“For nearly forty years this story has given faithful service to the Young in Heart: and Time has been powerless to put its kindly philosophy out of fashion. To those of you who have been faithful to it in return… and to the Young in Heart… we dedicate this picture."

These are the words with which MGM’s seminal classic The Wizard of Oz introduced itself to audiences in 1939, in the form of an opening title card. Upon first glance, this may seem like little more than an endearing curiosity. But when contextualized and placed alongside the films which preceded it, the title card’s true purpose is revealed: it’s an earnest plea for audiences to find it within themselves to suspend their disbelief.

Despite the success of musicals on the stage dating back literal centuries, the musical as a cinematic spectacle had a far more tumultuous beginning. Following The Jazz Singer’s release in 1927 and the advent of proper sound in film, musicals became all the rage in Hollywood. Yet, while one might have expected to see a string of fantastical, traditional musicals meant to cheer audiences up in the midst of the Great Depression, this was not the case. Though there were incredible musical films released throughout the late 1930s, such as 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, and Footlight Parade, all of these works were ‘backstage musicals’: films about onstage musicals, using the narrative as a built-in excuse for the musical numbers themselves, just like The Jazz Singer. It was feared that audiences would balk at the notion of a full-blown, earnest musical, so every film was constructed with a narrative explanation for the spectacle, to assuage these concerns.

Until Walt Disney came along.

Disney had been making musical animated shorts for quite a while, with the likes of his Silly Symphonies, but the 1937 release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves changed everything. Not only was it Disney’s first feature film and the first animated feature film in general, but it was also a landmark for musical cinema: a genuine, non-‘backstage musical’ musical film. Entirely devoid of any kind of narrative reasoning for its musical numbers, Snow White had more in common with the works of the stage than it did with any prior musical films, embracing overt fantasy in every way. The film was a gargantuan success, making Disney a household name and putting the thought into the rest of Hollywood’s mind that maybe, just maybe, audiences could be talked into buying into a live-action musical without the narrative crutch.

Which is how we get to Mervyn LeRoy’s production of The Wizard of Oz two years later in 1939, foregoing any kind of excuses and delivering a true-blue musical amidst an incredibly troubled production. After having multiple actors drop out at the last minute, going through several changes of directors, and the studio getting such cold feet that they very nearly cut “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from the film entirely, it’s no real surprise that LeRoy had a title card added to the start of the film just prior to release that practically begged audiences to buy into his big gamble and believe in the fantastical.

But it paid off in spades. The Wizard of Oz was and remains a massive success, one of the most iconic films of all time for generations of moviegoers, and a work that inspired decades-upon-decades of subsequent movie musicals. It turns out that what the audiences of the Great Depression really wanted, really needed some might say, were films bold enough to break through the jaded cynicism of their day-to-day reality and genuinely affect them.

