There are entire fields of study involving the investigation and understanding of language. Linguistics and philology suss out the origin, evolution, and usage of words in both historical and modern contexts. In most cases it is possible to take any given word, commonly accepted or newly adopted slang, and trace it back, sometimes thousands of years or more.

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2012 suggests a set of 23 words believed to date back in more or less their current form at least 15,000 years. However, sometimes words come out of nowhere, either necessitated by the emergence of some new thing in need of naming, the mashing up of existing words, or the brilliantly nonsensical minds of artists, writers, and entertainers.

It’s fairly common knowledge that Shakespeare was responsible for the coining of many words in common use today. In fact, Shakespeare is credited with creating more than 1700 words through myriad techniques, mostly by modifying existing words in some way or mashing words together into a portmanteau (fun fact, ‘portmanteau’ in this context is itself an invented word, first used by Lewis Carroll in Through the Looking-Glass).

Well, slithy means lithe and slimy. Lithe is the same as active. You see it’s like a portmanteau, there are two meanings packed up into one word. -Humpty Dumpty, explaining Jabberwocky

It might be a reasonable supposition that in the world of language there is nothing new under the sun. If a word is needed, surely it has been coined by now, right? Not so. This business of inventing new words is still going strong and we’re not just talking about the constantly evolving slang of modern youth. So buckle up fam cause this sh*t is lit(erary).

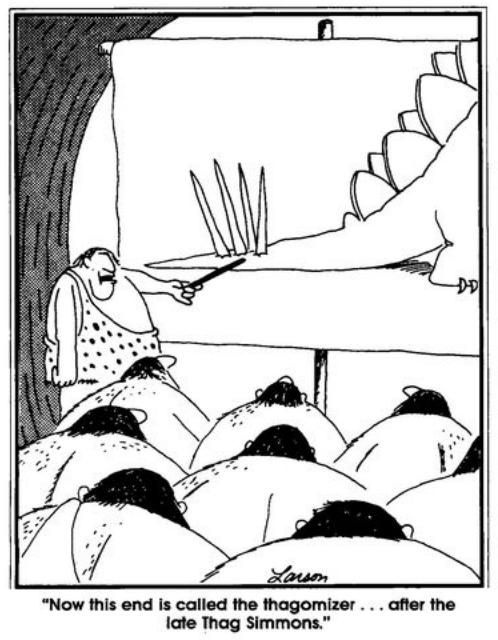

Thagomizer

Raise your hand if you like dinosaurs. Now, raise your other hand and give yourself a high-five because dinosaurs rule. Any branch of scientific inquiry that causes toddlers the world over to learn the official taxonomic names of things is objectively rad. If you’re like me, it’s been at least twenty years (maybe more, but don’t ask, it’s rude) since you learned the names of all your favorite dinos but you still remember them, don’t you? You’ve got your T-Rex, Raptors, Triceratops, Stegosaurus… but answer me this, what do you call the group of spikes at the end of a Stego’s tail? If you don’t know, then bask in the awesomeness of my superior intellect you ignorant toddler. If you do know, congratulations on reading the heading of this paragraph. You’ve mastered the art of foreshadowing and reading comprehension.

While evolution has brought us ‘endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful’ (and at least a few most horrible and most why-do-you-exist-ible, seriously check out this nasty bugger) it isn’t great at breaking the mold. Most things, human beings included, are just remixes of familiar old biological tunes. As such, there aren’t many opportunities for paleontologists to name new stuff. Which makes it all the more shocking that nobody thought to give that bunch of spikes at the end of a Stego’s tail a cool name. That is, until 1982 when Gary Larsen came along and slapped his name on those bad boys.

One year later, the term was picked up by Paleontologist Ken Carpenter who used it to describe a fossil at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and the rest, as they say, is pre-history. While the term is informal, it has been adopted by a little museum called the Smithsonian (among others). You may have heard of it. And thus, Gary Larsen entered the hallowed halls of taxonomic legend, just like the late-great Thag Simmons.

Nerd

If you’re a regular visitor to Big Shiny Robot you’re already familiar with this word, you probably hear it in your dreams before you wake in a cold sweat and thank whatever god keeps you from existential terror that high school is over. You may also be familiar with this word if you’re a human being living in the twenty-first century. What you may not know is where the word originated.

It wasn’t always a slur thrown at all the most interesting people I know or the the name of a criminally underrated crunchy candy. Once upon a time it was just some nonsense thrust from the magical mind of one Theodore Geisel, you may know him by his pseudonym, Dr. Seuss.

In his book If I Ran the Zoo, Seuss invented a slew of characters and creatures as he was wont to do. Among them, was the noble nerd, clad in a black t-shirt, hair disheveled, and red in the face. It’s not difficult to understand why the term took root, what is a mystery is why none of the other invented words that share the page with the noble nerd enjoyed similar legacies.

Perhaps it’s one of those bizarre cultural memes we’ll never fully understand. Speaking of memes…

Meme

Memes are like pop songs. First you don’t get what all the commotion is about, then you jump on the train, then they get beaten into you until you feel irrational anger whenever you encounter it. Seriously, the next person I hear say ‘Howbow Dah’ is going to have to Cash me Ousside.

But before they were image macros crowding up your social media feeds, ‘meme’ was coined by Richard Dawkins as a way to describe ideas or behaviors that spread from person to person within a culture. You probably know Dawkins for his outspoken and unabashed atheism, he shows up anytime Ken Ham or Kirk Cameron badly photoshop a duck’s head on a crocodile or build a creation museum. But Dawkins is actually a renowned evolutionary biologist, before he was the poster boy for the non-religious he wrote a book called The Selfish Gene which explores the propagation of genes, expanding on natural selection.

