In the late 1890s, when the advent of cinema was just beginning to take shape, film was primarily seen as little more than a cheap thrill. Even the Lumière Brothers, the makers of such iconic early short films as L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat or Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon, saw the art form they were helping to build as little more than a gimmick. Much like their fellow film-pioneering peers of the time, they did not make films for art, but rather as a means to an end. They would tour across the country with individual viewing stations where patrons could pay to individually watch a few minutes, at most, of film.

These earliest films were not anything extravagant in form, simply stationary shots of fairly mundane events happening, such as a train arriving at the station or workers leaving the factory. But to the public, it was hypnotic. ‘Moving pictures’ became something bigger than any of the earliest filmmakers and exhibitors could ever have dreamt of.

Decades later, this early period of filmmaking would come to be contextualized by film-essayist Tom Gunning as capitalizing on “the cinema of attractions”. Viewers flocked to these side-show film-fests, not for any sense of narrative or larger purpose, but rather to simply be entertained. Much like the circus acts and feats of strength these films were exhibited alongside, audiences were simply looking to be awed. As Gunning wrote at the time in The Cinema of Attraction[s]: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde;

“From comedians smirking at the camera, to the constant bowing and gesturing of the conjurors in magic films, this is a cinema that displays its visibility, willing to rupture a self-enclosed fictional world for a chance to solicit the attention of the spectator.”

Obviously, over the course of time, cinema has evolved a great deal. But elements of the cinema of attractions remains with us to this day. Audiences don’t flock to big blockbuster tentpoles for no reason; they’re looking to be awed. They want to see something they haven’t seen before.

But there’s one genre, especially, where the cinema of attractions has remained a vital part of the genre’s core DNA since the very beginning: the musical.

Perhaps no other genre is quite as thoroughly equipped and prepared to drop everything on a dime, in the name of awing the audience, as the musical is. This owes a great deal to the fact that, in their earliest form, musicals were positively rooted in this concept. In 1927, The Jazz Singer helped usher in an entirely new era of filmmaking in becoming one of the first motion pictures to have sound. In using this new element of sound to its full capacity, it was also the first musical ever committed to film. And while it was not without a narrative or other elements, it was first and foremost a piece of the cinema of attractions. Audiences turned out in droves to see a man talking, singing, and dancing on-screen.

