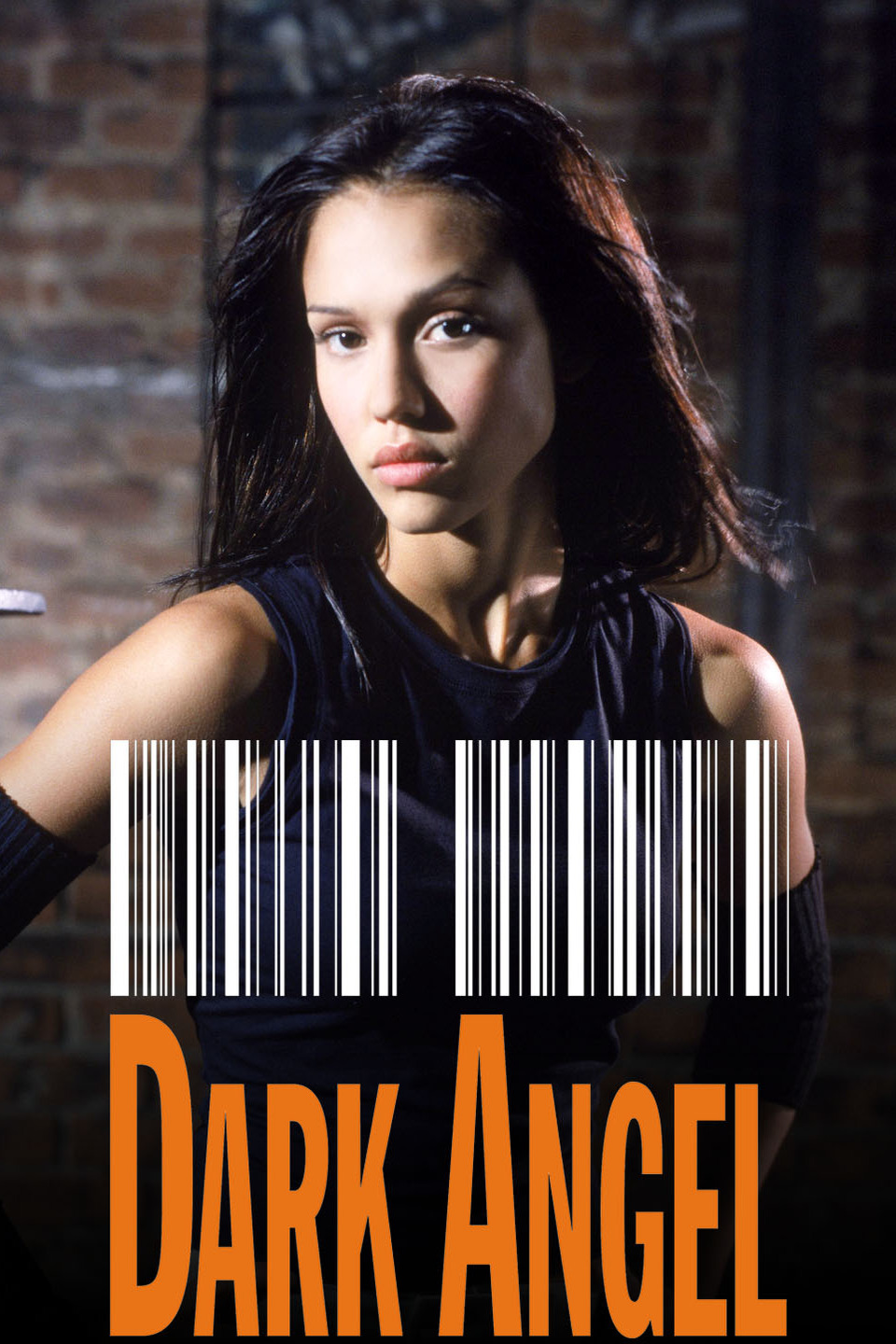

I have been waiting for 2019 since I was nine years old. On October 3, 2000, Dark Angel debuted on Fox and invited viewers into a world set nineteen years later: Seattle in 2019 as a dingy, broken-down city tightly controlled by corrupt police. It was a United States with police hovercraft drones but short on computers after terrorists detonated an electromagnetic pulse in 2009.

The nineteen-year-old protagonist Max Guevara, portrayed by Jessica Alba, was a genetically engineered super soldier who, as a child, escaped the facility she was raised in, along with several others like her who she considered to be her brothers and sisters. Ten years after her escape, the story followed Max’s journey to find her “siblings” while evading the military hunting them.

