeaux. Throughout the 1920s, boundary-pushing and trail-blazing German expressionistic films such as Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu originated the form and language of what a full-length horror production could be. Meanwhile in the states, films such as John S. Robertson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and the Carl Laemmle-produced Universal films The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera were among the very first of what could be traditionally referred to as ‘monster’ movies, with the latter two originating the term ‘Universal Monsters’.

These films of the silent era were all crucial stepping stones, the formative first steps of a genre building itself from the ground up. Wiene witnessing Méliès’ Le Manoir du Diable and building off of its gothic aesthetic and cinema-of-attractions sense of wonder at its own macabre subject matter. Murnau witnessing Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and repurposing its calculatedly impressionistic designs into a wider visual world, full of depth and dynamic contrast. Producer Carl Laemmle at Universal Pictures witnessing this surge of innovation being poured into this new genre and the resounding success it was being met with across the globe. He believed in the genre and it’s potential so much that he urged the infamous conveyor belt of directors working on Phantom to keep pushing boundaries, resulting in the utterly entrancing early use of color in the masquerade sequence.

All of this to say that even prior to the innovation of sound with 1927’s The Jazz Singer, the horror genre was there, festering just beneath the surface. But it was in 1931, with the full power of sound and cinema at their disposal, that the horror film truly came of age, with the release of three horror films that changed the genre forever.

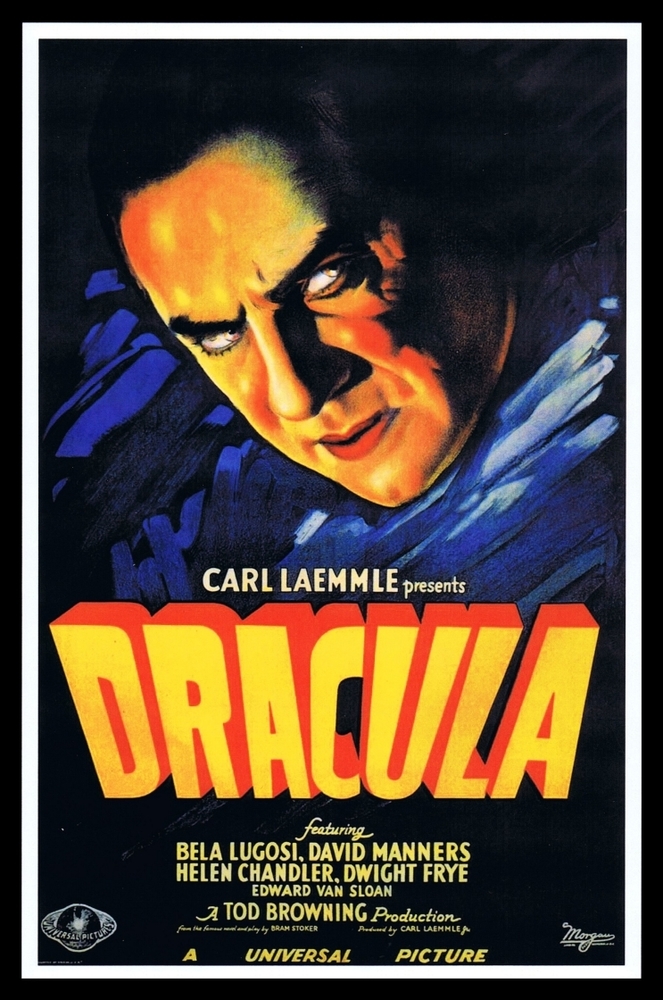

The first of these was Tod Browning’s Dracula.

Released by Universal Pictures and produced by Carl Laemmle Jr., Dracula remains an invaluably important milestone for the genre as it was the very first horror film to be made with sound. While this added another layer of texture with which to immerse audiences in the world of Transylvania, it also presented an entirely new set of challenges for the filmmakers.

Whereas a film such as Murnau’s Nosferatu had practically mastered the art of the silent horror film, Browning faced the difficult task of translating what had worked about those films into an entirely new cinematic language. Where Nosferatu used sparse title cards and the physical movement of the performers to convey information, the makers of Dracula had to figure out how to express such information through dialogue in a way that was both effective (i.e. conveyed the information the audience needed to understand) and efficient (i.e. didn’t lose the audience’s attention-spans).

For guidance on this, Browning and Laemmle Jr. astutely turned their attention to another medium of entertainment that had been dealing with such challenges for decades: the theater. The choice wound up working two-fold; for as interested as Laemmle Jr. was in bringing Bram Stoker’s gothic literature classic to the big screen, the sprawling narrative was going to require considerable condensing in order for such a production to even be remotely feasible. Thus, studying and eventually adapting Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston’s stage-play version of the story both allowed the creators to get a firmer grasp on what exactly a talking horror picture could (and should) be, while also giving them a pre-existing adaptation of Stoker’s novel which traded the epic bombast out for a more intimate tale of horror.

The choice to pull so much from the stage-play also resulted in one of the best pieces of casting in horror cinema’s history; Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula himself. Lugosi had risen to prominence as the character in the 1927 Broadway revision of the play and from the film alone, it’s easy to see why. It is again, crucial to note the positively herculean challenges Browning and Lugosi faced in crafting a version of this for the screen. Whereas masterclass performances such as Max Schreck in Nosferatu or John Barrymore in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were rooted so wholly in physical movement and precision, Lugosi was going to have to utilize an entirely different set of muscles and develop an entirely new set of skills in order to make the cinema’s first talking horror villain, Count Dracula, half as memorable.

And to Lugosi and Browning’s immense credit, they pulled it off.

The resulting film was not only a resounding financial success but an artistic one as well. Browning and cinematographer Karl Freund brilliantly build upon the work in the genre that had come before there’s, creating a visual language that, especially in the Transylvania-set prologue, feels utterly masterful. The way Freund utilizes sparse lighting to highlight Lugosi’s piercing gaze, the gritty inserts of rats and slugs crawling around in the filth that Browning cuts to as Dracula and his wives are emerging from their coffins to create an utterly unnerving mosaic, the integration of gorgeous matte paintings and stunningly realized sets to make the world of the film so tangible.

Once the film gets to the London-set portion of its narrative proper, what it loses in terms of sheer stunning production value it more than makes up for with its precise tension-building. Any number of sequences set inside the sanitorium revolve exclusively around dialogue and yet, thanks to the air-tight script and Browning’s firm grasp of the shifting power dynamics throughout and his ability to convey that in his visuals, they are able to reap more suspense out of it than most million-dollar setpieces of the modern-day.

Which is to say nothing of the performances. The entire cast is incredibly solid, with a notable highlight being Universal mainstay Dwight Frye delightfully chewing the scenery as Renfield. But of course, the main attraction is Lugosi, and from the first moment he steps on screen, he is instantly iconic. There’s a reason that all these decades and hundreds of different takes later, the predominant idea of the vampire in pop culture remains Lugosi’s interpretation of Dracula.

Dracula built upon the foundations laid by the films that had come before it to craft a finely-tuned, ideally-realized vision of what the horror genre was and could be in this new age of cinema. But as we’ll soon learn, 1931 was still far from over…

Come back next week to see how Browning’s Dracula set the stage for Universal’s other 1931 masterpiece; James Whale’s Frankenstein.