This first appeared on The Huffington Post.

Douglas Rushkoff is one of the world’s foremost expert, theorist, documentarian, and teacher about new media, popular culture, and the programming inherent in the mass media. He’s directed Frontline documentaries, written best-selling books about the topics, and has talked about it around the globe.

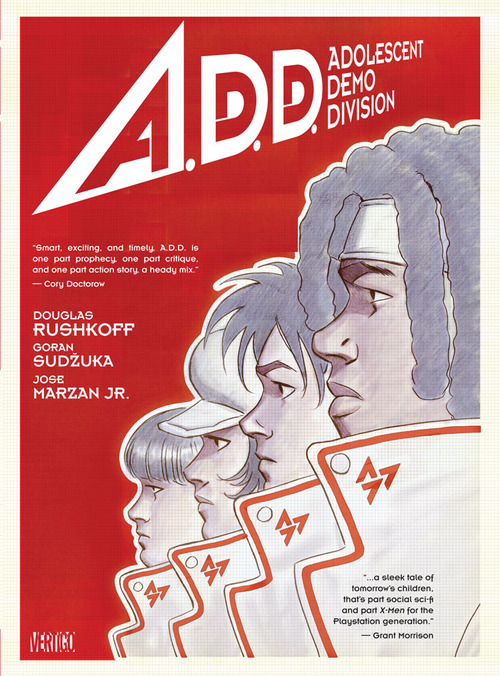

He’s set his sights once again on comics, and this time it’s with the upcoming Vertigo release A.D.D. It stands for Adolescent Demo Division, and tells the story of a lucky group of teenagers who get to do nothing but play video games all day. They’re rock stars, traveling around, playing against each other, as well as regular kids. But all isn’t as it seems. They’ve been raised since birth as test subjects so their corporate owners can determine the best way to market their messages to the kids of the world.

It’s a great read and a startling look at a reality that is already all around us. It works on every level, as a fascinating graphic novel, a biting social commentary, and a warning to get our act together.

A.D.D. is a clarion call for media literacy, but also an action-packed adventure story. With any luck, you’ll all be buying copies of the book and handing them off to your loved ones who happen to be gamers or readers of graphic novels and we can start down the long, cleansing road of de-programming the marketing in our culture.

I was able to talk to Rushkoff about the book and we had a fascinating conversation about the book and media literacy. Presented below are the highlights.

Bryan Young: How far off are we from living the events of A.D.D.?

Douglas Rushkoff: In some ways, it’s already worse than this. The whole trick in turning something from non-fiction to fiction seems to be less about predicting imaginary scenarios than it is about making the unseen reality visible. So really, what you need to do is come up with visual, identifiable characters and circumstances that depict what’s actually going on in a way that we can see it. What I’m trying to do is come up with characters and institutions that embody the causes and effects in modern mediated culture. The kinds of things that, say, Facebook is doing to teenagers today are not necessarily conscious acts of Mark Zuckerberg and they’re certainly not felt influences by the kids who are coming to them. It’s almost more a systemic influence that feeds that into itself, changing behaviours and then leading to new techniques that then change behaviours in other ways. All this kind of big, unconscious blob. And what I was trying to do was say, “What is a situation I can create where people can point to what’s happening.” What if someone was able to look at this whole systemic mess and see the intent? And who would it be that is most likely to do that? Who would be able to see through this media facade? For me that’s going to be kids with special disorders. It’s going to be kids who are able to see the system from a completely different perspective.

BY: What made you pursue this story specifically that made you want to do it in this medium? What brought you to a graphic novel for this message?

DR: In some ways this is the same story I’ve been telling through every medium that’s at my disposal. This is a story I was telling, in one way or another, in 1999 with “The Merchants of Cool”, trying to show kids MTV is this feedback loop where there are marketers watching them for what to put on the screen, that then kids watch and then imitate and then get watched again by marketers so that there’s this cultural feedback loop where there’s no conscious execution of art or strategy. It’s just a machine. It has an almost centrifugal force that pushes kids out to the extremes of behaviour — this mid-riff Britney Spears person, the male, mindless mook of the MTV Spring Break. I started telling it way back then and through all this other books. I’m doing the same thing. I’m deconstructing the corporate culture accelerated through media so that people can become more conscious. In this one, partly it was Karen Berger who runs Vertigo who came to me after Testament, which was kind of my labor-of-love theories about a futuristic bible retelling. She said, “Look, you’re this big media theorist guy, it would be a shame not to exploit that in something we do in Vertigo. Why don’t we let you do a piece that is what you would want to say to our audience about the media landscape today, what would you want them to know if you could tell them one thing?”