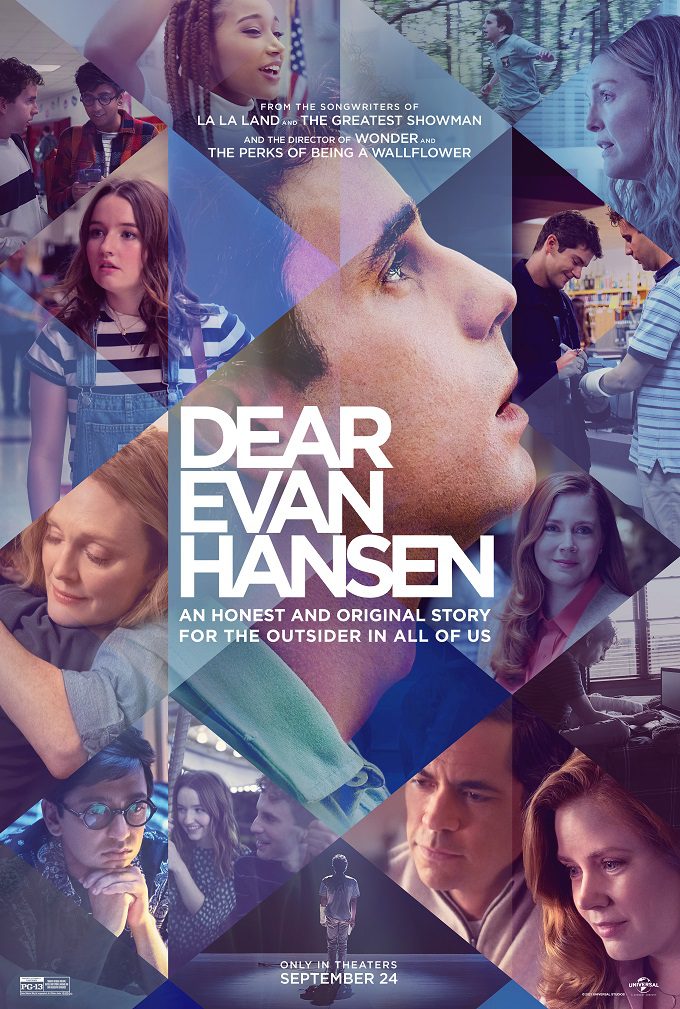

Dear Evan Hansen is a 2021 film adaptation of the wildly successful, Tony-award-winning stage play. The film is being released in the midst of the still-raging COVID-19 pandemic to audiences who, it’s fairly safe to say, have a bit of their own jaded cynicism in their day-to-day lives. And while the film may be a fairly faithful narrative translation of the literal text of the source material, it entirely amputates the subtext and visual craftsmanship of the stage play, in favor of toning everything down and making it (as the cast and crew have stressed repeatedly on the press tour for the past several months) as “grounded” and “real” as possible.

Admittedly, the story of Dear Evan Hansen is a bit of a hard pill to swallow. Steven Levenson’s script tells the story of Evan Hansen, an isolated and lonely high school boy who gets mistaken for a close confidant of a fellow classmate who recently committed suicide and finds himself the center of attention for the first time in his life. Evan repeatedly declines to come clean about the fact that he hardly even knew this classmate, instead opting to use the deceit to grow closer to the classmate’s family, including starting a relationship with said classmate’s sister. Eventually, things spiral out of control, social media spreads Evan’s lies and clout even further, and Evan is forced to come clean. Everybody learns a lesson, etc. and so forth.

That’s a troubled protagonist, for sure, and a hard arc to sell. But what’s important to stress here is how the subtext apparent in the craft of the stage play works to contextualize the story. The entirety of the stage play is driven by the innovative stage design, which features multiple screens and projections, able to bring the sprawling, intimidating vastness of the internet and social media to the stage. Evan’s loneliness is felt all the deeper specifically because it is framed against this backdrop of a constantly intertwining web of connections, a backdrop that only accentuates his anxieties and fears of not being accepted. Crucially, Evan’s big ‘I want’ song, “Waving Through a Window”, is quite literally about his screens, the way he interacts with his peers via the online world. He is “on the outside, always looking in”, retaining his status as an observer with a front-row seat to the lives of his peers but never being an active participant. During the first-act-closer, “You Will Be Found”, Evan’s big speech about his deceased classmate goes viral on social media; here, he has stepped into the spotlight and it has garnered him acclaim. Suddenly, the sprawling online universe on-stage is hyper-focused on Evan. He is no longer an observer but rather the central star of this world that he once only viewed from a distance. Time and time again throughout the show, Evan’s descending arc is underscored by the presence or lack of his interactions with this digital world that literally encompasses him.

This isn’t just some gimmicky stage design for the sake of grabbing the audience’s attention, it’s a core pillar of the work that is in active conversation with the text. In the world of Dear Evan Hansen, the internet, and even more specifically social media, is performance. These are platforms that have, in their own unique way, turned everyone into storytellers.

