In a nutshell, Dylan Dog is a comic book about a guy who fights monsters.

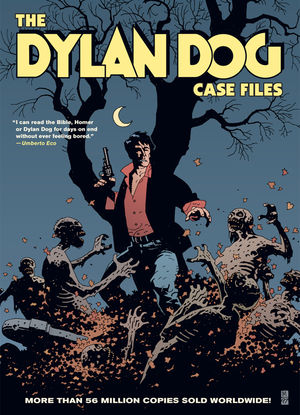

If that sounds intriguing enough for you, stop reading right now and go pick up THE DYLAN DOG CASE FILES (Dark Horse, $24.95). You won’t be disappointed. If you’re still not convinced, how about this: Dylan Dog is a comic book that in its native Italy is known to sell over a million copies per month (in comparison, the top American comic of September 2009, Blackest Night #3, sold a little over 140,000)? No? How about the fact that Umberto Eco, literary critic, philosopher, semiotician, and an otherwise really smart guy, likens its readability to that of the Bible and the works of Homer? Are we getting there?

Created in 1986 by writer Tiziano Sclavi for the popular publishing house Sergio Bonelli Editore, whose greatest successes to that point had been westerns (of which Tex is probably the only one familiar to American audiences, thanks to the recent involvement of Joe Kubert), Dylan Dog sprang almost fully-formed from the head of Sclavi (aptly aided by the artist Angelo Stano and cover artist Claudio Villa), with its unique combination of familiar genre tropes and touches of black humor and surrealism, and quickly established itself as a cult favorite. Published in the popular format of monthly 96-page installments drawn by a rotating lineup of artists, it steadily gained readership throughout the rest of the decade, eventually becoming Italy’s best-selling comic, and managing to capture the hearts and minds of critics and the country’s literary intelligentsia along the way, as well.

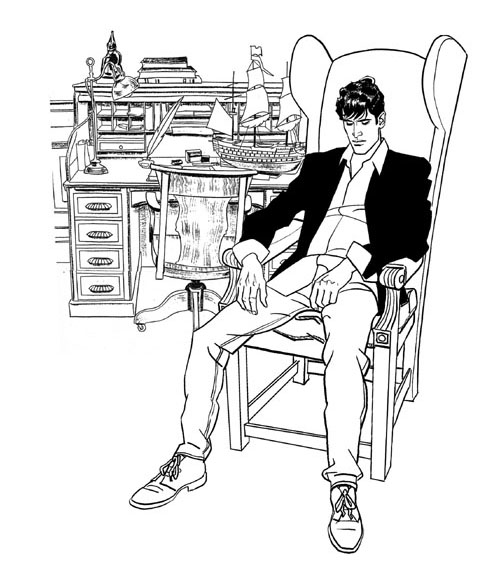

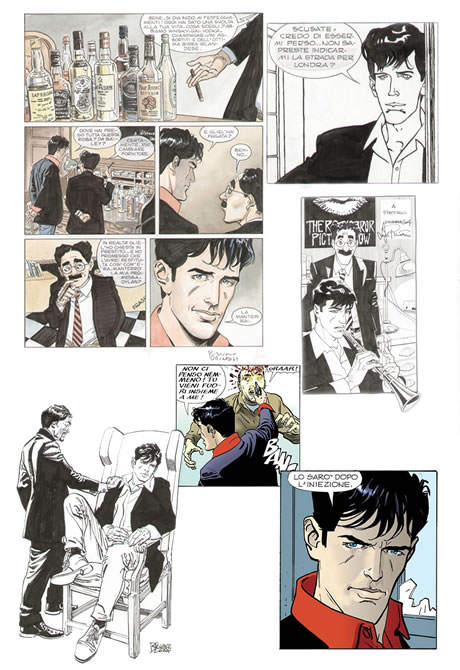

It follows the adventures of the perenially broke, self-proclaimed “nightmare investigator”, whose name, according to Sclavi, was equally inspired by the poet Dylan Thomas and the Italian title of a Mickey Spillane novel (Dog figlio di), and it’s exactly this equal-measured regard for both the highbrow and the lowbrow art that makes the series’ best moments so exciting and unpredictable. In a lot of ways, Dylan is the classic pulp hero: his dashing good looks modelled after the actor Rupert Everett, he usually wears the same, easily identifiable outfit consisting of jeans, red shirt, and a black jacket, lives at a very specific address in London (7 Craven Road, a reference to both Wes Craven and Sherlock Holmes, whose 221B Baker Street residence is prominently featured in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories), and drives an old Volkswagen beetle with the license plates “DYD 666”. And like Holmes, he’s got an unique assortment of habits and traits, of which the most prominent are his hopeless romanticism and the remarkable ease with which he falls in (and out of) love.

And he’s got a wise-cracking sidekick named Groucho, who may or may not actually be Groucho Marx.

In a lot of other ways, however, he is not a typical hero at all. He posseses no exceptional skills or smarts and is rather prone to failure. His neuroses and phobias are more reminiscent of Woody Allen, with whom he shares a penchant for the clarinet, than a pulp archetype, and he carries around psychological baggage of Greek proportions: most of the women he beds bear a resemblance to the enigmatic Morgana, who may or may not be his (un)dead mother, and his arch-nemesis is a doctor named Xabaras, who may or may not be be his Dad (and is perhaps the Devil himself). This particular brand or Oedipal necrophilia becomes more disturbing as the series unfolds and Dylan (and the reader) learns more about his forgotten childhood.