In the book, Dawkins explains how ideas and behaviors can spread through a society in the same way that genetic mutations can spread through a species. This idea wasn’t new to Dawkins, it was discussed during Darwin’s time. T.H. Huxley, a contemporary of Darwin’s described this phenomenon thusly: ‘The struggle for existence holds as much in the intellectual as in the physical world. A theory is a species of thinking, and its right to exist is coextensive with its power of resisting extinction by its rivals.’

Dawkins based the term on a shortened version of the word mimeme, Greek for ‘imitated thing.’ While memes in their current form have existed as long as the internet, and the term and study (memetics) of them has existed since shortly after Dawkin’s writing, memes themselves have existed probably as long as human beings have been sharing ideas.

Those of you who remember a time before the internet, probably remember seeing ‘Frodo Lives’ emblazoned on buttons, stickers, and bathroom walls next to phone numbers promising good times. There was also that pointy S that every kid has drawn in school since no one knows when. Perhaps the oldest known meme is the Sator Square, a two dimensional palendrome that can be read from any side and translates roughly to ‘the farmer works a plow.’ It’s good to know that modern culture doesn’t have a monopoly on nonsense memes. Howbow dah.

Robot (Robotnik)

I would be remiss if this invented word list didn’t include the word that makes the crux of our namesake. While we’re still waiting impatiently for robot butlers, robot best friends, and robot uprisings, robots have cemented themselves as a part of our world. You can get a robot alarm clock, a robot vacuum, even a robot that will fold your laundry (finally).

Robots are so ubiquitous it’s surprising that the concept of a robot is so new, relatively speaking. The term first appeared in a play by Czech playwrite Karel Čapek titled R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) about a factory that makes artificial people void of emotion but capable of doing all of the work human beings didn’t want to do.

In the play, the robots eventually rise up and overthrow the human beings who have become so lazy they can no longer sustain themselves without the help of their artificial slaves. Čapek needed to invent a name for his creations, originally opting for Labori but later abandoning it. It was his brother Josef who suggested using robot (or robotnik in Czech) which means ‘forced worker.’

Given the landscape of the time with the rise of communism and fascism, Čapek’s play can easily be seen for what it most certainly was, a thinly veiled allegory about the greed of the upper class at the expense of the lower. The end of the play, with their masters overthrown and the world built anew by the robots, is a clear message to the world leaders of the time. Which is probably why Čapek was on Hitler’s short list, right up until 1938 when he died of the flu.

Later Isaac Asimov coined the term ‘robotics,’ a derivation of Čapek’s creation with his Three Laws of Robotics. These laws define the limitations of a robot in preserving its own existence as well as the safety of the human beings around it. Though, anyone who has read Asimov’s work knows those laws rarely hold as steady as one would hope.

So you might want to think twice the next time you kick your Roomba across the room for smearing dog crap across the carpet.

Gremlin

The concept of mythical creatures causing trouble and making mischief for their human counterparts is nothing new to folklore. Stories of trolls and gnomes date back to antiquity and have roots in various mythologies the world over. However, Gremlins are relatively new to the scene. The word is thought to be a mashup of ‘goblin’ and the Old English ‘gremman’ which means to anger or vex.

Gremlins date back to Royal Air Force pilots circa World War I, who blamed small, nefarious creatures for the failures of aircraft. While in some circles these stories may have been thinly veiled attempts to blame aircraft failures on something mystical rather than on fellow soldiers, there were pilots who maintained they had in fact seen creatures chewing on wires and otherwise sabotaging planes on the ground and in the air.

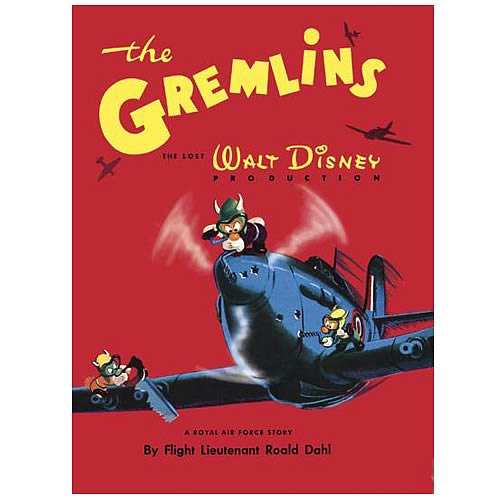

Gremlins first appeared in print in a poem published in the journal Aeroplane on 10 April 1929. Author Roald Dahl is credited with popularizing Gremlins and introducing them to the world at large. Dahl himself was an RAF pilot, so he would have been familiar with the stories. He experienced his own accidental crash landing, however this was due to an inability to see the landing strip before running out of fuel, not the machinations of ill-tempered sprites.

Dah’s first children’s book was titled The Gremlins which he wrote for Walt Disney Productions. The story was meant to be made into an animated feature. Characters were designed but the project was scrapped before completion. While the Disney film never saw the light of day, Dahl’s creatures did eventually make it to the big and small screens.

The Twilight Zone episode Nightmare at 20,000 Feet specifically tells the tale of a gremlin sabotaging an aircraft, a direct reference to the stories of wartime RAF pilots. Steven Spielberg’s 1984 film Gremlins bears the name of the creatures, while the production publicly distanced itself from the previous, abandoned iteration, there’s no arguing that the movie never would have happened without Dahl’s earlier publication.

It turns out, even after all this time, language is still evolving. Maybe don’t give the kids in your life too much hassle when they say things that sound ridiculous, they may just be ahead of their time.