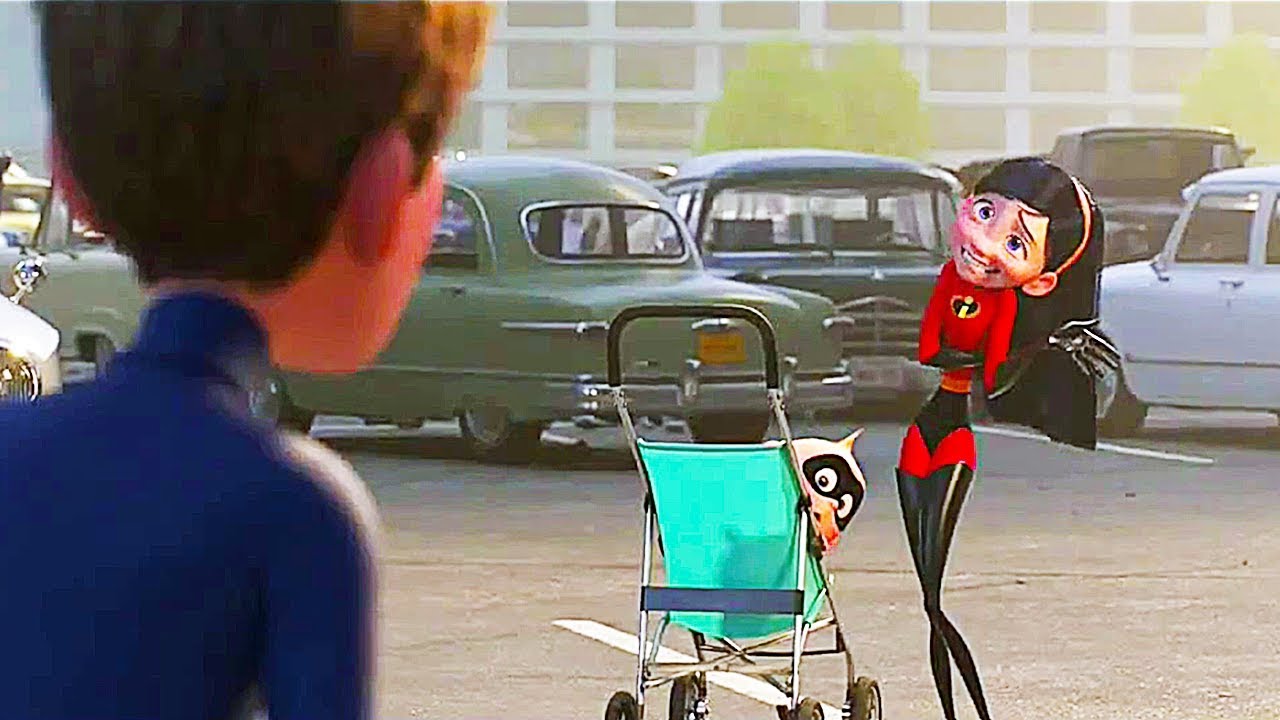

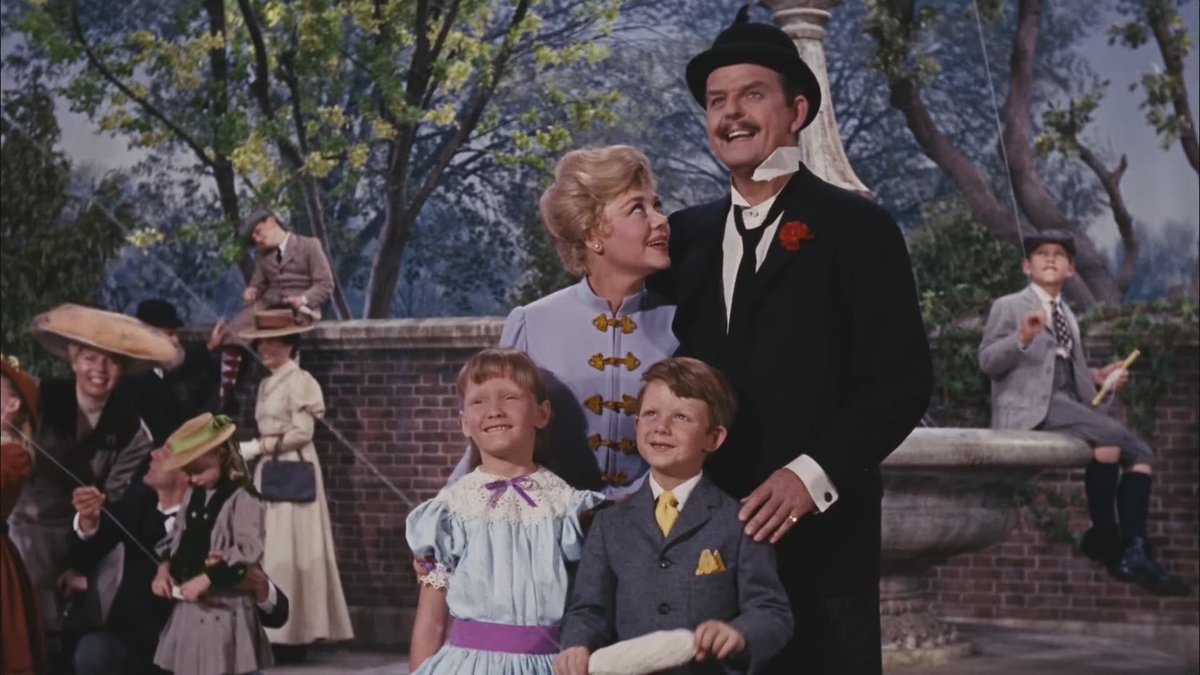

Over the last hundred years or so, there have been hundreds of musical films, each one of them indebted to the cinema of attractions in one way or another. But perhaps the most interesting of the bunch was a film that not only embraced the cinema of attractions through its formal elements but also made the conflict between early cinema and new cinema one of its primary narrative and thematic threads. That film, Walt Disney’s immortal classic, Mary Poppins, went on to change musical cinema forever.