I thought about that long and hard and it seemed like the easiest way to encapsulate what I wanted to say to these kids (though for me at this point, kids is people 30 and under) is what if what if some of the things that are happening to us aren’t bugs but features? I said this way back when in a little red book called playing the future, but, what if Attention Deficit Disorder isn’t a bug, but a feature? What would that mean? It would mean that it’s not a sickness, but an adaptive strategy in a world where people are trying to program you every where you look. And that was something that I could say explicitly with a non-fiction book about kids and education and pathology that no one who I care about is actually going to read, or I can say it in a story that really turns that character, that adapting young adult, into the hero. I can create a narrative that this kid that the comics reader who is currently the target of billions of dollars of corporate manipulation every year, how can they see themselves as the hero in that scenario, rather than the victim? The way I did that in the story was creating the ideal life, which is basically getting to play a video game all day and show what the underlying problem of that is, and then create a heroic journey out of that. And what does out of that really mean? It turns out that it’s a little different than they expect.

BY: You’ve said this in other mediums, and to us in the documentary about obesity I produced, but we don’t teach kids media literacy, we don’t teach them how to watch TV, we don’t teach them how to use computers and video games, instead they are used by them. Since we don’t teach kids media literacy or critical thinking skills, are they going to be able to see the story and apply it to themselves?

DR: They’re living it. That’s the beauty of fiction compared to non-fiction, it is a story. It’s like going to Jesus and he’s saying, “There’s a person in the road and you come across him, what if that was me?” Are people going to get that? Are they going to understand that that means they need to be charitable? Well, yeah, they’re going to understand that it means to be charitable a lot more than just laying out the law. It’s a way to experience and externalize these things. The fact is, kids — people — don’t want to know how to theorize. It’s a great, abstract skill for a certain group of people. And maybe a quarter of the population likes to think in that abstract way and the other three quarters of the population really respond to narrative. They respond to stories. Look at how something like The Matrix communicated 80 years of post-Modernist thinking to a completely new generation who knew nothing about theory. It really can work. I don’t think this will have the impact of The Matrix, necessarily, but stories do communicate in a different way.

BY: I think one of the best things about A.D.D. is that it provokes these conversations about media and how we perceive it. The book was great, I absolutely loved it, but reading it I feel like there’s a better conversation to be had than patting you on the back about the story, you know what I mean? I think the book would do that for audiences, too, where they can read it and instead of talking about how fantastic the art was or specific story beats, it raises deeper issues and deeper conversations that that, which… was that the goal or the hope?

DR: Well, there’s a double-goal. The original editor and I decided early on that we wanted a very simple look and feel for the book. That was for two reasons: one was to make it really accessible to a young adult audience, but also so that the ideas of the story would be able to come out and hover above the surface, so they wouldn’t get stuck in these over-the-top impressionistic scenes. We kept the plot and the characters really clean so that the ideas which might otherwise seem complex didn’t get buried in there. We didn’t want this to get mistaken for Ross or American Horror Story or something that’s so complex and convoluted that you’d miss the themes.

Rushkoff and crew certainly hit their mark, creating an eye-opening story with clean art and a deep, challenging story that holds you and keeps you reading.

A.D.D. hits shelves on January 31, 2012 and I hope you’ll pick up a copy and pass it around to those around you most in need of a good story and a desire to learn more about their media landscape.