Thus, for the film adaptation of the play to not just shy away from these elements, but to flat out exorcise them all together is a detrimental choice. Whereas on stage the looming presence of social media, its ever-watching eyes and its far-reaching grasp, was sewn into the very fabric of the visual work, the film has little-to-no interest whatsoever in visually exploring the online world outside of a handful of cutaway shots or inserts. Where the source material pretty blatantly played up the inherent subtext of “Waving Through a Window”, the film’s take on the song opts to not feature a single visual cue to social media and instead quite literally frames Evan to be looking through a window for an entire chorus. This is a great encapsulation of what this larger stylistic choice, to rid the work of one of its defining aspects in translation, has done to Dear Evan Hansen. The film feels blissfully ignorant of the meaning of its source material at best (waving through a literal window) and downright malicious at worst (cutting all of the songs the grieving parents get to relay their honest emotional experience, in favor of keeping all of Evan’s). Which is strange, given just how many of the original creators and stars are involved with the film.

Sadly, this reluctance to embrace any kind of visual innovation or anything outside of the distinctly made-for-television visual stylings the film has, carries over into the musical setpieces as well. The stage play is an intimate work, but it’s full of wonderful choreography and staging that accentuates the music through movement, generating a genuinely moving sense of synchrony between the music and visuals. The film’s musical numbers are almost entirely devoid of movement, largely constructed in the edit through what feels like shot-for-coverage execution that is not even attempting to accentuate the music but instead opting to idly coast upon its momentum. Dear Evan Hansen is a film that not only seems ashamed to be a film adaptation of its musical source material, but it’s also a film that seems ashamed to be a musical at all.

And this is emblematic of a larger issue: we’ve somehow slid back into the mindset of the 1930s.

Modern musical films are constantly apologizing in one way or another for being musicals, whether that be through fundamentally altering the structure of source material out of fear that it won’t fit the medium, building in-narrative justifications into the work so as to formally excuse the musical aspects, or presenting the entire thing with a grating sense of ‘can you believe how goofy this is? A musical!?!’ winking-at-the-audience cynicism. Or there’s my personal favorite trick of the bunch, which we’ll affectionately call ‘The Tom Hooper’, wherein one takes the musical, regardless of form or content, so seriously that the final product is inseparable from buzzword descriptors such as “grounded” or “realistic”.

How did we get here? Well, there are certainly some uncomfortable parallels between the Great Depression and the various crises that our nation has gone through in the past two decades or so. And the rise of online culture over those same twenty years as the internet has evolved from a weird little gathering of misfits to a never-ending supply of listicles and ‘Ending Explained’ YouTube videos, all in the name of benefitting ever-growing companies chasing SEO-fueled money, certainly hasn’t helped, leaving in its wake an entire generation of audience-members who think the point of watching a film is to perpetually and pedantically outsmart it on a narrative level and never even begin to engage with it on an emotional or thematic level. So there’s this palpable reluctance from major motion pictures to be, for lack of a better summation of it, earnest. For films at large, yes, but for musicals especially.

Which is a damn shame, because musicals are beautiful. It’s a genre that so wonderfully lends itself to the cinema, taking advantage of every single facet of the form and making them take flight. Seeing a great musical film is like witnessing an engine roar to life, firing on all cylinders and generating an entrancing full-bodied harmony that you didn’t know was possible until you witnessed it. Singin’ in the Rain, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Mary Poppins, West Side Story, All That Jazz, Little Shop of Horrors, Beauty and the Beast. These are remarkable cinematic works that are unparalleled in the depth of their resonance specifically because they are earnest works of art that take full advantage of the opportunities afforded to them by the musical form and do not shy away from them, feel the need to explain it, or apologize for it.

The film that kept creeping into my mind while watching Dear Evan Hansen was the theatrical musical release that immediately preceded it: Leos Carax’s Annette. Dear Evan Hansen is an entirely vanilla production, a watered-down iteration of its source material that actively dilutes itself and mutilates its form in the hopes of appealing to the widest possible audience. It hopes to not isolate a single soul by not making a single bold choice. Annette is a wondrously unhinged, idiosyncratic work of visual splendor in which there is hardly a single line of unsung dialogue, and which never even for a moment has an ounce of shame about being the most bombastic and extravagant musical film of the last decade.

We need more films like Annette.