Released in 1964, the film came four decades-deep into the prime of the Hollywood musical, and only a few years prior to the genre’s inevitable crash as the world stepped into the ‘70s. Just as westerns evolved from fairly straight-forward tales of good versus evil into more complex, nuanced, and mature stories in later decades, so too did the musical. By the fifties, classics such as Singin’ in the Rain were actively attempting to advance the genre beyond just simple song and dance routines. These films were still very much rooted in the cinema of attractions, delivering show-stopping musical sequences at every turn, but they were also actively striving to reach new heights.

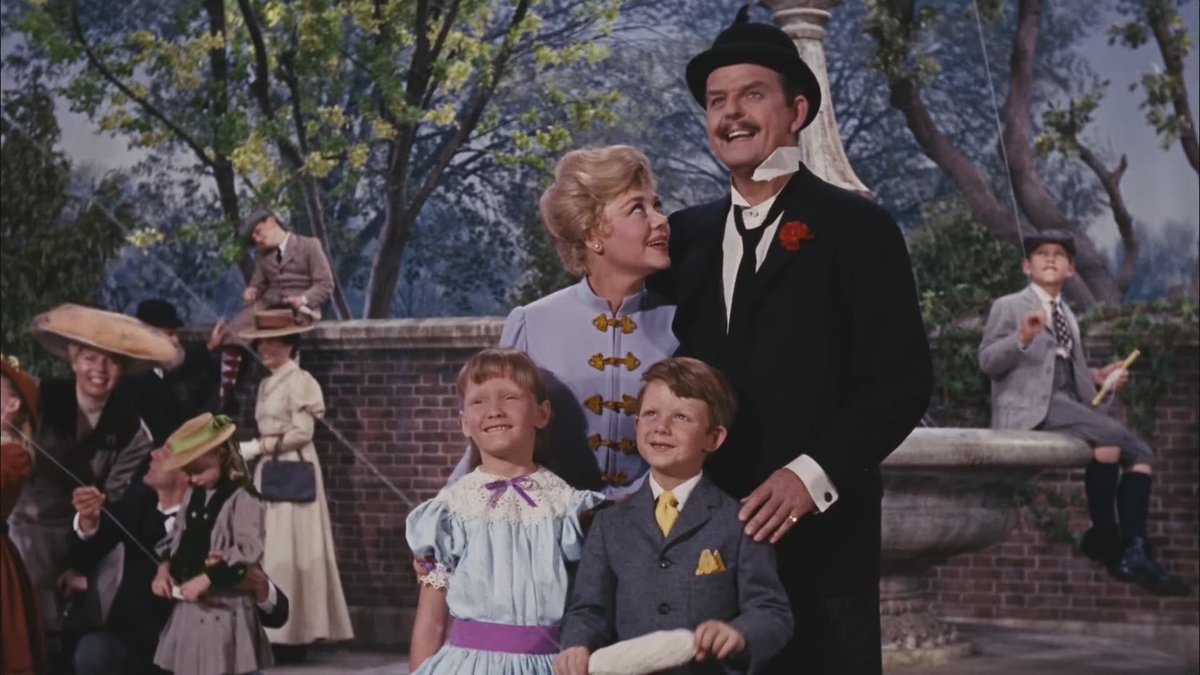

Mary Poppins was a culmination of all of this. Going above-and-beyond traditional song and dance routines in truly Walt-ish fashion, Mary Poppins was stuffed to the brim with not only phenomenal songs by the Sherman Brothers and visually striking dance sequences to match but also some of the most incredible visual effects ever committed to film. From the film’s revolutionary implementation of glass and matte paintings, to the extensively impressive wirework used to make characters fly, to the jaw-dropping chalk drawing sequence that mixed live-action and animation so fluidly, the film plays its effects off like an unbelievable magic trick to the audience.

The early moment when Mary Poppins first goes up to the nursery with Jane and Michael is a perfect example of this. As Mary reaches deep into her bag, pulling out objects that are far too big to be legitimately housed within the bag, Stevenson goes out of his way time and time again to rub the audience’s nose in what seems like the only logical answers. The table’s underside is clearly exposed to the camera, showing that there isn’t any larger bag beneath that she is reaching down into. The bag is moved all across the table, never staying in the same spot for too long, demonstrating that it isn’t attached. And most effectively of all, Michael goes from standing next to Mary to the underneath of the table, investigating for himself, all in one fluid shot. This is the cinema of attractions at its finest, presenting genuine magic on-screen for the audience and daring them to guess at how they could have possibly pulled it off.

And of course, it is, because that’s precisely what Walt Disney has always specialized in. He is arguably the biggest advocate of the cinema of attractions in all of history. From his first Mickey Mouse shorts, to his first feature film with Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, to Disneyland itself, Walt was all about awing his audiences. He wanted to immerse his viewers and guests in a narrative, absolutely, but he was also quick to prioritize maximum joy and wonder over these constraints time and time again.

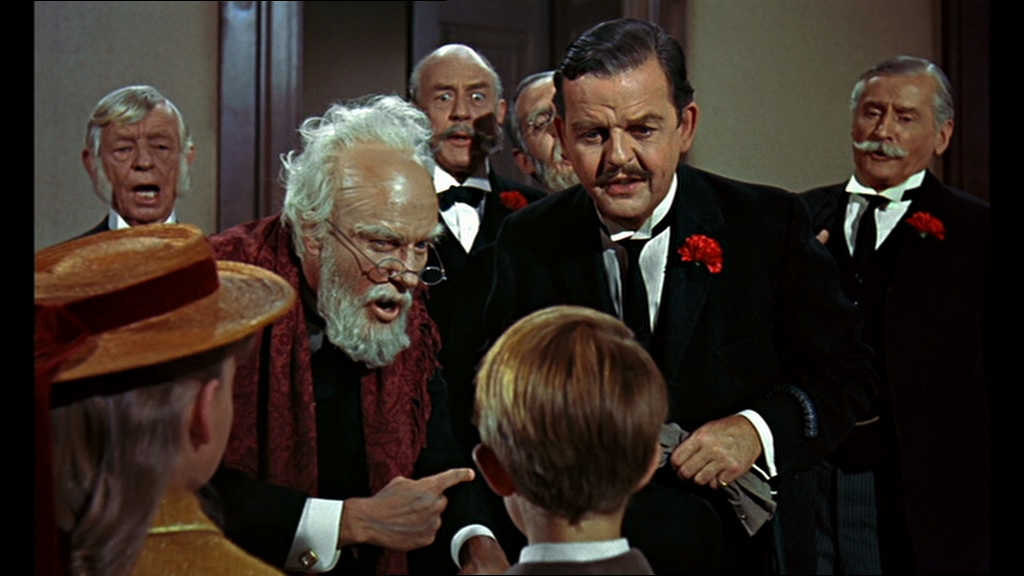

Which is what makes the thematic work of Mary Poppins all the more interesting. In the film, Mr. Banks is looking for a nanny who can help support a household founded on “tradition, discipline, and rules” and mold his children’s minds. Yet, when Mary Poppins is brought on-board, there is a fundamental break in their theologies.

As a character, Poppins’ entire ethos is to educate the children while also entertaining them. As she reiterates time and time again, “a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down”. As a result, she’s teaching the children valuable lessons about everything from cleaning up their room to respecting their elders, but all while taking them on magical adventures. This gives the film a somewhat episodic structure, with the first hour or so after Mary Poppins arrives being spent on these seemingly disconnected sequences.

For the narrative, these sequences are hardly necessary. They could be cut and the script could still maintain the same essential structure. But for the film, these sequences are everything. They are the beating heart of all Walt was then and was ever trying to do: entertain. Rather infamously, author P. L. Travers herself felt that the entire animated sequence was superfluous at best and begged Walt to cut it from the film. However, Walt refused, insisting that it was key to the film.

