The following is a guest post by Aldo Gomez.

On the evening of April 5th, 2018, the world lost famed anime director and Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata at the age of 82 due to a battle with Lung Cancer. While not as synonymous to the Ghibli brand, Takahata is just as important and influential as his business partner, Hayao Miyazaki, when speaking about the mediums of film and animation, all a person must do is to look at his library of work.

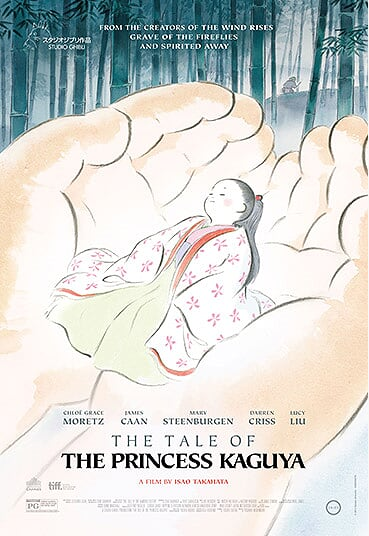

Takahata’s directorial filmography as part of Studio Ghibli only makes up 6 of the studio’s 22 feature films, but his works are the ones that stick out the most from the status quo; from the depressing anti-war film Grave of the Fireflies to the slice of life comedy My Neighbors the Yamadas, but his last film is the one that most exemplifies his out outlook on storytelling, culture and animation; The Tale of the Princess Kaguya.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is the last film written and directed by Takahata and was released in Japan in November of 2013, though it is an adaptation of an old Japanese folktale more commonly known as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter.

The following contains spoilers for the film The Tale of Princess Kaguya, if you haven’t seen the film it is available in physical format.

Princess Kaguya is a 16th century story of a village bamboo cutter that one day finds a small baby inside a stalk of bamboo, he and his wife take the baby as their own and raise it, but as the baby grows they come to find her to be more special and believe her to be a princess. Her adoptive parents groom her for royalty and to be wed, and to find a suitable groom Kaguya sends her suitors in search of impossible items. The princess eventually remembers her place among the celestial gods and accidentally beckons to the moon to return her to the heavens. Kaguya reveals the truth to her parents and returns to her humble small village to tell her childhood love the truth and that she wishes she could stay. The next full moon arrives and Kaguya is escorted back up to the heavens and her memories wiped by her celestial brethren as she leaves her earthly life.

Takahata’s stories of choice tend to stray from the fantastical and instead focus on personal stories such as a brother and sister surviving a world war II firebombing, the nostalgia of a 27-year-old woman on a trip to visit her family in her childhood home, and the everyday happenings of a family living day to day as they fight for who controls the television. Pom Poko and Princess Kaguya stray from his story style, but Kaguya more so as it doesn’t present a necessarily happy ending, but not an entirely sad one either.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya uses an existing folktale to lay the foundations for a unique look at life through the lens of the princess herself and those who surround her. Her adoptive father begins as a humble bamboo cutter, happy with his wife in the village, but as he notices that his new daughter is special he begins to groom her for a life she does not want, becomes greedy and loses himself as he becomes a member of high society. Kaguya sees the suitors lie and embellish themselves to gain her favor even though all they know about her is that she may be beautiful, in comparison to her childhood friend, Sutemaru, a simple villager that only wanted to spend time with her. Kaguya herself struggles when she starts being trained to be a proper princess, a handler tries to keep her in place, she overhears the townsfolk ridicule her father, and she falls into a deep depression when soldiers start to die in search of her impossible gifts.

There is no happy ending to The Tale of Princess Kaguya, Kaguya, in a moment of desperation wishes to the moon to return to the celestial heaven, and while her father and suitors do all that they can to fight off the heavens and Kaguya pleads to say a final goodbye, her earthly memories are removed. No one is hurt, no one dies, but something is lost, Kaguya exits the bamboo cutter’s life as magically as she entered it. Her memories of earth are forgotten, but those on earth cannot possibly forget Kaguya and the life they built with her.

Takahata focuses more on the human element rather than the fairy tale aspect of the story, seemingly setting aside any moral or pleasant conclusion, he also ignores a lot of questions; what is the celestial kingdom that Princess Kaguya is from, why was she sent to earth in the first place, and who delivered the gifts the bamboo cutter kept finding? It’s all second place to the bonds and relationships built.

The Ghibli library tends to share a visual aesthetic keeping the movies close in a style established as early as Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, but Takahata strays from the standard to create a moving ink-brush painting with sparse backgrounds and a simplistic color palette. Takahata uses the emotions of the story and characters to alter the art, as the peaceful renditions of the village are drawn with more detail and colors in contrast to Kaguya running in anger and the line work becoming more erratic and jagged.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya strays from traditional fantasy storytelling and visual stylings, it’s intimate and full of mystery like life itself, and this is the piece of work that most exemplifies Isao Takahata’s personal directorial style.

was born on October 29, 1935 and worked with Toei Animation in the 1960s where he would eventually take Hayao Miyazaki under his wing before leaving and starting Studio Ghibli with friend and producer Toshio Suzuki where the three of them would help create an animation powerhouse and help cultivate talent for generations to come.

On top of Takahata’s Ghibli filmography, I recommend watching the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, it is a look at the studio as both Takahata and Miyazaki work on their films The Wind Rises and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya.