The year is 1931. It is December, and James Whale’s Frankenstein has taken the world by storm. Coming mere months after the groundbreaking success of Tod Browning’s Dracula, Whale’s film’s resounding success has left audiences with a brand-new insatiable appetite for horror and studios scouring the countryside for any and every horror property they can get their hands on.

But as the rest of Hollywood, including Universal and Carl Laemmle Jr., desperately scramble to cash-in on this daring new fad as quickly as they can, one studio is eagerly, perhaps unexpectedly prepared: Paramount Pictures. And it’s all because of a man named Rouben Mamoulian.

By 1931, Mamoulian was already a bankable asset for Paramount, both artistically and commercially. His first film, Applause, released by Paramount in 1929, became an instant benchmark in cinema history. In a time when the all-new implementation of sound recording in cinema was forcing the directors of most talkies to stagnate their camera inside a sound-proof box, Mamoulian’s Applause featured extensive camera movement and groundbreaking implementation of sound as part of the expression of the art form. His second film, 1931’s own City Streets, was a critically-acclaimed noir film that also brought in similarly big business for Paramount. Following the wide-ranging success of these two genre-spanning films, Mamoulian could essentially write his own ticket at Paramount. And indeed, he did.

Two months prior to the release of City Streets in April, Tod Browning’s Dracula happened. In the immediate aftermath of Dracula’s success, Mamoulian pitched Paramount on the idea of dusting off the studio’s own piece of classic gothic literature; Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

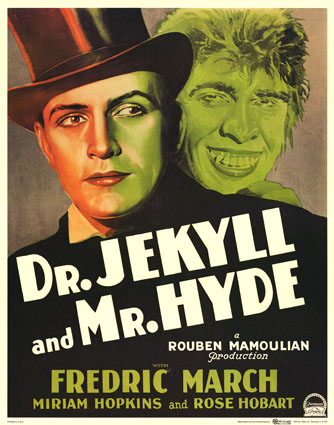

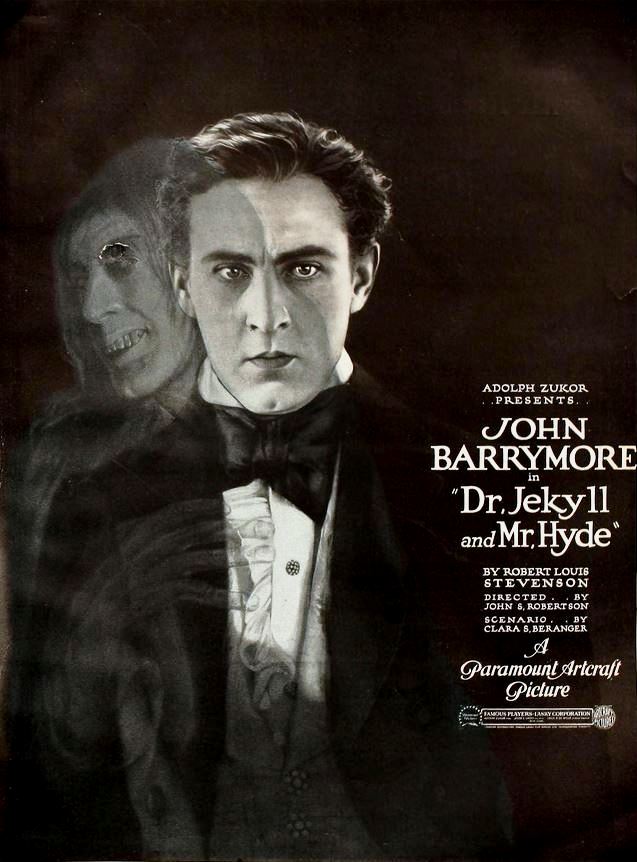

Paramount still held the rights to Stevenson’s novel after having purchased them in order to make the iconic John S. Robertson-directed silent film based on the material in 1920, starring John Barrymore. Mamoulian had, reportedly, long loved the Robertson film (so much so that he initially even sought after John Barrymore himself to reprise the title dual role), and Paramount was eager to throw their hat in the ring of this new cinematic trend. So when Mamoulian, two huge hits already to his name, approached them, Paramount positively jumped at the chance, immediately greenlighting the project with Mamoulian set to not only direct but also produce the film. And so, Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was born.

While the film’s genesis did have a great many similarities to the other films of the year, it also had some exceedingly intriguing differences. Whereas Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein films had both been largely based on pre-existing stage-play adaptations of the novels, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’s road to the screen was a bit more complex. For starters, whereas the original Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley texts were large, expansive pieces of literature with elaborate settings and setpieces that would have been nigh unfilmable at the time, Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella was short, concise, and intimate in its storytelling. The only problem with adapting the text verbatim was that Stevenson’s work hinged on a big, game-changing third act twist (the reveal that Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde are one and the same) that the entire audience now already knew the outcome of.

Thus, we can see the story slowly evolve across the history of its adaptations, each storyteller building upon the strides of the last. The first of these came in the form of Thomas Russell Sullivan’s 1887 stage-play, which was a mostly straightforward adaptation of the novella, though it put far less emphasis on the twist and far more emphasis on the character of Dr. Jekyll. Here, Sullivan made Jekyll himself the main character, as opposed to Stevenson’s novella which told the story from an outsider’s perspective. On paper, this may sound minuscule, but it’s a crucial change that every subsequent adaptation will build upon. From here came Robertson’s 1920 silent film, which preserved a great deal of the narrative of the stage-play, keeping new additions such as the Carews, but delved even deeper into making the piece a character study of Dr. Jekyll himself, exploring the depths of his depravity as Hyde in a fashion that remains sickening to this day.

