Hey there, fearless readers. Welcome back to the literary O.R. Last time we were here, we lost someone. There was nothing to be done, The Dark Intercept presented with severe symptoms, lackluster characters, and unconvincing motivations. The scenery was pretty but, alas, a handsome corpse still rots.

Let’s hope for the best this time. Our patient today is Artemis by Andy Weir. Scalpels ready, let’s begin.

Artemis is one of those books that’s been oft looked for, the long awaited sequel to Weir’s massively popular debut novel, The Martian. That book was a phenomenon. An unnatural force that broke through bookstores and readers like a vortex. The sort of story led by Gmork: the demon wolf. A tale that became an immediate part of our cultural landscape and changed the industry.

Weir is the indie writer’s wet dream. It would be an insult to call him an overnight success, even if that’s how he seems. He spent years writing, honing his craft, doling out stories for free on the internet. Which is the modern writer’s equivalent of busking on a street corner for pocket change. He tried to get in through the gates and was told, as so many of us are: no thanks, we’re not buying what you’re selling. So he gave his story away for free, and then for pennies. And so many people wanted that story that the gatekeepers came crawling to him. He ended up with a publishing contract, a movie adaptation directed by Ridley Scott, and correspondence with Buzz Aldrin.

Those are the sorts of rewards that causes a genie to nod their head in respect.

So, when word hit the streets that Weir had a new novel coming out, everyone’s ears perked up, at least mine did. There was obvious excitement mixed with a sort of morbid curiosity. The expected desire to read whatever Weir was dolling out next, but also the wonder at whether he could bottle lightning again.

So I cracked the pages of Artemis with the sorts of anxiety that accompanies the peak of a roller coaster. This is probably going to be wicked fun, but, also, I might die. What happened was somewhere in the middle. Artemis is like riding a roller coaster at three-quarter speed. Which isn’t to say it isn’t fun but it lacks the kinds of excitement and palpable danger I was expecting and hoping for.

While Weir’s first book took us to the Red Planet, his second takes us closer to home. The titular city, Artemis, is located on the moon. Our protagonist, Jasmine “Jazz” Bashara, has lived there, with her father, a well respected and successful welder, since she was six. Now, in her mid-twenties, she’s a porter, transporting packages to the wealthy elite who call Artemis home and to the tourists who’ve come for a visit.

Jazz is everyone you’ve ever met. She has big dreams and massive potential, but lacks the drive to fulfill either of them. She’s the ninety-nine percent, and she just so happens to live on the moon. Like most of your friends who are less successful than they should be, she has a side hustle, smuggling controlled items from Earth to the people on Artemis with the means to acquire them. Nothing heavy, no weapons, no drugs. Usually cigars, controlled because of Artemis’ oxygen rich atmosphere and propensity to not play well with fire.

