Cinematic mastermind Alfred Hitchcock once famously weighed the value of surprise and suspense in film as follows;

“There is a distinct difference between ‘suspense’ and ‘surprise’, and yet many pictures continually confuse the two. I’ll explain what I mean. We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let’s suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, “Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence.

Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!”

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed.”

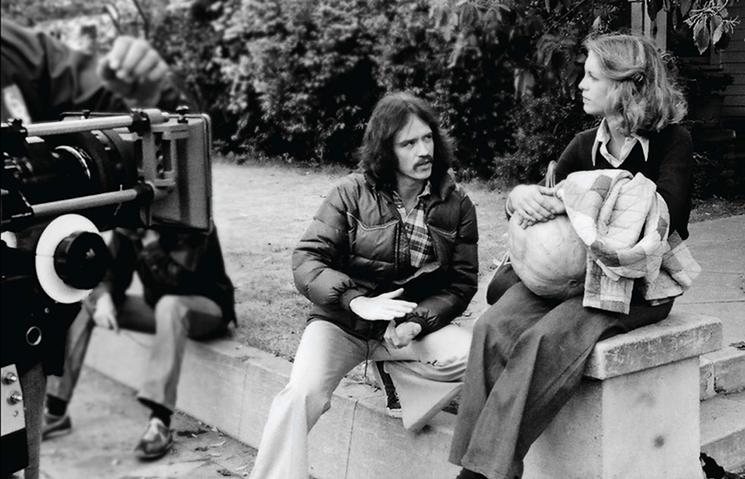

In the world of filmmaking, information is key. But perhaps in no other genre is it as crucial to eliciting proper reactions as it is in horror. Hitchcock knew this well; it is no accident that he was commonly referred to as the ‘master of suspense’. His ability to control and manipulate the information being given to the audience was unparalleled. In taking Hitchcock’s methods and craft to heart, one young filmmaker was able to craft a film forty years ago that remains one of the most suspenseful things ever committed to film, to this day. Like a masterful composer, Carpenter orchestrates sequences of suspense in Halloween like a layered and harmonic symphony, achieving a ‘fuller sound’ for his suspense that had a revolutionary impact on horror cinema.

To better analyze Carpenter’s technique, let’s take a look at one sequence in particular; Annie’s death.

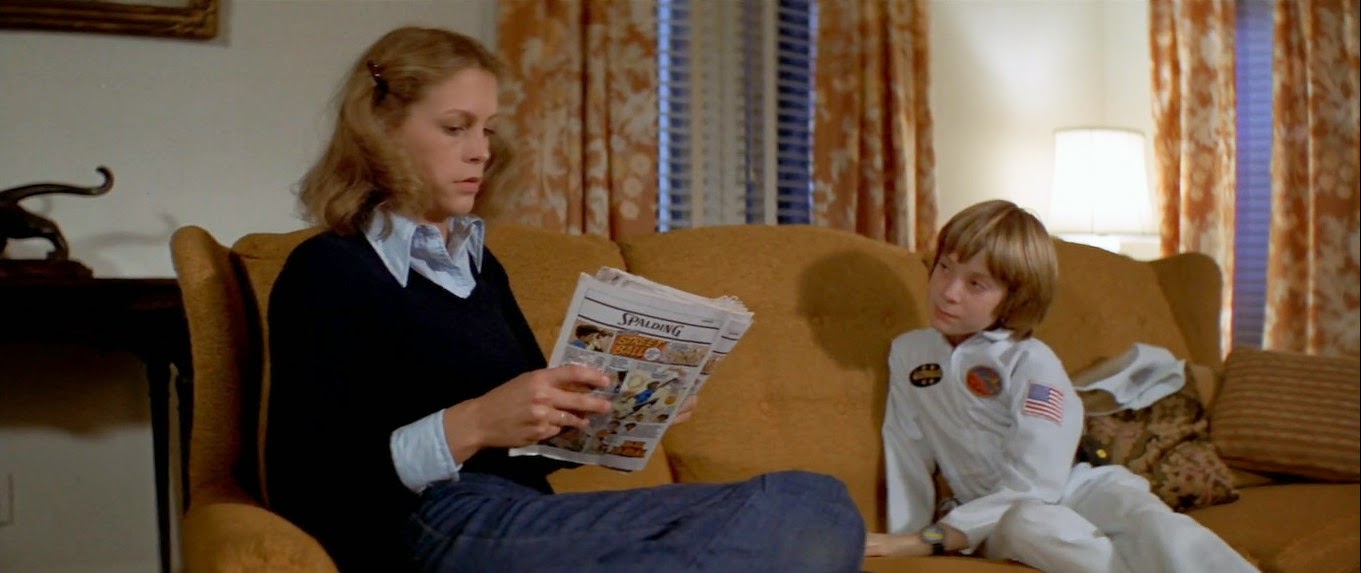

The first thing Carpenter does is establish the geography of the sequence. Annie Bracket is babysitting Lindsey Wallace in the Wallace house and Laurie Strode is babysitting Tommy Doyle in the Doyle house, directly across the street. This is established as Carpenter cuts back and forth between Annie and Laurie talking on the phone and ultimately gives the audience a firm sense of placement.