Which brings us to Mamoulian’s version. For the scripting of the 1931 film, screenwriters Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath worked in conjunction with Mamoulian to craft a script that not only built on everything that had come before it, incorporating elements from each of the previous adaptations, but also recontextualized several of the most iconic setpieces of Stevenson’s novella, weaponizing them in entirely new ways. The results are staggeringly effective, giving the film a script so rapturously received that Hoffenstein and Heath were even nominated for an Academy Award for their work.

Building off of this script, the final product of Mamoulian’s film itself feels utterly revolutionary; a uniquely singular and harmonic vision from start to finish. With Mamoulian serving as both producer and director for the first time, he essentially had the final say about every single element in the frame and it shows. Each and every frame is brimming with an authorial intent that was practically unmatched in Hollywood at the time. It’s fascinating to watch as Mamoulian takes themes and motifs whose groundwork is established in the script and carries them over into his visual form, making them all the stronger and more poignant. Take for example the early line of dialogue in which Dr. Jekyll equates the invention of the fire-lit lamp post to his own scientific boundary-pushing; Mamoulian takes this idea and makes it one of the defining motifs of the entire film. Fire, whether it be in the form of candles, fireplaces, or a boiling pot of water, looms over Jekyll throughout the film. The first time Jeykll gives in to his desires and decides to free Hyde, it is visually punctuated with a shot of a pot of water above the fireplace in his lab, beginning to boil over. Later, the final shot of the film sees the camera returning to this same pot, the water all now but boiled out of it, framing Jekyll’s corpse in parallel to it.

Even the most minute details of set dressing, such as the juxtaposing black-and-white tiled floors or the paintings of regal, well-respected men, are actively working to strengthen the film’s core points. Mamoulian layers and brilliantly weaves this fascinatingly complex canvas of themes and motifs. From the flowers used to symbolize the innocence and love of Muriel Carew, to the use of cats and birds to symbolize the predator-and-prey relationship, to the consistent and impactful use of reflections to capture Jekyll’s internal struggle, it’s an intricate lacework of meaning that only grows more powerful with repeat viewings.

In bringing renowned cinematographer Karl Struss onboard the film, Mamoulian and he crafted a distinctly singular visual style for the film that remains decades ahead of its time. If Frankenstein saw James Whale pushing at the boundaries of cinema itself, then Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde sees Mamoulian bursting right through them. The opening shot of the film is an extended long-take, POV sequence in which Struss and Mamoulian further the thematic idea of each adaptation submerging the audience even deeper into Jekyll’s psyche in a very literal way; we’re literally seeing the world through his eyes. The result is an extraordinary technical achievement, the likes of which had quite literally never been seen before. You can practically feel Mamoulian and Struss beaming with glee as they invent entirely new kinds of camera movements and techniques, obliterating the understandings of what could and couldn’t be done with film as an art form, all in the name of further immersing the audience into Jekyll’s broken psyche.

This mantra can be felt all throughout the film, but nowhere more so than the brilliantly conceived transformation sequences. The use of one-takes, seamless editing, and mystifying lighting tricks results in some of the most stunning practical effects work ever committed to film, with the audiences being forced to watch Jekyll’s gruesome transformation into Hyde as if it is truly happening before their very eyes.

Of course, one cannot talk about the film’s legacy with speaking of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde himself, Fredric March. The entire cast is brilliant here, with Miriam Hopkins turning in a particularly powerful performance as Ivy Pearson, but March is positively transcendent in the lead dual role. He’s so good in it that he single-handedly elevated the genre to one that could be thought of as respectful and artistic, becoming the first ever actor in a horror film to win an Academy Award for their performance. And no doubt, a lot of that had to do with the showier bits of his performance; the groundbreaking camera techniques are ludicrously impressive during the transformation sequences but they would be nothing with March’s absurd commitment to the performance absolutely selling these moments. But some of March’s best moments come in the more subtle and reserved exploitation of the toll this kind of fractured mentality would take upon a man.

Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde had its world premiere on the final day of 1931, December 31. Between Hoffenstein and Heath’s brilliantly written script, Struss’ stark and instantly iconic use of the black-and-white form, Mamoulian’s incendiary unified vision, and March’s immediately groundbreaking performance, it was something even audiences who had just lived through Dracula and Frankenstein were unprepared for. The film was critically acclaimed and a huge hit at the box office for Paramount, continuing Mamoulian’s stunning streak of success.

However, there is a somewhat tragic turn for the film and its legacy. Some years after its release, Paramount sold the rights of the film to MGM, who then produced Victor Fleming’s perfectly serviceable 1941 film. Rather than continuing the evolution of the story, Fleming’s film actively stagnated such creativity. It was a beat-for-beat remake of Mamoulian’s and in order to avoid unfavorable comparisons between the two, MGM locked Mamoulian’s film away. It wasn’t until decades later, in 1967, that the film finally became available for screenings and study once more.

In those intervening thirty years, Dracula and Frankenstein cemented their legacies as bona fide pieces of horror cinema history. The characters of Count Dracula and Doctor Frankenstein’s Monster became synonymous with Browning and Whale’s respective films. The same cannot be said of Mamoulian’s film, because its initial chance to become legend in those crucial intervening years was unfairly stripped away.

The final word on the matter is this: Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a blazingly innovative, original, and groundbreaking piece of horror cinema. It may have been ‘lost’ for several decades after its release but it has more than earned the right to stand proudly alongside Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein as the films that changed horror forever.