The world of Dark Angel was starkly different to most media I’d seen set in the future. Instead of prosperity, there was misery and desperation. Instead of awe-inspiring machines with the ability to perform near-miracles, technology limped to support a damned society without any hope of being saved. In cyberpunk fashion, some advanced tech still existed—Max and the other super soldiers, hovercraft drones, and social subcultures determined to blur the line between their humanity and the tech integrated into their bodies—but the more advanced the tech was, the worse the society that wielded it.

The world of Dark Angel was starkly different to most media I’d seen set in the future. Instead of prosperity, there was misery and desperation. Instead of awe-inspiring machines with the ability to perform near-miracles, technology limped to support a damned society without any hope of being saved. In cyberpunk fashion, some advanced tech still existed—Max and the other super soldiers, hovercraft drones, and social subcultures determined to blur the line between their humanity and the tech integrated into their bodies—but the more advanced the tech was, the worse the society that wielded it.

Dark Angel and its dark city was different from my small, quiet hometown. And as my family had only gotten a computer in 2000 when Dark Angel debuted, such a world seemed far away, but still within reach.

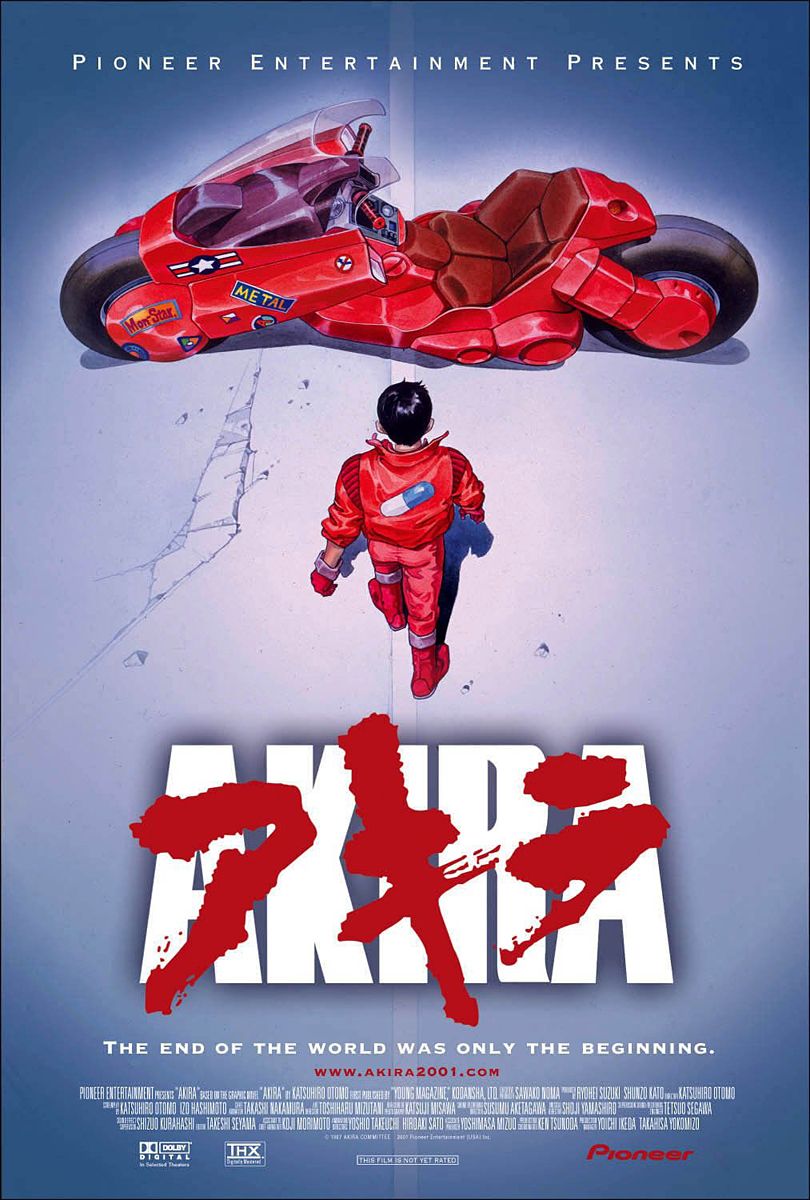

Like Dark Angel and 1982’s Blade Runner, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, a 1982-1990 manga and 1988 film,also envisioned a cyberpunk 2019. In Akira, Tokyo was rebuilt as Neo Tokyo after its 1982 destruction in World War III. Teenage Shotaro Kaneda led a motorcycle gang of fellow teenage delinquents as they clashed with other gangs, ran from police, and lounged in a school that barely taught.