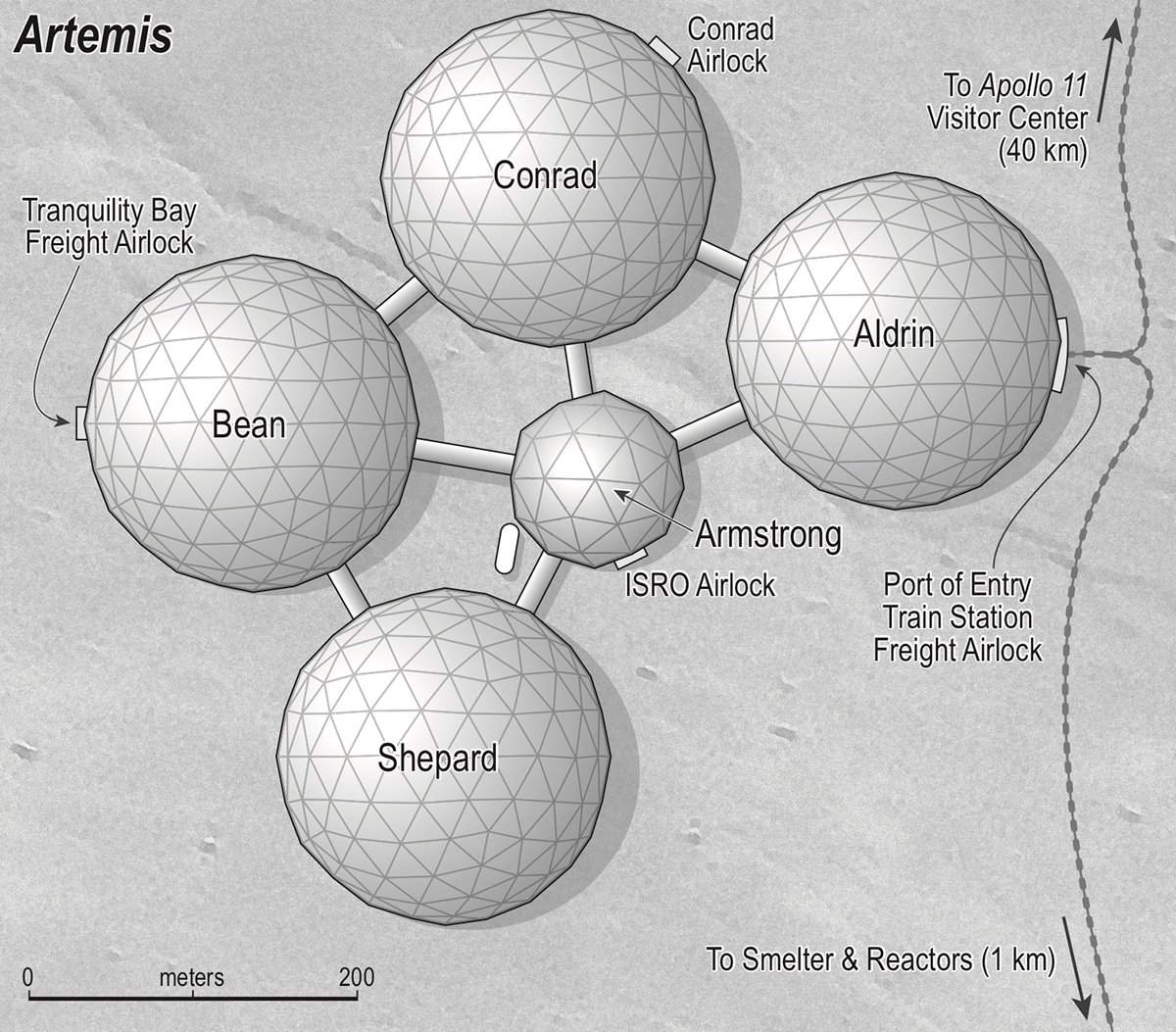

The city of Artemis, located near the Apollo 11 landing site (it is a tourist destination after all) is comprised of five domes named after famous astronauts. Jazz lives in one of the lowest levels in one of the dingiest parts of town. Her digs are little more than a closet with a cot. She’s angling for a job with the EVA guild giving tours to the tourists, a gig that would increase her income dramatically, but she can’t pass her test. Instead, she scrapes by with barely enough slugs (moon money) to keep her head above water and swimming in reconstituted booze.

That’s why, when she’s offered a million slugs by one of her regular customers to sabotage a moon-based aluminum mining operation, so that he can swoop up the contract, she says yes.

This is outside Jazz’s wheelhouse. She’s a low level criminal, the kind of crook the law mostly turns a blind eye to, but the money is too good to turn down. As is to be expected, her plan doesn’t go off without a hitch and Jazz gets wrapped up in a tightening circle with nowhere to run.

This is where Weir shines. It’s what made The Martian so much fun and it’s what makes Artemis worth reading. He has a talent for putting characters in compromising situations and forcing them to think their way out of them.

It’s clear that Weir has a love of science and puzzles. When his characters are solving problems, like how to light a welding torch in a vacuum or how to open a security enforced airlock from outside, his writing is delightful. He’s got a knack for making the details of physics, chemistry, and engineering entertaining that would make Bill Nye blush.

But there’s something about Artemis that causes those high stakes situations to lose more weight than the moon’s low gravity accounts for. The Martian painted a picture that was easy to see and a situation we could all easily imagine. While it takes place in a near future, not yet realized, when Mark Watney found himself stranded on Mars, we were all one of the billions on Earth who could only watch and hope that he came home. It had the benefit of feeling like a real situation with real consequences, a future that might be just around the corner. Artemis is a little more fiction and a little less science, and the story suffers for it.

Weir brings the same wit and the same love of details but it never quite feels real enough to lurch your stomach when things go wrong. It is, perhaps, unfair to compare Artemis to Weir’s earlier work, but it’s similar enough in tone and content that it’s difficult not to.

It is worth noting that Artemis gets full marks for inclusivity in characters. It checks all the right boxes. You have a strong, if flawed, female lead, representation from cultures around the world, characters that cross the sexual orientation spectrum, and all of them feel real. There isn’t a caricature among them. While some will undoubtedly interpret that as pandering to political correctness, they’d be wrong. Artemis is painting a picture of the future, one that includes a city on the moon which requires at least a modicum of international cooperation. When writing fiction, especially fiction that takes place in our world, any choice you make about the structure of that world is a political one. And Weir paints a world that, while still broken, has mended some of its current ills.

Artemis is, at the end, a lot like its lead character: competent, full of potential, and quite a lot of fun, but living inevitably beneath the shadow of its more successful and more beloved predecessor.

Scalpels down.

Cassidy is the author of The Staircase and releases short stories every month on Patreon.