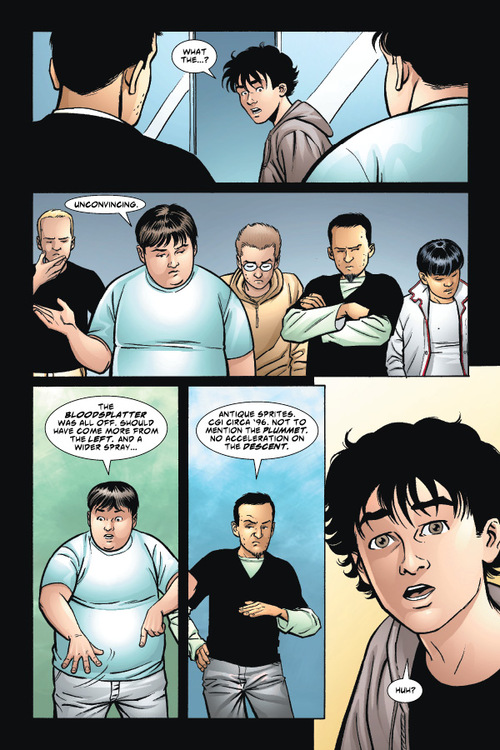

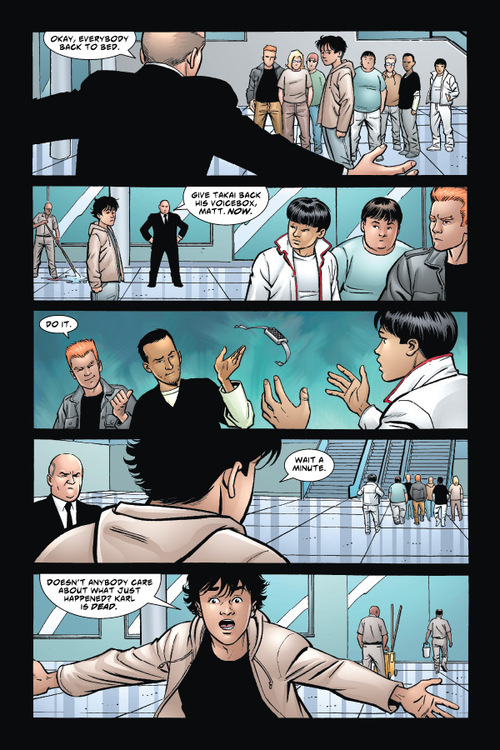

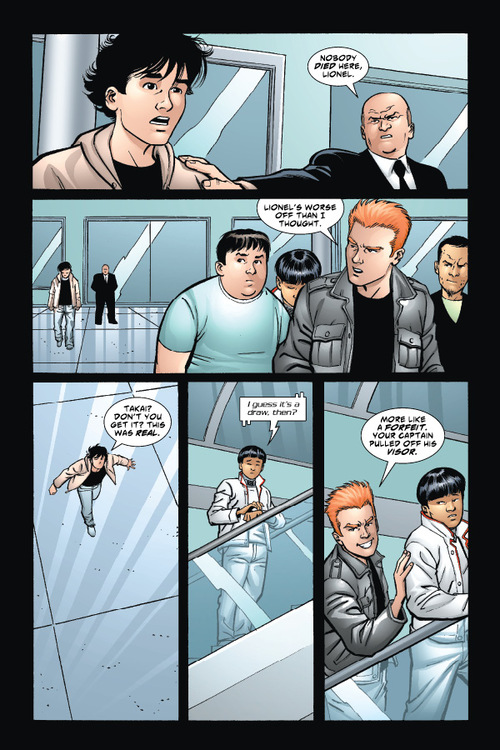

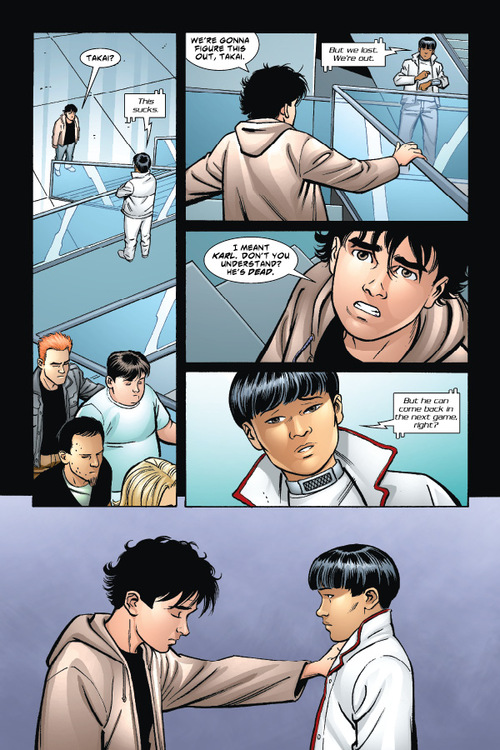

Included below is an exclusive 5 page preview of A.D.D. for readers of this site:

Bryan Young is the editor in chief of Big Shiny Robot! and the author of Lost at the Con and God Bless You, Mr. Vonnegut.