Like Dark Angel and 1982’s Blade Runner, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, a 1982-1990 manga and 1988 film,also envisioned a cyberpunk 2019. In Akira, Tokyo was rebuilt as Neo Tokyo after its 1982 destruction in World War III. Teenage Shotaro Kaneda led a motorcycle gang of fellow teenage delinquents as they clashed with other gangs, ran from police, and lounged in a school that barely taught.

Akira emphasized the importance of motorcycles to these teenagers. Kaneda and his friends doted on their bikes with pride. As with Max in Dark Angel, riding a motorcycle within a city that had forsaken them allowed the protagonists a release and a taste of freedom. Yet, a motorcycle chase in Akira dragged its characters into a secret world of psychics, amoral scientists, corrupt politicians, and a military intent on peace at any cost. This clash triggers Tetsuo, Kaneda’s friend, into developing his dangerous hidden psychic powers, and the tension only escalates from there.

Though Dark Angel and Akira were created over a decade apart in different countries and inspired by different issues, threads of similarity run through both: anxiety over a world that seems both capable and intent on destroying itself, the hopelessness of the youth whose future is already damaged by those who came before them, and the indestructible perseverance of those who seek to survive and fight back against a crumbling world set on destroying them.

From both a relatively prosperous and peaceful United States in 2000, and a Japan in the 1980s still dealing with the aftermath of World War II and the atomic bombs, 2019 was far enough away that almost anything could have been possible.

Watching both visions of 2019 now in a post-9/11 world with wars that seem to go on forever, refugee crises, mass shootings, and too many tragedies and catastrophes to keep track of, I was struck by the unsettling similarities. Perhaps the anxiety of the young generation will always be present, but the generation of today seems more driven to cause societal change than those of recent history. As technology advances in our world at an exciting and alarming rate, its dangers and promises rise in equal measure. The ability to communicate immediately means word of happiness or discontent can spread like wildfire.

These days, bad news piles on us like a mountain of sewage that sweeps us into despair or else pushes us into rebellion. The same technology that allows the government and businesses to spy into our lives also lulls us into a privileged comfort that can make such an invasion of privacy seem like just another price to pay for prosperity and peace. But there is no widespread prosperity and peace except as a falsehood.

Small, divided pockets of society prosper while others suffer, and creators of advanced technology lead us in several opposing directions: advancement for its own sake, advancement for the good of humanity and our living world, and advancement for the sake of monetary gain even at the potential cost of a future.

Corrupt and selfish politicians and deadly police are a fact of life that we either resign ourselves to or rise up to rid us of. The desperation, fear, and anger of Dark Angel and Akira are disturbingly relevant, especially in the scenes of protests and social uprising, police brutality, terrorism, and the dejected and forgotten banding together.

Corrupt and selfish politicians and deadly police are a fact of life that we either resign ourselves to or rise up to rid us of. The desperation, fear, and anger of Dark Angel and Akira are disturbingly relevant, especially in the scenes of protests and social uprising, police brutality, terrorism, and the dejected and forgotten banding together.

Even the small but loud cults rang true. The more broken a society, the more desperate they can be for a savior, even if the brokenness is ill-informed, misdirected, or an entirely false narrative. The savior people seek, as in Akira, needn’t even be a true savior; the illusion of one is enough to spark hope or incite others to violence. In our world, cults are not as prevalent, but the mob mentality is. Powerful leaders and influential cultural figures easily stoke emotion within their followers, and our advanced technology allows their words to spread and their followers to act rapidly. The power of the word is all the more effective with vulnerability of fearful or worshipful people.

Still, both Dark Angel and Akira ended on somewhat positive notes. Before Dark Angel was cancelled, it left us with a cliffhanger of a Seattle on the brink of revolution, with humans and mutants working together to protect themselves from those who would oppress them. And the Neo Tokyo of Akira must once again rebuild from ruins, but it is a relief to evade the total destruction they came so close to.

Ursula K. Le Guin once said in her introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness that “science fiction is not prescriptive; it is descriptive.” Creators of science fiction cannot truly predict the future or tell us how things will be. They can only look at their own world and tell us how it might be, based on what is around them. Sometimes they hit the mark so close to home that it can feel like we were warned by a psychic, but it is only the work of mindful, observant, and perceptive creators, which make it all the more impressive.