Dave Chisholm’s ‘Instrumental’, is a meditation on devoting one’s life to art and what it takes to make it. The hero, Tom, is a solid, but not great musician. He meets a mysterious stranger who gifts him a old, battered trumpet. With the instruction to just play. However, once he starts using it, the deal carries a certain price.

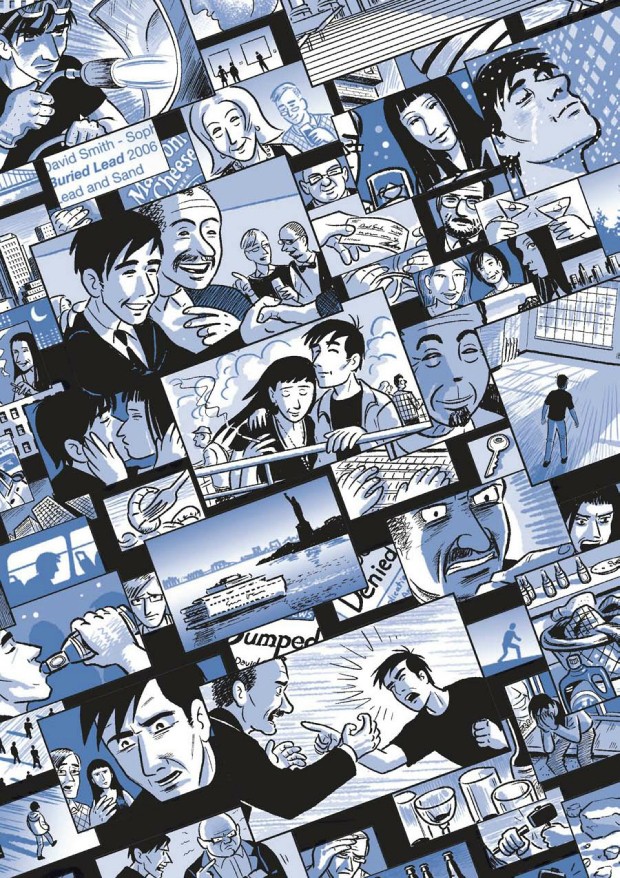

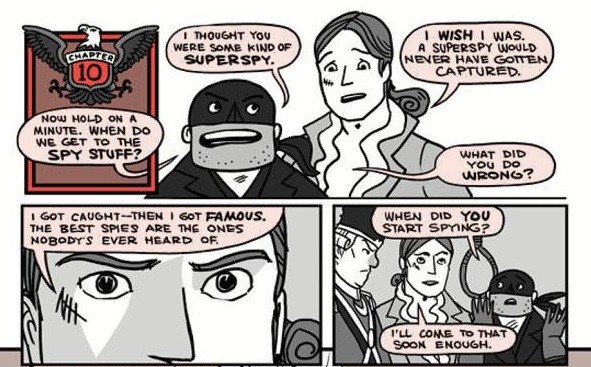

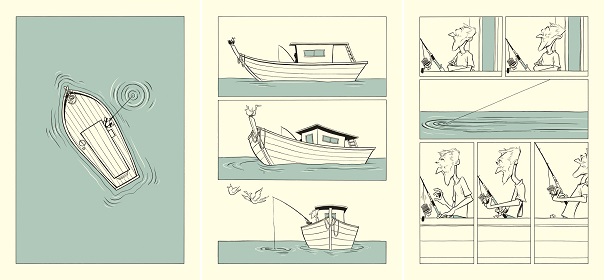

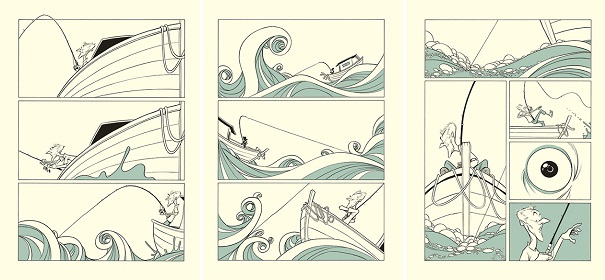

Bringing a virtuosic command of the language of graphic novels, Chisholm provides a story that is both touching with a strong sense of the inevitable woven amidst the fantastic. The angsty artist with a thirst for recognition is not a new character, but Dave flips the trope. I was regularly struck not just by the narratives details substantiating his description of the music world but the visual details that bring a metropolitan city to life; it’s not just the key phrases and visual attentiveness but the tone that made me feel like Chisholm is an insider and is telling the tale from a privileged perspective. ‘Instrumental’ is an art obsessed “Twilight Zone”-esque tale. It’s is one of those stories that takes a concept – in this case, devoting one’s life to art – and the story comes back, again and again, to examining that question from many angles.

Tell our readers a little bit about yourself?