Which is when the first tremor of suspense sneaks in. As Annie is on the phone, Lester, the Wallace family dog, comes into the room with her and begins barking riotously at the back screen door. Annie discounts it as little more than an annoyance and initially, so too does the audience. The focus of this scene up until now has been on Annie and Laurie’s conversation and it squarely remains there, but a vague sense of dread begins to permeate as Carpenter allows Lester’s barking to continue. Which is when he capitalizes on it, cutting to an exterior shot of the Wallace house, where the audience sees Michael Myers standing outside looking in through the window.

This is the exact kind of information that Hitchcock states suspense revolves around. Here, Carpenter is giving the audience information that the characters in the narrative do not have. Michael becomes the ‘bomb’ from Hitchcock’s example, an element the audience now knows is present but that the characters are blissfully unaware of.

As Lester continues to bark, Annie calls for Lindsey to get him out of the kitchen. The film cuts to Lindsey, who is watching the television, not even acknowledging Annie’s voice. This raises the stakes, showing that Lindsey and Annie are isolated from one another within the house. Carpenter then takes us back to Michael outside, showing him stepping away from the window. As he does so, Lester stops barking and runs outside after him.

Again, Annie writes it off as nothing and continues talking to Laurie but the audience is acutely aware that this conversation isn’t the focus anymore. As they speak about Annie setting Laurie up with Ben Tramer as a date for the Homecoming dance, Carpenter’s looming camera takes us to the Doyle house. In one of Carpenter and cinematographer Dean Cundey’s uses of the iconic Panaglide camera, they literally minimize Laurie and the conversation in the background of the shot as Tommy Doyle wanders over to the window. He looks outside to see the silhouette of Michael Myers, the ‘boogieman’ as he refers to him, standing outside of the Wallace house across the street.

This builds suspense in a different way, a harmony to the events taking place at the Wallace house, if you will. Tommy becomes the in-narrative surrogate for the viewer, the only character who has the same information we do. The suspense revolving around him becomes whether or not he’ll be able to do anything about it.

He runs to tell Laurie, trying to get her focus off of the phone call and on to the real matter at hand, telling her “the boogieman’s outside!”. Yet when he and Laurie look out the window together, Michael’s silhouette is gone. Laurie resumes her conversation, fading into the unfocused background of the shot once again as the camera’s literal focus is kept on Tommy as he looks back out the window, searching for the boogieman. This tightens the screws on the tension of the sequence, as Tommy’s information is discounted and seen as invalid by Laurie, the primary protagonist here, putting her in complete juxtaposition with the audience who knows the information is all-too valid.

Carpenter then takes us back to the Wallace household, this time in a shot directly outside of the back door, watching Annie through the glass. This shot in-and-of-itself builds suspense, as it begins with only the sound of Michael’s breathing getting heavier off-screen until he steps into frame to watch Annie as she talks on the phone and makes popcorn. This escalates the suspense even further, as Michael literally closes in on his victim.

Annie then accidentally spills butter on herself, with the next shot placing us inside the house with her once again as she hangs up on Laurie. The dread escalates even further here, as now we can’t see Michael. Whereas the previous shot saw Carpenter making us voyeurs alongside Michael, this shot puts us firmly with Annie, facing the opposite direction of the back door. As Annie strips off her stained clothes, she’s more vulnerable than ever. Lindsey continues to be unresponsive to her cries for help and Annie’s just hung up on Laurie, leaving her completely and totally isolated. Even the physical act of disrobing leaves her incredibly vulnerable, so as Carpenter cuts back to the exterior shot of Michael watching, it feels as if all is lost.

And in a lesser film, this would be it. The film would capitalize on this high tension mark and have Michael swoop in for the kill. But Carpenter opts for something much more interesting. Instead, he actively de-escalates the tension. Michael accidentally knocks over a pot outside, leading to Annie looking his direction and Michael having to retreat. And sure, we see Michael ruthlessly murder Lester at this point but that’s to build suspense for the notion that danger still lurks outside in the darkness. It isn’t so much an accent to the sequence as it is a low rumbling note, a foreboding tone of the danger to come.