The early Dylan Dog stories are usually based on established, familiar concepts (zombies, werewolves, vampires, etc.), but Sclavi often manages to put a fresh spin on them (in true Italian tradition, this often includes gratuitous nudity and violence). References to film and literature abound, but he never lets the knowing wink turn into ironic detachment, let alone parody. He gleefully raids the history of pulp fiction, but unlike others who have made a career out of cultural cut-and-paste, he knows that is where his serial ultimately belongs, and he revels in it. Similar to the films of fellow Italian Dario Argento, Dylan Dog often manages to transcend genre boundaries, with its graphic gore and splatter seamlessly making way for poetic imagery and surrealism, but at the end of the day, there is a refreshing lack of pretense that this is anything other than pulp.

Unfortunately, Sclavi’s progressive lack of involvement in the production of the book during the mid-to-late 90s marked a significant, if inevitable, decline in quality, as writers Claudio Chiaverotti and Pasquale Ruju were left shouldering most of the burden of carrying on the highly successful franchise without its creator (who would later return only as an occasional guest writer), with wildly varying results. Currently, the series is up to issue 276, not counting numerous one-shots and specials, and the constantly changing lineup of writers and artists continues to make it a frustratingly hit-and-miss affair.

That is not to say that The Dylan Dog Case Files, which collects all seven Dylan Dog stories previously available in English, most of which are from the early Sclavi period, is uniformly great. One of the things lost in translation is Groucho, whose name has been changed to Felix for the American editions, and his mustache completely erased from the art, presumably due to legal issues with the Groucho Marx estate, and it effectively robs the book of some of its trademark absurdity. The new covers by Mike Mignola are nice, but they’re barely more than re-drawn versions of the original ones, and while they might help in moving a few extra copies off the store shelves, the best thing about them is probably the interesting comparisons they invite.

There are also a couple of unremarkable stories here, including the original first Dylan Dog issue from 1986, L’alba dei morti viventi, or Dawn of the Living Dead, which is necessary for introductory purposes, but which seems a bit quaint in today’s zombie-saturated market. Just like the Romero classics on which it riffs, it needs to be viewed in its proper context to fully appreciate (and remember, twenty years ago, there just weren’t any books like the Walking Dead around). What has withstood the test of time, however, is the moody artwork by Angelo Stano, the definitive Dylan Dog artist, in my opinion, whose work is more informed by the expressionist linework of painter Egon Schiele than the EC and Warren Comic stylings employed by his peers, and is still as creepy as ever.

But the good stuff is really good. First there is Memories from the Invisible World (or Memorie dall’invisible), which features a “slasher flick” type of plot narrated by a guy turned invisible because everyone stopped paying attention to him (and which was originally published as issue 19 in 1988, pre-dating that one Buffy episode by a decade).

Then there is Morgana, originally issue 25, published in 1988, and one of my favorite single comic books of all time. Thematically a sequel to Dawn of the Living Dead, this is where the series’ meta-fictional and post-modernist aspects completely take over, resulting in a surreal, self-referential romp, which features a cartoonist stand-in for Sclavi and Stano bemoaning a lack of readership for his comic in a world that is overrun by zombies (subtle!).

And if Morgana only recalls the works of Fellini, After Midnight (or Dopo mezzanotte, originally issue 26), is based directly on Martin Scorcese’s After Hours, and follows Dylan on a blood-drenched and highly whimsical journey through late-night London. These three stories alone make the collection worth buying, but the rest is always entertaining enough to make the entire book, despite its size and brick-like weight, impossible to put down.

For those left wanting more, there is also a movie starring Rupert Everett called Dellamorte Dellamore, based on a novel by Tiziano Sclavi, which itself is based on characters Sclavi introduced in the third Dylan Dog annual, Orrore Nero. Dellamorte Dellamore is a play on words, meaning Of Death Of Love (normally spelled della morte dell’amore, but changed here for obvious reasons), and is better known in the States as Cemetery Man. In it Everett plays Francesco Dellamorte, a cemetery caretaker whose true job is to keep the dead who are buried there, well, dead, and whose routine-filled existence begins to unravel when he falls in love with a mysterious stranger, played by the voluptuous Anna Falchi, in various states of undress (and undead).

Even with the serial numbers filed off, this is, for all intents and purposes, a Dylan Dog film. Directed by cult director Michele Soavi, former assistant to Dario Argento and Terry Gilliam, it is remarkably rich with atmosphere and beautiful visuals, with the right amounts of dark humor and existentialism thrown in, not to mention the usual Dylan Dog themes of death, love, and obsession, and Rupert Everett looking every bit like he had just leapt out of a comic page. Filmed in 1994, it is one of the last great Italian horror films, but like an above-average episode of the comic book that inspired it, it is also a lot more than that.

And then there is the “real” Dylan Dog movie, Dead of Night, which is currently in post-production and still looking for a release date. It features no involvement from Tiziano Sclavi, is rumored to be aiming for a PG-13 rating, and is set in America, starring Brandon Routh as Dylan (in his third comic book movie in as many years, presumably in a bid to eventually end up on every XXXL t-shirt in existence). He looks utterly unconvincing in the preview images I’ve seen so far, and it all reminds me too much of the Constantine fiasco from a few years back, so I’m keeping my expectations accordingly low. I wish it all the best, however, because getting more English language editions of the series likely hinges on the box office success of this film.

In the meantime, if any of this sounded even remotely interesting, you should check out the few things that are already available. You will dig them, I stake my robot reputation on it.