I currently live in Rochester, NY, where I moved from Salt Lake City to get my doctorate in jazz trumpet from the Eastman School of Music, which I finished in 2013. I play music of various styles, teach music, and draw comics for a living. My life is strange but great!

There’s a lot going on in ‘Instrumental’, but how would you describe the big concept of the project?

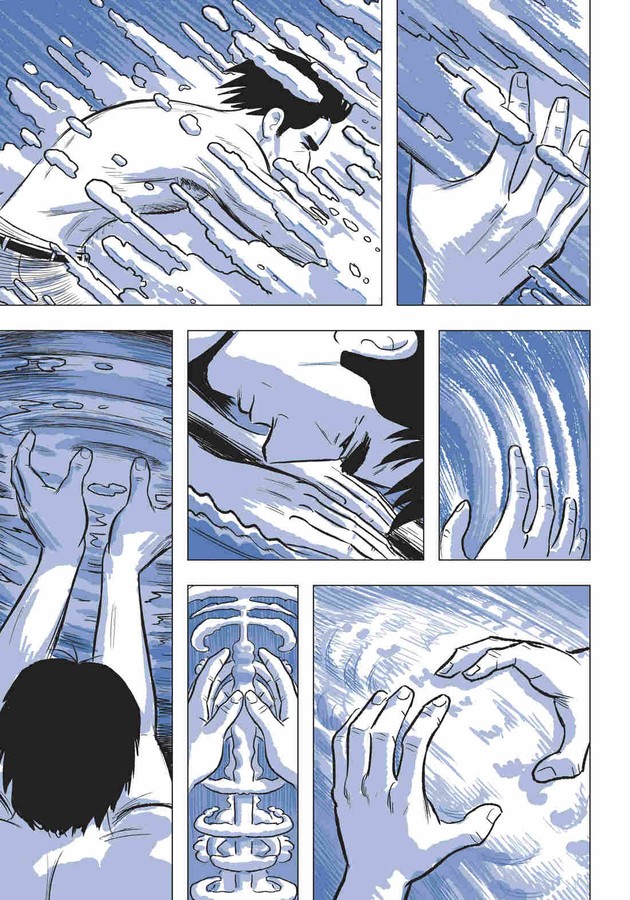

It’s a story about a lonely, angry young trumpet player whose career is flailing until he is given an old trumpet by a stranger after a gig. When he plays this mysterious horn, the music is incredible and he starts to gain fans–his future seems to be opening up. The only catch is that playing the horn seems to have unexpected side effects: when he plays it, maybe someone will die, maybe someone will disappear, or perhaps some other strange and possibly damaging things happen. The project is a 7-chapter graphic novel that comes with a free download of the 7-track full-length soundtrack. All of the music is new–the album turned out so cool.

So, why this subject and why now?

Gosh, “now” is an interesting term with this project. I started it way back in 2013 and mostly finished it in that same year. The subsequent years have been spent tweaking the project, fixing the script, adjusting the art and the mix, and waiting on finding a publisher and then for the publishing cycle to have room for such a project.

When did the idea of ‘Instrumental’ first come to you?