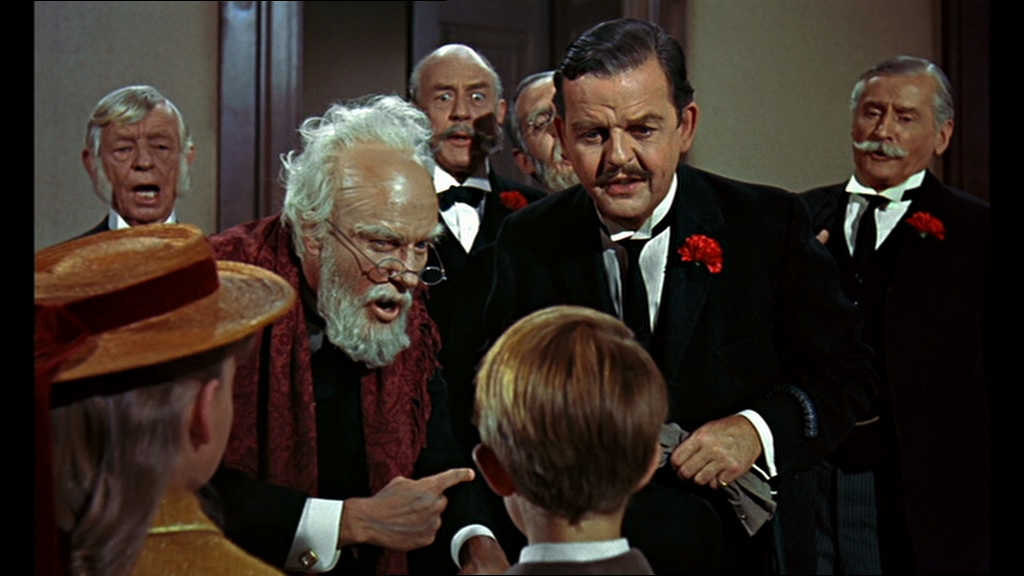

It isn’t hard to find the mirroring of this dynamic in the film, when Mr. Banks comes crashing back into the narrative, insisting that all Mary Poppins has done with the children since her arrival is indulge joyful frivolities. While it would have been easy to sell this conflict as thin and little more than a reference to some of the behind-the-scenes creative tension, it is so much more than that.

Mr. Banks serves as a representation of the rules of storytelling, insisting that Mary Poppins stay on-schedule and follow the rules. He views unnecessary singing, such as the impromptu renditions of Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, as unwelcome and aggravating at best. When the children want to invest their tuppence in feeding the birds, Mr. Banks and his fellow-bank workers insist that this is a ridiculous waste of their money and that they should instead do the reasonable thing and allow the bank to hold onto their money for them.

Much like the rules of narrative filmmaking, Mr. Banks views the world as something that will devolve into chaos if it is not rigidly structured. Anything outside of what is absolutely necessary is simply excess to him and has no purpose. But Mary, and to a larger extent the film itself, sees that sometimes that structure can be suffocating and that sometimes the chaos is where the real beauty of the world truly lies.

To say that the world must be constantly kept in rigid formation in order to function is to deny the presence of visceral, unpredictable magic in the world. Which, of course, is not a viewpoint that Mary Poppins or Walt Disney himself were ever going to ascribe to. The key difference is that while Mr. Banks sees magic as some ludicrous thing that must be explained, Poppins herself openly denies explanation. She is the embodiment of everything the cinema of attractions stands for; a character completely capable of breaking the rules of her own universe and narrative, so long as it heightens the experience of the viewer.

It is no coincidence that by the end of the film the freeform creativity of Mary Poppins has won out. She helps show Mr. Banks that not only do the children need more creative freedom and “sugar”, so-to-speak, in their lives but so too does he. Because in a world that is frequently shoving such large amounts of medicine down our throats, we all need a spoonful of sugar every now and then.

Disney’s Mary Poppins is a perhaps one of the greatest genre commentaries ever made. In foregrounding the inherent conflict in all musicals (that of the cinema of attractions versus narrative structure) in both its text and subtext, Disney was able to deliver a film that both explored the very reason why film ever came into existence in the first place. Tom Gunning coined the phrase cinema of attractions to illustrate what he felt was a parallel between cinema and the “attractions of the fairground”, saying;

“Such viewing experiences relate more to the attractions of the fairground than to the traditions of the legitimate theater. The relation between films and the emergence of the great amusement parks, such as Coney Island, at the turn of the century provides rich ground for rethinking the roots of early cinema.”

Which only makes it all the more fitting that the ultimate commentary on the subject’s prevalence in modern film was delivered by none other than the king of fairground attractions himself, Mr. Walt Disney.