The sequence then cuts back to the Doyle house, where Tommy and Laurie are watching television as Tommy tries to convince Laurie he saw the boogieman. But Laurie actively soothes Tommy’s fears, meaning that even the audience’s in-narrative surrogate is calmed down. It’s a moment that feels remarkably like relief, which makes the juxtaposition of it and the moment that immediately follows it so effective.

From here, Carpenter cuts to Annie going out into the backyard of the Wallace house. She’s going out into the darkness, which we know isn’t safe, and the suspense and tension immediately begin to crescendo once again. She goes out into the laundry room to clean her stained clothes, where Carpenter then shows us Michael watching her through the laundry room door. Crucially, this shot is not over Michael’s shoulder or putting the audience with him. Instead, it’s a head-on shot of Michael, putting the audience with Annie. Whereas we the audience were forced into his voyeurism before, we are now squarely in the middle of the danger with Annie.

Annie hears a noise and fully opens the laundry room door, though when she does, Michael is nowhere to be seen. She brushes it off as nothing, leading to one of the most haunting shots in the entire sequence as Carpenter and Cundey keep the camera squarely locked on Annie doing laundry and the cracked open door next to her. The audience knows what lurks outside, even if Annie doesn’t, and leaving the door cracked forces the viewer to continually search that side of the frame for what might be out there in the darkness. Then the door shuts.

Annie attempts to open it but finds herself locked in. She calls out for Lindsey to come and help her but Lindsey is just as unresponsive as ever. Carpenter then cuts back to a head-on shot of Annie, in which we see Michael staring in at her through the back window. The next shot sees Annie turning around to look at the now off-screen back window and for a brief moment, we think she’s spotted him. But then it gets oh-so-much worse. Michael is no longer there but Annie proceeds to attempt to climb out of that very window. Here, the tension has been raised to a new breaking point and again, it feels as if the end must be near for Annie. But again, Carpenter actively de-escalates.

The phone rings and Lindsey finally picks it up to discover it is Paul, Annie’s boyfriend, leading to Linsey running out to the laundry room to get Annie. She discovers her stuck in the window and helps get her out, as Carpenter injects some disarming humor into the mix. They go back inside and Annie talks to Paul on the phone. Here, in yet another head-on shot that places us firmly in danger with Annie, Michael is seen looking in on her through the back door once again. But by the time she turns around, he’s gone. Much like Lester’ death, this moment serves as a low rumbling tone, a signifier that all is still very far from well.

Annie proceeds to take Lindsey across the street to the Doyle house so that Laurie can watch her while she goes to meet Paul. As they walk across the street, Carpenter shows us Michael watching them all the while, beginning the sequence’s third crescendo in earnest. Once Annie is in the Doyle house, Carpenter takes his time. Laurie and Annie talk some more about Ben Tramer and the homecoming dance, with shots of the windows and darkness outside constantly looming between them. Again, their focus is on the conversation but the film’s and the audience’s focus is on something much more dire.

Annie walks returns to the Wallace house where she attempts to open her car, only to realize that she doesn’t have her keys. Carpenter explicitly goes to a rarely-used close-up shot for this to hammer home the point that the car door is locked. The next several shots show her walking back around the house and through all of the places we’ve seen Michael throughout this sequence: by the laundry room, through the back door, around he side window of the house. It pays off all of the set-up of the sequence’s geography, as Carpenter physically places Annie in literal danger zones. To juxtapose this and heighten the suspense even more, Annie is at her most unaware here. She’s joyfully singing and whistling to herself, enamored with the notion of meeting Paul.

When she returns to the car with her keys, Carpenter cuts back to the close-up of the door handle as it opens without her ever having to unlock it. Suddenly, the tension is at an all-time high and the suspense is unbearable. We, the audience, know that someone is in the car. Annie does not.

Thus, as she gets in and sees that all the windows are fogged up and begins to notice something is amiss, the audience is doomed to squirming in their seats, knowing what must be coming. And then, it finally does. Carpenter capitalizes on a full fifteen minutes of suspense as Michael suddenly lunges from the back seat to strangle Annie to death.

This sequence is not alone, as the entirety of Halloween is a masterclass in how to create suspense. It is such an effective and horrifying film because of the way Carpenter utilized and revolutionized suspense. Each beat plays like an individual note, each shot like a motif, all of it adding up to create some of the most nail-biting sequences of suspense in film history. He regularly pushes the suspense of a sequence and his audience to the breaking point, only to keep them waiting.

It’s a masterful use of the form that perfectly understands the value of fifteen minutes of suspense versus fifteen seconds of surprise.