It slowly came to me over several years–at first it was towards the end of work on “Let’s go to UTAH!”, an idea about a trumpet that kills people. I sort of pieced together this simple story but it needed more intrigue. I had a few strange experiences here in Rochester that informed part of the story. While studying for the big 14-hour test at the end of work on my doctorate, I stumbled across a sizable chunk of music history that really felt like it fit with the story–all of these musicians somehow involved with some sort of esoteric, occult, or deeply spiritual or symbolic side of music. I knew that these musicians needed to appear in the story in some way. After finishing that test, BOOM I was off to the races and had a really strong routine. Every day I’d wake up and work from 7:30 to noon and from around 5-8pm. Scripting, thumbnails, pencils, inks, composing, recording, mixing, overdubbing, etc. It was an intense time–I was really lucky to have had a stretch with such copious amounts of free time. I started work on it on Feb 7, 2013, and finished the bulk of the work (writing, recording, mixing a 45m album and scripting and drawing 200+ pages) by mid December of that year. At least, to me, it was crazy.

What is it that made you want to tell this story?

Ah that’s complicated, I guess–a few things:

-A lot of the work is built as a message to myself. I make a lot of art and music and sometimes I lose track of what’s important. So much of Instrumental is about WHY we make art. It presents several viewpoints and they serve as reminders for me and hopefully other readers.

-I felt like, I guess I was at a spot where I was drawing well and was playing music at a pretty high level and it seemed like a great time in my life to try to make a really big work that combined these two streams that have carved out so much of my life. It feels like a landmark in my life–a culmination in some way. In a sense, as well, it presents a pretty cool marketing angle as well. I’m thankful Z2 saw it this way–I suppose there aren’t many people who could produce this kind of multimedia work!

What were you influenced by as you developed ‘Instrumental’?

While actually drawing it, I listened to a ton of Rolling Stones albums! Super random!

In other words, what would you say have been the main comics/film/literary influences on ‘Instrumental’? And your work generally?

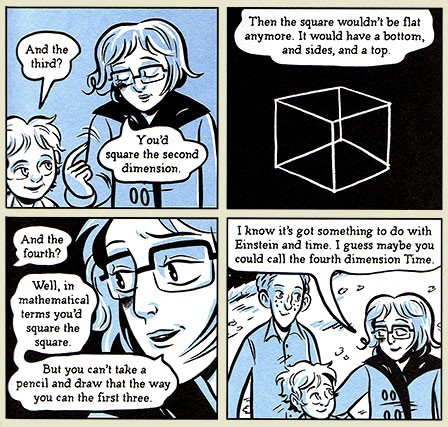

In terms of line, I really love comic artists who use a brush and have visible brushstrokes in their art. Paul Pope, Nate Powell, Craig Thompson, etc. In terms of storytelling, I think that Frank Quietly really sets the bar in terms of clarity and his innovative use of the camera. In terms of writing, I love Alan Moore–it seems like, with each project, he really sets up storytelling rules and sticks to them. In Providence, for example, the panel outlines change whenever something paranormal happens. Little details like that are all over the place in Instrumental: little storytelling rules that create a sense of “normal” that then create symbolic meaning when they’re broken.

Film influence: I think, at the time of drawing this, I was really obsessing over a few different films and directors. The movie “Drive” is so amazing and I love that there’s so few examples of outright exposition in the movie but it still manages to communicate so much visually. Also, the movies of David Lynch–how aggressively strange they are without explanation. Finally, “Midnight In Paris” by Woody Allen really sort of gave me permission to freely utilize figures from music history again without outright explanation.

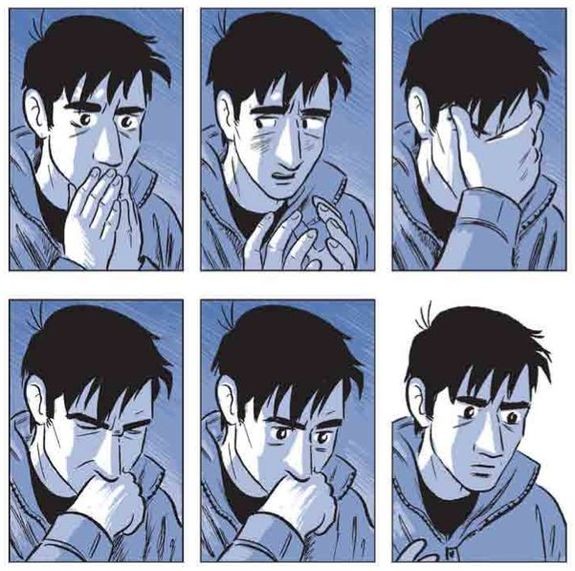

In addition to the big high-concept stuff, there are some beautiful small character moments. How long does it take you to find a kind of rhythm with your characters?

Since so many of these characters are based either on friends of mine or historic figures, it didn’t take much time although I did rewrite the first chapter probably 5 times until it was right. Tom is the one figure that’s not based on a friend so it was pretty tricky communicating his mental state at the beginning in a convincing way.

What’s been the most exciting part of working on ‘Instrumental’ so far?

The stretch of time when I was in the midst of working on it, frantically working so much 7-days a week, dreaming about these characters–that was an incredible time.

Did you do a lot of research for this project?

Yes, a fair amount. The appearances by WA Mozart, Hildegard, John Coltrane, Jim Morrison, and Alexander Scriabin are all filled with either direct or adapted historic quotes by those real-life figures. The history of trumpets that takes place in chapter 5 also took some time.

What made you publish ‘Instrumental’ as a graphic novel instead of releasing the chapters one by one monthly?

We toyed around with the option of releasing it monthly, but the chapter lengths vary too greatly and it starts off kind of slowly. I was worried that sales would be slow and we wouldn’t get to finish the story! The GN format is how I have always envisioned it.

Is there a conscious decision to decide which aspects of the book utilize which medium, or is it a more of an organic process?

It was pretty organic! I wanted each of the two parts to be able to convincingly stand alone but to combine to create something greater than the sum of the two!

Tell us about creating a mythology from scratch? Is it overwhelming?

Ha! Oh man. A lot of it for this was showing JUST ENOUGH to convince the reader that there’s this rich tapestry there…but honestly, it’s in your mind!

I mean, did you do any research into historical/mythological musical instruments? Can you recommend any books or authors that you found particularly compelling?

YES absolutely. Orpheus’ harp, King Tut’s trumpets, Shiva’s conch shell, Shofar knocking down the walls of Jericho etc. I dug and dug for mythological and historical examples that used music in some way. The main resource for the music history stuff is Taruskin’s 5-volume “Oxford history of Western Music.” Just so epic and entertaining. The book is KIND OF controversial in music-history circles because Taruskin is cranky and opinionated, but that’s what makes it such a fun and exciting read. Highly recommended but you should know something about notated music first…also the volume on the mid-to-late 20th C is sorely lacking in his treatment of jazz, rock, and popular styles. Other than that, it’s just mind blowing for a music nerd like me.

What is more challenging, writing and illustrating a 224 page graphic novel or composing and recording seven tracks of music? And Why?

They’re both hard and rewarding. I don’t know which is tougher. I guess the 224-page book is a pretty huge mountain of highly repetitive work, so that aspect of it separates it from the music recording, although my years of practicing the trumpet make almost every other time commitment in my life seem small.

Which one did you finish first?

First was a general outline of what happens in each chapter. Then I worked on both. The music was the last thing finished mainly because I waited to master the music until after I’d signed a contract with Z2!

There is still a lot of mystery surrounding the premise by the end of the ‘Instrumental’, could there be a continuation?

OH MAN it’s really only planned to be this one book and honestly it will probably stay that way. I have another story on the back burner that I’m planning on fleshing out this summer–totally unrelated to this one, drawing heavily from Inuit culture and mythology and set very far in the future.

‘Instrumental’ drops on May 23rd from Z2 Comics. Contact your local comic book store and get it! https://www.previewsworld.com/Catalog/MAR172272

OR…preorder it from Amazon https://www.amazon.com/Instrumental-Dave-Chisholm/dp/1940878152/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1490715086&sr=8-1&keywords=instrumental+dave+chisholm

For more information: https://www.davechisholmmusic.com/